gallstones

and gallbladder disease

Introduction

Gallstones (cholelithiasis) and inflammation of the gallbladder (cholecystitis)

affect over one million people in the US each year and 16-20 million

Americans have gallstones. 500,000 surgeries are performed every year to

remove gallbladders and stones. For the pilot and controller, this

condition presents minor medical certification issues. Reporting to the

FAA is usually rather straight forward.

Anatomy of the Gallbladder

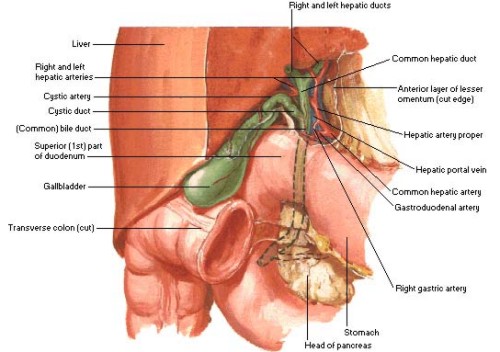

The

gallbladder is a large thumb sized sac that stores bile produced in the

liver. A system of connecting tubes known as ducts direct transfer of the

bile between the liver, the gall bladder and the small intestine, where

the bile aids in the digestion of fats and cholesterol. This system is

known as the bilary system. Think of the three ducts as forming a "Y".

Bile produced in the liver drains down one upper arm of the Y through the

hepatic duct. It moves up the upper arm of the Y, called the cystic duct,

to be stored in the gall bladder until it is needed for digestion. The

gallbladder then squeezes bile through the cystic duct into the common

bile duct which makes the lower leg of the Y. A muscle around the base of

the common bile duct relaxes to allow bile to flow into the intestine for

aid in digestion.

Stone Formation and Risk Factors

As long as there is unobstructed flow of bile through all three legs of

the Y, problems rarely occur. If one or more of the legs are blocked,

pressure can build as bile is continuously produced but not released. This

can cause pain and inflammation. Bile may sometimes form into stones from

the size of sand grains to nearly golf ball sized. The stones are composed

primarily of cholesterol and tend to occur when cholesterol concentrations

in the gall bladder increase compared to bile acid concentrations. These

stones may get stuck in the cystic duct and block the outflow. Less

commonly, they may get stuck in common bile duct and block flow of bile

from both the liver and the gallbladder. This is very serious and a person

quickly becomes ill and jaundiced. Ironically, the smaller granular stones

tend to clog the ducts more frequently. The larger stones tend to sit in

the gall bladder, rather than move down the ducts, because they are so

large. They may not cause any symptoms at all.

Risk factors for gall stone formation include obesity, rapid weight loss

by fasting, high fat diets, female hormones, increasing age, pregnancy,

sludging in the gall bladder and some medications.

Gallbladder Disease Symptoms

Gallstones frequently manifest themselves by a cramping pain below the

right rib cage after eating. Fatty meals may be particularly provocative.

In more serious cases, the pain can be incapacitating and confused with

ulcers, heart disease, kidney stones or pancreatitis. If associated with

fever, the condition requires immediate medical attention to treat the

cholecystitis. Sudden pain in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen that

may radiate to the right shoulder blade is termed "bilary colic." It may

persist for 1-4 hours and is followed by a dull upper abdominal pain for

about a day. The symptoms may be precipitated by a high fat meal (the FBO

"special") and relieved by limiting intake to non-fat liquids.

Initial treatment may include restricting oral intake to clear liquids or

nothing at all. Intravenous fluids, restricting oral intake, and

occasionally using a nasogastric tube to drain the stomach contents, will

allow the gallbladder to calm down. Fever and an elevated white blood cell

counts dictate the use of antibiotics. Surgeons are very reluctant to

operate while someone has a fever as the complication rate rises

dramatically. Many mild cases will not recur for extended periods,

particularly if one is cautious with their diet. Forgetting about the diet

may provide an uncomfortable reminder of the condition. Frequently, mild

symptoms may be treated with dietary restriction and watchful waiting.

This watchful waiting is an acceptable management technique. Many men will

have asymptomatic, or "silent" gallstones and up to 80% may never have any

symptoms nor require surgery.

Diagnosis of Gallstones

The definitive test to verify the presence of gallstones is the

gallbladder ultrasound, which gives a two dimensional picture using

Doppler imaging techniques to show the location and size of the stones.

