spatial disorientation

Defines our natural ability to maintain our body orientation and/or

posture in relation to the surrounding environment (physical space) at

rest and during motion. Genetically speaking, humans are designed to

maintain spatial orientation on the ground. The three-dimensional

environment of flight is unfamiliar to the human body, creating sensory

conflicts and illusions that make spatial orientation difficult, and

sometimes impossible to achieve. Statistics show that between 5 to 10% of

all general aviation accidents can be attributed to spatial

disorientation, 90% of which are fatal.

Spatial Orientation in Flight

Spatial orientation in flight is difficult to achieve because numerous

sensory stimuli (visual, vestibular, and proprioceptive) vary in

magnitude, direction, and frequency. Any differences or discrepancies

between visual, vestibular, and proprioceptive sensory inputs result in a

sensory mismatch that can produce illusions and lead to spatial

disorientation. Good spatial orientation relies on the effective

perception, integration and interpretation of visual, vestibular (organs

of equilibrium located in the inner ear) and proprioceptive (receptors

located in the skin, muscles, tendons, and joints) sensory information.

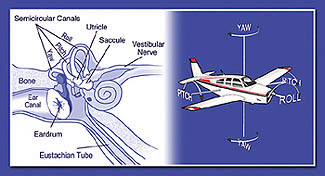

Vestibular Aspects

of Spatial Orientation

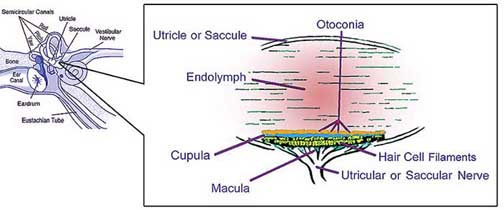

The inner ear contains the vestibular system, which is also known as the

organ of equilibrium. About the size of an pencil eraser, the vestibular

system contains two distinct structures: the semicircular canals, which

detect changes in angular acceleration, and the otolith organs (the

utricule and the saccule), which detect changes in linear acceleration and

gravity. Both the semicircular canals and the otolith organs provide

information to the brain regarding our body’s position and movement. A

connection between the vestibular system and the eyes helps to maintain

balance and keep the eyes focused on an object while the head is moving or

while the body is rotating.

The Semicircular Canals

The semicircular canals are three half-circular, interconnected tubes

located inside each ear that are the equivalent of three gyroscopes

located in three planes perpendicular (at right angles) to each other.

Each plane corresponds to the rolling, pitching, or yawing motions of an

aircraft.

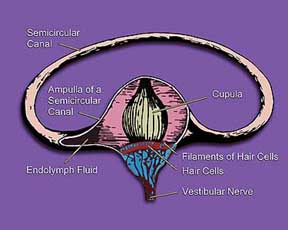

Each canal is filled with a fluid called endolymph and contains a motion

sensor with little hairs whose ends are embedded in a gelatinous structure

called the cupula. The cupula and the hairs move as the fluid moves inside

the canal in response to an angular acceleration.

The

movement of the hairs is similar to the movement of seaweed caused by

ocean currents or that of wheat fields moved by wind gusts. When the head

is still and the airplane is straight and level, the fluid in the canals

does not move and the hairs stand straight up, indicating to the brain

that there is no rotational acceleration (a turn).

If you turn either your aircraft or your head, the canal moves with your

head, but the fluid inside does not move because of its inertia. As the

canal moves, the hairs inside also move with it and are bent in the

opposite direction of the acceleration by the stationary fluid (A). This

hair movement sends a signal to the brain to indicate that the head has

turned. The problem starts when you continue turning your aircraft at a

constant rate (as in a coordinated turn) for more than 20 seconds. In this

kind of turn, the fluid inside the canal starts moving initially, then

friction causes it to catch up with the walls of the rotating canal (B).

