|

pilot report Bellanca 14-13 Cruisair

by

Budd Davisson

We fly the

Cardboard Constellation

What is it

about wood that scares the living hell out

of a large part of the US pilot population?

Whatever gives those pilots the termite

heebie geebies, it is also responsible for

most of the controversy surrounding

wooden-winged airplanes and especially the

fabled line of Bellanca low-wingers.

Bellanca low-wing flying

machines cleave a very defined line between

pilots that clearly puts the aircraft into

either a "love it" or "leave it" category.

Most would just as soon forget Bellancas

because they've heard all the tales about

wood wings failing - spars made into

sponge-like masses by alien organisms - and

plywood punched into screen wire consistency

by little boring things with green eyes and

pointy teeth.

Let's set the record

straight right up front: The most accurate

information available indicates only four

known in- flight failures of Bellanca wings.

At least one of those had to do with

aerobatics in extreme turbulence. All

failures were in the later Viking series

which were heavier and much faster than the

early airplanes. Despite these statistics,

pilots still are much more willing to climb

into a V-tailed doctor/lawyer killer than a

Bellanca. This makes little sense since the

Bonanza has staggering wing failure

statistics. The real shame is that by

avoiding Bellanca low-wingers, a pilot is

depriving himself of one of aeronautica's

greatest pleasures.

To put it simply:

Regardless of the age, model or lineage,

Bellanca airplanes are among the best

flying, best feeling cross- country

airplanes ever built. That's only one man's

opinion so I don't want a deluge of mail

from Navion/Mooney/Bonanza/Comanche/Wilga/Storch

owners. I also prefer redheads over blondes

and Brownings over Berettas.

While we're at it, let's

get another fact out of the way: Yes, wood

deteriorates and that bit of space-age

wisdom is about two notches below common

sense. A lot of Bellanca wood has

deteriorated because common sense in storing

aircraft is not always exercised during that

middle part of an airplane's life span when

the craft is so obsolete it doesn't qualify

for "used" category and hasn't yet made

"classic" status. Put wood out in the

elements and it will, eventually, be much

the worse for the wear. Is aluminium that

much different?

Bellanca, as a name, is nearly as old as

aviation. Guiseppe was building some of the

most useable airplanes in the world long

before North American was born, before Bill

Piper decided to get into the airplane

business and before Clyde Cessna, Lloyd

Stearman and Walter Beech were anything

other than Travel Air employees, Bellanca's

Pacemaker and Skyrocket designs were working

machines that may not have been as famous as

many, but they were respected by those who

used and flew them. We were well into the

1980s before the last Bellanca was retired

in the Canadian/Alaskan bush. And none of

them were much less than 60 years old!

Bellanca aircraft were

always remarkably efficient when measured

against the mission for which they were

designed. The Pacemaker and Skyrocket could

carry huge loads and were fairly fast for

their size. So, it was only natural that

when Guiseppe decided to get into the small,

personal airplane market, his designs should

be just as efficient. In 1937 he introduced

models 14-07 and 14-09, referred to as the

"Junior:' These were lithe little

three-place low-wing machines that used a

variety of engines, including the tiny

LeBlond radial. With only 100-125 hp on tap

the design was incredibly fast, giving over

1 mph per horsepower. The mile/per

horsepower became a Bellanca trademark. Only

approximately 50 Juniors were built before

the war diverted Bellanca's attention to

more pressing matters.

After the war a new

design, the 14-13, was introduced and used

either 150 or 165 hp Franklin six cylinder

engines and was named the "Cruisair".

Structurally, the plane was essentially the

older Junior with numerous modifications,

but the concept remained the same. The wing

was a relatively high-aspect ratio, all-wood

unit that utilized a special Bellanca

airfoil. The landing gear retracted Seversky-style,

meaning the gear folded straight back -

leaving about half of the wheel exposed. The

fuselage was traditional rag and tube which

enveloped the passengers in a crash cage

that looks as if it was designed

specifically for running through trees. The

foregoing is an accurate description of any

and all Bellanca low-wing 14 series designs.

The concept hasn't changed from the Junior

to the 1988 Viking (yes, there are 1988

Vikings). It worked then and it works now.