Blood tests may lead to the suspicion of gall bladder disease with

elevated liver function tests and bilirubin. Occasionally, the diagnosis

is made by visualizing the stones during an x-ray or CT scan. Only 10-15%

of stones contain enough calcium to be visible by x-ray. To evaluate

inflammation and function of the gall bladder, scans using radioisotopes

injected in the blood and visualized with a nuclear imaging camera are

sometimes used. They are most useful in acute inflammation of the gall

bladder. Finally, an Oral Cholecystogram (OCG), which was the primary

diagnostic tool before ultrasound, is useful in assessing the function of

the gall bladder and ducts in those people who are not surgical

candidates.

Treatment

For people with recurrent gall bladder symptoms, both medical and surgical

techniques are available to treat the condition. Most commonly, surgery is

used to remove the gallbladder and its stones. The bile no longer is

stored in the gall bladder but is still produced in the liver and used for

digestion. Again, very few people with asymptomatic gall stones have any

need for treatment or surgery.

Surgical Treatment

Two main surgical techniques are used. One is the traditional

cholecystectomy where the abdomen is opened and the gall bladder and its

duct are tied off and removed. This requires general anesthesia and leaves

a significant scar under the right rib cage. President Lyndon Baines

Johnson demonstrates his gall bladder scar in a famous photograph of the

1960's. The recovery period for this is several weeks.

The alternative technique is much more popular today. It is called the

laparoscopic cholecystectomy. This technique uses three or four probes

inserted through tiny incisions in the abdominal wall to inflate the

abdomen with carbon dioxide, view the gallbladder lying behind and

underneath the liver, and remove the gallbladder and stones. The recovery

period is usually only a few days and scarring is nearly invisible.

Pilots/controllers undergoing these procedures may return to aviation

duties when cleared by their surgeon for full activity and they are

comfortable that they can perform all safety sensitive duties. Controllers

must also obtain clearance from the Regional Flight Surgeon before

returning to controlling. The operative report and discharge summary with

the surgeonís final note clearing the pilot/controller to return to

activity should be attached on the FAA Form 8500-8 at the next physical.

Follow up reporting is rarely required by the FAA.

Medical Treatment

Medical therapies to manage gallbladder disease are much less common than

surgical treatment. Only 10% of patients requiring treatment for

symptomatic gallbladder disease are candidates for medical treatment. One

technique uses medications alone to attempt to dissolve the stones. These

medications are called UDCA (ursodiol) and CDCA (chenodiol). They work

very slowly by decreasing cholesterol production in the liver. The

cholesterol in the stones is gradually diffused into the bile acid and

excreted in the intestine. About 50-60% of stones will dissolve over two

years. Use of these medications will require FAA review and approval

before flying or controlling. Remember, the underlying condition of

symptomatic gallstones may still be disqualifying, even if the medication

is tolerated well.

A newer medical therapy uses extracorporal shock waves, similar to the

technique used on kidney stones. The shock waves are focused on the stones

and attempt to blast them apart. Stones reform in about 20% of patients

and they generally are maintained on UDCA after treatment. Because of cost

and chances for recurrence, this treatment is not used often.

FAA Policy for Pilots & Controllers with Gallstones

The FAA will allow a pilot and controllers to perform duty with gallstones

that are not causing any symptoms. Frequently these stones are discovered

incidentally during another study such as an ultrasound or x-ray. If the

gallbladder is inflamed, a pilot or controller should not perform safety

sensitive duty during this period. In many cases, symptoms will resolve in

one to two weeks. They may then return to aviation duties and report the

episode at the next physical, if it resolves. Controllers should clear

through the Regional Flight Surgeons office before returning to work,

however. Those with chronic inflammation of the gallbladder are at risk

for recurrent attacks that may jeopardize flying safety. These individuals

should not fly or control until the problem is definitively corrected.

Pilots may return to flying after surgery for gallstones once the healing

is complete and their surgeon has released them to return to full

activity. Again, this surgery should be reported on FAA Form 8500-8 at the

time of the next physical examination. Reporting is not required for

pilots prior to the next examination if medications are not required. The

use of UDCA or CDCA for chronic treatment should be reported to the FAA

prior to returning to fly.

For controllers, reporting on the medical application is also required.

They must also clear through the Regional Flight Surgeon before retuning

to controlling duty. Remember, flying/controlling with active symptoms is

not appropriate.

|