When this happens, the hairs inside the canal will return to their

straight up position, sending an erroneous signal to the brain that the

turn has stopped–when, in fact, the turn continues. If you then start

rolling out of the turn to go back to level flight, the fluid inside the

canal will continue to move (because of its inertia), and the hairs will

now move in the opposite direction (C), sending an erroneous signal to the

brain indicating that you are turning in the opposite direction, when in

fact, you are actually slowing down from the original turn.

Vestibular Illusions

(Somatogyral - Semicircular Canals)

Illusions involving the semicircular canals of the vestibular system occur

primarily under conditions of unreliable or unavailable external visual

references and result in false sensations of rotation. These include the

Leans, the Graveyard Spin and Spiral, and the Coriolis Illusion.

The Leans.

This is the most common illusion during flight and is caused by a sudden

return to level flight following a gradual and prolonged turn that went

unnoticed by the pilot. The reason a pilot can be unaware of such a

gradual turn is that human exposure to a rotational acceleration of 2

degrees per second or lower is below the detection threshold of the

semicircular canals. Levelling the wings after such a turn may cause an

illusion that the aircraft is banking in the opposite direction. In

response to such an illusion, a pilot may lean in the direction of the

original turn in a corrective attempt to regain the perception of a

correct vertical posture.

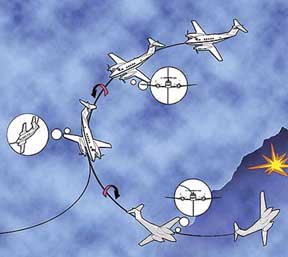

The Graveyard

Spin is an illusion that can occur to a pilot who intentionally

or unintentionally enters a spin. For example, a pilot who enters a spin

to the left will initially have a sensation of spinning in the same

direction. However, if the left spin continues the pilot will have the

sensation that the spin is progressively decreasing. At this point, if the

pilot applies right rudder to stop the left spin, the pilot will suddenly

sense a spin in the opposite direction (to the right). If the pilot

believes that the airplane is spinning to the right, the response will be

to apply left rudder to counteract the sensation of a right spin. However,

by applying left rudder the pilot will unknowingly re-enter the original

left spin. If the pilot cross checks the turn indicator, he/she would see

the turn needle indicating a left turn while he/she senses a right turn.

This creates a sensory conflict between what the pilot sees on the

instruments and what the pilot feels. If the pilot believes the body

sensations instead of trusting the instruments, the left spin will

continue. If enough altitude is lost before this illusion is recognized

and corrective action is taken, impact with terrain is inevitable.

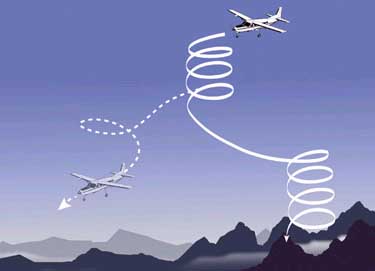

The Graveyard

Spiral is more common than the Graveyard Spin, and it is

associated with a return to level flight following an intentional or

unintentional prolonged bank turn. For example, a pilot who enters a

banking turn to the left will initially have a sensation of a turn in the

same direction. If the left turn continues (~20 seconds or more), the

pilot will experience the sensation that the airplane is no longer turning

to the left. At this point, if the pilot attempts to level the wings this

action will produce a sensation that the airplane is turning and banking

in the opposite direction (to the right). If the pilot believes the

illusion of a right turn (which can be very compelling), he/she will

re-enter the original left turn in an attempt to counteract the sensation

of a right turn. Unfortunately, while this is happening, the airplane is

still turning to the left and losing altitude. Pulling the control

yoke/stick and applying power while turning would not be a good

idea–because it would only make the left turn tighter. If the pilot fails

to recognize the illusion and does not level the wings, the airplane will

continue turning left and losing altitude until it impacts the ground.