With over 50 years of

Bellancas to choose from, the choice was

difficult but we decided to concentrate on

the early - and still plentiful - 14-13

series. In researching this series, we

learned lots about Bellancas in general and

the accompanying sidebar is an attempt to

furnish some chronological information about

the development of the descendants of the

14-13.

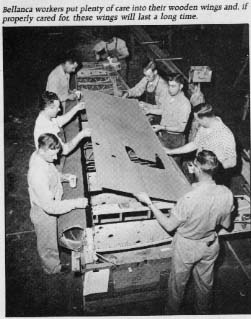

The 14-13 Cruisair was Bellanca's big hammer

for the aviation boom that was supposed to

follow the war. The boom never happened but

Bellanca (along with everybody else in

aviation) didn't know that until they had

run a bunch of airplanes out the door. In

total something over 580 Cruisairs were

built 1946-1949, Like today's Viking. they

were essentially hand-crafted airplanes,

Unlike the Cessnas and Beeches of the era

(G17S not withstanding), the structure of

the Cruisair didn't lend to mass production

since tubing goes together with a pair of

hands and a welding torch. The wings require

hand fitting thousands of small parts.

Fabric covering, of course, demands an

enormous amount of elbow grease. These

factors are the primary reason Cruisairs

didn't totally flood the market. as did

Cessnas and other airplanes that demanded

less man-hours to build. In 1946 an amazing

35.000 plus airplanes were produced (compare

that to 1987's 1000 odd machines) and only a

small number were Bellancas.

With a 150 or 165 hp six

cylinder Franklin, the Bellanca's were fast.

The book cruise figures were 150 mph plus

which was comparable to the higher-powered

Cessna 195 or Beech Bonanza. Even more

amazing was the airplane's maximum dive

speed (they didn't call it Vne in those

days) of 216 mph. That figure bespoke of

strength far in excess of that required.

At 2150 pounds (an early

Viking is 500-600 pounds heavier) the

airplane had approximately 950 pounds useful

load with two 20 gallon wing tanks. An

optional 12 gallon aux tank could be fitted

under the rear seat. but very few were so

outfitted. Propeller options included the

Sensenich fixed club or a controllable

Sensenich that reportedly had such a bad

reputation even the factory has tried to

disown the design. The propeller of choice

was usually the well-known Aeromatic

automatic adjustable or, occasionally. a

two-position variation of the Aeromatic.

The old Cruisair is one

of those airplanes that has al-ways been

there." There is something about its lines

that don't really fit any era. Even when

new, the Cruisair was " different" for lack

of a better term. Today, the design

obviously harkens back to an older era but

it's hard to decide which era. The Bellanca

is sleek, but the rectangular fuselage cross

section gives corners that modern eyes don't

normally associate with streamlining. But to

those with a certain kind of eye. the

Bellanca has always appeared just right.

I have one of those eyes.

Probably the only reason I have never owned

a triple-tail Bellanca (we used to call them

"Cardboard Constellations," but now we have

to explain the Constellation part to the

younger generation), is I seldom use

airplanes to go anywhere and I'm the only

one in my family who flies. If I had any

need at all for a cross-country airplane,

the triple-tailed Bellanca would be on the

top of the list.

Finding 14-13's

isn't as easy as it used to be because they

currently change hands much less frequently

and owners have wised up to the secret of

Bellanca longevity which is good hangar

space. We no longer see Bellancas

languishing around on back tie-down lines.

Fortunately. there are two Bellancas

hangared with Aero Sport in St. Augustine.

Florida, and one of the owners, Bob Meadows,

was more than accommodating. It seems

Bellanca owners like nothing better than to

show other pilots what they are missing! The

Meadows Bellanca is essentially a dead-stock

Cruisair. It hasn't received one of the many

engine transplants so common (bigger

Franklins with constant speeds. Lycomings.

etc.) and, with the exception of what appear

to be later fiberglass wing fairings. it has

none of the many speed kits available.

In walking around a

taildragger Bellanca, the first thing that

pilots say is "The gear looks bent" The

axles are mount-ed on the gear legs in such

a way that the tires tilt outward and look

really awkward. The official explanation is

the prototype had much less dihedral and

proved too unstable so Bellanca increased

the dihedral. This change put the tires at

an angle to the ground but to have changed

that angle would have required entirely new

retracting geometry for the gear legs and

the factory decided it wasn't worth the

effort and/or money. Forty years later, they

still look bent.

