The first V 17 10

produced 750 hp. By the beginning of World War 11

it was producing 1050 hp, then 1125, then 1325,

and late model P‑38's got 1475. But engineers

recognized that there was a lot of energy going

out the exhaust pipes.

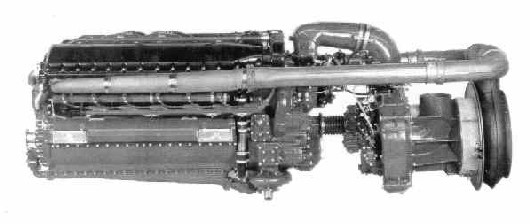

An attempt to

recover some of this energy resulted in the

turbo-compound V1710 shown at the bottom of the

page. It was identified as the V1710‑E22 by

Allison, and as the V1710‑127 by the government. A

turbo-compound engine collects all of the exhaust

gasses and runs them through a turbine, with all

of the power generated going back into the

crankshaft and ultimately to the propeller. It

differs from a turbo-supercharged engine, which

uses exhaust gas energy to increase the pressure

of incoming air. Work on this engine began in

about 1944 and continued until 1946, when Allison

asked that it be cancelled because turbine engines

had greater promise. It was the first successful

turbo-compound engine, and probably one of only

three to ever be built. This engine was designed

to power the XP63H, which, as it turned out, never

flew. The V1710‑E22 had a military rating of 2320

hp, and a War Emergency Rating with water/alcohol

injection of 3090 hp.

The most successful

turbo-compound engine was a version of the

air‑cooled, 18‑cylinder, two‑row radial Curtiss

Wright R3350. This engine had three turbines, each

fed by 6 cylinders, that were geared to the

crankshaft. The normal version produced 2700 hp

and weighed 2850 lbs. The turbo-compounded version

produced 3500 hp and weighted 3440 lb. This engine

was used on the Douglas DC‑7 and some versions of

the Lockheed Constellation. The other

turbo-compound engine is the Napier Nomad, which

was built in England. It was a 12‑cylinder,

horizontally opposed, liquid cooled, valve-less,

2‑stroke cycle Diesel engine with a 3‑stage

turbine. It reached flight test but not

production.

The Allison engine

collected the exhaust gas from all 12 cylinders

and routed it to the turbine at the rear of the

engine through two exhaust tubes. The shaft from

the turbine ran through the centre of the first

stage supercharger impeller, back to the engine

and put its power directly into the crankshaft.

The turbine could not be connected to the

supercharger impeller because the supercharger was

driven by a variable speed transmission, which did

not run at a fixed speed ratio with respect to

either the crankshaft or the turbine. Since this

engine was to power a P‑63, it used an extension

shaft and a remote gearbox attached to the

crankshaft at the front of the engine at lower

left in the picture below. This engine represented

quite an advancement over the original 750 hp

engine.