The Coriolis

Illusion involves the simultaneous stimulation of two

semicircular canals and is associated with a sudden tilting (forward or

backwards) of the pilot’s head while the aircraft is turning. This can

occur when you tilt you head down (to look at an approach chart or to

write a note on your knee pad), or tilt it up (to look at an overhead

instrument or switch) or tilt it sideways. This produces an almost

unbearable sensation that the aircraft is rolling, pitching, and yawing

all at the same time, which can be compared with the sensation of rolling

down on a hillside. This illusion can make the pilot quickly become

disoriented and lose control of the aircraft.

Two otolith organs, the

saccule and utricle, are located in each ear and are set at right angles

to each other. The utricle detects changes in linear acceleration in the

horizontal plane, while the saccule detects gravity changes in the

vertical plane. However, the inertial forces resulting from linear

accelerations cannot be distinguished from the force of gravity;

therefore, gravity can also produce stimulation of the utricle and saccule.

These organs are located at the base (vestibule) of the semicircular

canals, and their structure consists of small sacs (maculas) covered by

hair cell filaments that project into an overlying gelatinous membrane (cupula)

tipped by tiny, chalk-like calcium stones called otoconia.

Change in Gravity

When the head is tilted, the weight of the otoconia of the saccule pulls

the cupula, which in turn bends the hairs that send a signal to the brain

indicating that the head has changed position. A similar response will

occur during a vertical take-off in a helicopter or following the sudden

opening of a parachute after a free fall.

Change in Linear Acceleration

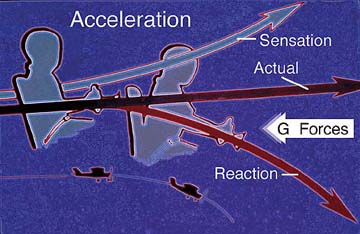

The inertial forces resulting from a forward linear acceleration

(take-off, increased acceleration during level flight, vertical climb)

produce a backward displacement of the otoconia of the utricle that pulls

the cupula, which in turn bends the hair cell filaments that send a signal

to the brain, indicating that the head and body have suddenly been moved

forward. Exposure to a backward linear acceleration, or to a forward

linear deceleration has the opposite effect.

Vestibular

Illusions

(Somatogravic - Utricle and Saccule)

Illusions involving the utricle and the saccule of the vestibular system

are most likely under conditions with unreliable or unavailable external

visual references. These illusions include: the Inversion Illusion,

Head-Up Illusion, and Head-Down Illusion.

The Inversion

Illusion involves a steep ascent (forward linear acceleration) in

a high-performance aircraft, followed by a sudden return to level flight.

When the pilot levels off, the aircraft’ speed is relatively higher. This

combination of accelerations produces an illusion that the aircraft is in

inverted flight. The pilot’s response to this illusion is to lower the

nose of the aircraft.

The Head-Up

Illusion involves a sudden forward linear acceleration during

level flight where the pilot perceives the illusion that the nose of the

aircraft is pitching up. The pilot’s response to this illusion would be to

push the yolk or the stick forward to pitch the nose of the aircraft down.

A night take-off from a well-lit airport into a totally dark sky (black

hole) or a catapult take-off from an aircraft carrier can also lead to

this illusion, and could result in a crash.

The Head-Down

Illusion involves a sudden linear deceleration (air braking,

lowering flaps, decreasing engine power) during level flight where the

pilot perceives the illusion that the nose of the aircraft is pitching

down. The pilot’s response to this illusion would be to pitch the nose of

the aircraft up. If this illusion occurs during a low-speed final

approach, the pilot could stall the aircraft.

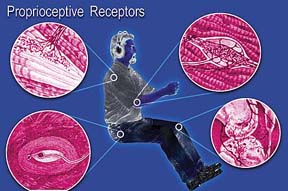

The

Proprioceptive Receptors

The proprioceptive receptors (proprioceptors) are special sensors located

in the skin, muscles, tendons, and joints that play a very small role in

maintaining spatial orientation in normal individuals. Proprioceptors do

give some indication of posture by sensing the relative position of our

body parts in relation to each other, and by sensing points of physical

contact between body parts and the surrounding environment (floor, wall,

seat, arm rest, etc.). For example, proprioceptors make it possible for

you to know that you are seated while flying; however, they alone will not

let you differentiate between flying straight and level and performing a

coordinated turn.