The gear is a welded up

affair that uses a really ingenious

retraction and lock down system. A hand

operated (an electric conversion is often

done) screw jack pulls back on the top of a

long over-centre strut which pulls the gear

back and up. The system is simplicity

personified and easy to rig and inspect.

Another item often

mentioned are the eyebrow cuffs on the

cowling air inlets. They look like

afterthoughts. which they were. While

climbing, the Franklin apparently doesn't

get enough cooling air with the stock

cowling, so a set of air-catchers was

designed and approved. They work, but they

sure do look like somebody goofed somewhere

along the line.

Boarding the airplane

requires stepping over the spring loaded

flap and leaning well forward to grab the

edge of the door to stabilize yourself,

since there is no hand hold. Many Bellancas

have a small handhold cut-out in the top

edge of the fuselage to help folks get in

but Meadow's airplane didn't have this

feature.

The door opening extends toward the middle

of the fuselage. so contorting is cut to a

minimum when stepping into the cabin. This

is when folks generally make their second

comment about Cruisairs. "Boy. it sure is

cozy!" or some-thing like that is uttered

and they are right. Speed on low horsepower

means minimum drag and that means minimum

frontal area and that's what the Cruisair

has, at the expense of the front seat

passengers. After you've been in the

airplane a bit, you learn what to do with

the arm that always seems to be entangled

with the body in the other seat so the

situation doesn't seem nearly so tight.

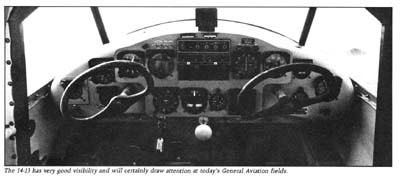

A common complaint about

Cruisairs was there wasn't room in the

instrument panel for radios. The panel

really is narrow, but modern electronics

have come to the rescue, replacing the old

Narco Superhomers and later KX-150s with

boxes that take up half the space. Outfitted

with modern slim line radios and LORAN,

about all that can be said about the panel

is it looks "tidy:' The top of the original

panel is quite low and gives excellent

visibility and the new radios eliminate the

need to build the often-seen "hump" that

sticks up into the field of vision.

Meadows literally turned

his airplane over to Carl Pascarell and

myself to go see what the airplane does and

doesn't do and Carl and I went out to see

what we could see.

The first thing I found

on taxiing was the tailwheel would

eventually point the airplane where it was

supposed to be pointed, but on the ramp a

touch of brake now and then was needed.

Fortunately. visibility over the nose is 7

on a 1 to 10 scale. By stretching hard, it's

even possible to see completely over the

nose.

The seat is definitely

not of the adjustable variety, the bottom

frame being part of the fuselage tubing

structure. It was, however situated just

right for my very average five-ten frame.

The brake pedal adjustment was a little out

of whack, since it was hard to get full

rudder without getting a little of the

expander tube brakes into the act. This

information was forwarded from Carl who was

sitting in the left, so I could fly with my

right hand. I had no brakes on my side,

which meant requests for".. . give me a

touch of right.' At the end of the runway a

quick run-up indicated several things. The

most important was that the 150 Franklin was

running fine and carb heat was good for a

nearly 200 rpm drop.. The mag check also

showed the smoothness of a 6 cylinder and

how little sound deadening there was in the

cabin structure.

Having flown the airplane

previously. Carl was rather insistent on two

points prior to takeoff: The airplane would

pull fairly hard to the left because of a

gear geometry problem and most of the

steering was going to come from the

tail-wheel. That was another way of saying,

as soon as the tail was up, expect the plane

to turn left.

Pushing the throttle knob to the panel, the

Franklin began dragging us down the concrete

while I concentrated on the edge of the

runway. St. Augustine has these enormous

wide, runways. I elected to use the right

half only to have better visual references.

As we leisurely accelerated, I purposely

kept the tail nailed down until the

slightest hint the airplane was getting

light. Visibility to that point had been

just fine and got positively wonderful when

I gently hoisted the tail. A right crosswind

was working to keep the airplane headed dead

straight and I made no effort to lift off.

The Bellanca trundled ahead while I tried to

keep the tail just a little low and it flew

off somewhere around 60 mph.

Keeping the nose down

until we had 85 mph on the clock, I waited

until we had 300 feet before cranking the

landing gear up. The handle is mounted on a

covered bracket between the two pilots at

the front edge of the seat. The polished

wooden grip showed it had been used plenty

and, as I grabbed it, I was mindful of

holding the landing gear handle with one

hand and the yoke with the other and I

imagined doing a push-me pull-you routine

that would result in a sawtoothed climb

profile. I was counting as I cranked but

there was no tendency to porpoise the nose.

As I counted into the

teens, my shoulder reminded me how torn-up

cartilage hated this kind of activity. By

the twenties I told Carl I was going to name

the article "Fly a Cruisair... if You're Man

Enough!" By that time the gear was going

over centre and moving easier. It wasn't

until the late thirties that the handle

stopped moving. Finally! It took 37 turns to

get the gear retracted. The screw jack

mechanism is its own up-lock and the

over-centre arm locks it down. There is no

internal gear position indicator. The pilot

knows if the gear is up or down by looking

at a half inch piece of painted metal

sticking through the surface of the left

wing root. The top is painted white, and

that's all that's supposed to be showing if

the gear is down and locked.

By this time, the

airplane was moving away from the ground at

about 700 fpm and not straining a bit. With

some airplanes, it feels as if climbing is

work but with that long wing, the Cruisair

didn't even break a sweat.

Carl and I talked about

this and we agreed that with some flying

machines, it takes a long time in them to

feel comfortable while others seem to fit

together immediately. The Cruisair fit

before it was even off the ground! For one

thing, the smallish cockpit seemed to get

larger as soon as we left the ground. More

importantly, the input of the controls and

the response of the airplane was perfectly

matched. The Bellanca seemed to know how I

wanted an airplane to feel. In a Cessna or a

Piper there is no doubt you are manipulating

a machine that flies. The mechanics of the

machine are always there to remind the pilot

that his thoughts and actions are translated

by a bunch of levers and gears that

eventually becomes flight. Not so the

Bellanca.

We're talking real

intangibles and possibly more than just a

little personal taste.

Whatever it is, the Bellanca has something

found in relatively few light airplanes.

That "just right" feeling doesn't happen

often - and almost never in four-place

transportation machines. The ailerons are

not only light, but response is immediate

without being twitchy. The breakout forces

exactly match the control forces so the

lateral control is a syrupy continuum, that

is the trademark of all Bellancas. When no

rudder is used, there is an amazing lack of

adverse yaw which would be expected with

wings that long. And the rudder and

elevator? They mix in so naturally with the

ailerons that little thought is given to how

they actually feel.

The Cruisair is a

40-year-old airplane and things like the

gear retraction system and elevator trim

reconfirm that age. The trim is mounted in

the middle of the top of the wind-shield and

faces the wrong way. . . the crank is

pointed forward. This is even worse than the

old Piper system. Fortunately the trim is

reasonably powerful, so the second it is

moved there is no doubt whether it is being

moved correctly. Exactly 50 percent of the

time I was wrong.

At altitude, I pulled the

carb heat and then the power, holding the

nose just above the horizon. Slowly the

speed bled off until I was sitting there

with the yoke against my chest, the airspeed

at 50-52 mph and the nose barely bobbing up

and down. The VSI read 700 fpm down. With

flaps the speed was well under 50 mph. We

didn't try stalls with the gear down because

I didn't know how much shoulder was left.

Most of the time we were

cruising around at 2400 rpm which gave an

indicated of about 132 mph. We wanted to do

some speed runs, but the St. Augustine area

isn't exactly flush with cornfields and

section lines so we had to content ourselves

with some two-way runs down St. Augustine's

8000 ft runway The results were a little

disappointing... 125 mph. In such a short

distance, any changes in altitude or heading

really affect the outcome.

At this point, a

discussion of speed is important. The

Bellanca Cruisair is an example of an

airplane that gets most of its speed out of

aerodynamics, not horsepower. The fuselage

is carefully designed to be an airfoil that

carries its own weight. The wings are long

and made to be slippery.