How to Prevent Spatial Disorientation

The following are basic steps that should help prevent spatial

disorientation:

Take the opportunity to

experience spatial disorientation illusions in a Barany chair, a Vertigon,

a GYRO, or a Virtual Reality Spatial Disorientation Demonstrator.

-

Before flying with less than 3 miles visibility, obtain training and

maintain proficiency in airplane control by reference to instruments

-

When

flying at night or in reduced visibility, use the flight instruments.

-

If

intending to fly at night, maintain night-flight currency. Include

cross-country and local operations at different airports.

-

If

only Visual Flight Rules-qualified, do not attempt visual flight when

there is a possibility of getting trapped in deteriorating weather.

-

If

you experience a vestibular illusion during flight, trust your

instruments and disregard your sensory perceptions.

Spatial Disorientation and Airsickness

It is important to know the difference between spatial disorientation and

airsickness. Airsickness is a normal response of healthy individuals when

exposed to a flight environment characterized by unfamiliar motion and

orientation clues. Common signs and symptoms of airsickness include:

vertigo, loss of appetite, increased salivation and swallowing, burping,

stomach awareness, nausea, retching, vomiting, increased need for bowel

movements, cold sweating, skin pallor, sensation of fullness of the head,

difficulty concentrating, mental confusion, apathy, drowsiness, difficulty

focusing, visual flashbacks, eye strain, blurred vision, increased

yawning, headache, dizziness, postural instability, and increased fatigue.

The symptoms are usually progressive. First, the desire for food is lost.

Then, as saliva collects in the mouth, the person begins to perspire

freely, the head aches, and the airsick person may eventually become

nauseated and vomit. Severe airsickness may cause a pilot to become

completely incapacitated.

Although airsickness is uncommon among experienced pilots, it does occur

occasionally (especially among student pilots). Some people are more

susceptible to airsickness than others. Fatigue, alcohol, drugs,

medications, stress, illnesses, anxiety, fear, and insecurity are some

factors that can increase individual susceptibility to motion sickness of

any type. Women have been shown to be more susceptible to motion sickness

than men of any age. In addition, reduced mental activity (low mental

workload) during exposure to an unfamiliar motion has been implicated as a

predisposing factor for airsickness. A pilot who concentrates on the

mental tasks required to fly an aircraft will be less likely to become

airsick because his/her attention is occupied. This explains why sometimes

a student pilot who is at the controls of an aircraft does not get

airsick, but the experienced instructor who is only monitoring the student

unexpectedly becomes airsick.

A pilot who has been the victim of airsickness knows how uncomfortable and

impairing it can be. Most importantly, it jeopardizes the pilot’s flying

proficiency and safety, particularly under conditions that require peak

piloting skills and performance (equipment malfunctions, instrument flight

conditions, bad weather, final approach, and landing).

Pilots who are susceptible to airsickness should not take anti-motion

sickness medications (prescription or over-the-counter). These medications

can make one drowsy or affect brain functions in other ways. Research has

shown that most anti-motion sickness medications cause a temporary

deterioration of navigational skills or other tasks demanding keen

judgment.

An effective method to increase pilot resistance to airsickness consists

of repetitive exposure to the flying conditions that initially resulted in

airsickness. In other words, repeated exposure to the flight environment

decreases an individual’s susceptibility to subsequent airsickness.

If you become airsick while piloting an aircraft, open the air vents,

loosen your clothing, use supplemental oxygen, keep your eyes on a point

outside the aircraft, place your head against the seat’s headrest, and

avoid unnecessary head movements. Then, cancel the flight, and land as

soon as possible.

|