In fact, the entire

airframe is made to be slippery. Now, show

me one 42-year-old beauty that doesn't have

to work just a little to be slippery. Years

take their toll. Wing skins are wavy.

Fairings not tight. Maybe the wings aren't

rigged just right. In this particular

Cruisair, a little right aileron was needed

to keep it headed straight. On most

airplanes that would be no big deal, but on

a low powered. made-to-be-clean air-frame

like a Bellanca. the results are disastrous.

The boys who spend all

their time tinkering with Bellancas say it

takes only attention to detail and rigging

to get book speed numbers. And then, there

are a number of mods available that take

even more advantage of the airframe design.

Done with our speed runs.

I steeled myself for lowering the landing

gear. Bringing the speed down to 100 mph, I

started cranking and found putting the gear

down was much, much easier than bringing it

up. Something having to do with gravity, I

suspect.

On a tight downwind, I

reached way forward under the instrument

panel and found the flap handle, pulling it

back one notch for half flaps. The speed

stabilized at 85 mph with practically no

trim change. The same was true when full

flaps was selected on final and the speed

allowed to settle on 80 mph.

Approach was a simple

matter of pointing the nose at the numbers

and watching as the ground came up. Power

off, we settled into a groove that shallowed

out as I broke the glide and started feeling

for the ground. In earlier landings Carl had

found that with only two people on board the

airplane ran out of elevator in a three

point which put the Cruisair on the mains

with the tail several inches up. I knew no

way to prevent that, so I just concentrated

on the edge of the runway. keeping the

airplane straight and toying with the yoke

to keep just dear of the runway. By this

time the speed must have been (I was too

busy to look) in the low 50s and everything

was happening in slow motion. Then, I felt

the yoke hit the stop and at the same time

the gear squished on to the pavement. If the

tailwheel wasn't touching, I couldn't tell

because the touchdown was so slow and soft,

the plane just melted onto the runway.

We had reversed direction

on the runway and were landing opposite to

the direction we had taken off, so the wind

was from the left. And I knew it was there.

The wind and gear geometry called for

nailing the right rudder against the floor,

while the airplane ever so gently and slowly

moved to the left. This was happening in

slow, slow motion and I kept pleading for a

little right brake from Carl, but he sat

there heckling me for not being able to keep

it straight. Eventually, we coasted to a

stop and that was that. The airplane is very

low demand, as taildraggers go. Sort of like

a fat Citabria, only easier.

Normally, I would have

wanted to make a bunch more landings to get

comfortable in the airplane, but something

told me this wasn't necessary. Every single

part of the flight had been under total

control because the airplane had done

everything I asked. If the pilot asks the

Cruisair to do the right things, the flight

will always be a good one. And the critical

areas - such as takeoff and landing - happen

at such slow speeds. the pilot doesn't need

to be a Pitts type tail-dragger driver to

stay ahead of the Cruisair.

When we were sitting

around on Aero Sports' famed front porch (it

might as well have score cards to hold up

since everyone grades the landings so

vehemently) Carl and I both had the same

thoughts: The Cruisair airframe is a hell of

a good place to begin building a totally

useful. classic cross-country airplane. If

completely restored, the Cruisair would give

the pilot a classic machine that is every

bit as useful as anything available. And

with subtle, mostly invisible modifications,

the Bellanca could be a real hummer. It does

have some drawbacks, the condition of the

wood wings be-ing one and the smallish cabin

another. But those things are all livable.

Sitting in the back seat. I found my head

brushing the headliner but the unusual

windows gave the best view I've ever seen in

the back seat of an airplane.

This is not an every

person's airplane. To a lot of pilots, it

would be too classic and they wouldn't want

to worry about the fabric and the wood. They

might not like the tight cabin or the skill

requirement - small though it may be -the

tailwheel demands. These might overshadow

the air-plane's delightful handling and its

vintage charisma. For those pilots, there

are plenty of the more traditional choices

and that's understandable. Every pilot

should fly a Bellanca, any Bellanca. at

least once so they know what kind of choice

they are making. They should know what they

are missing. If they don't buy a Bellanca,

however, that's okay because it leaves that

many more of them for the rest of us! BD.

|