|

Group Ownership

GROUP OWNERSHIP OF an aircraft can mean lower costs, better availability and provide the real satisfaction of aircraft ownership. Many such groups operate very successfully on an informal basis, particularly when an aircraft is bought by a couple of like-minded friends. But experience has shown that, as the size of a group increases or membership changes, problems and disputes can arise--and the resolution of these can often cost more than the original savings, and certainly raise anxiety levels. One method of guarding against difficulties is the adoption of a formal agreement between group members. There are plenty of excellent lawyers who can advise a group and draw up a written agreement, but for many pilots this might go against the ethos of informality and cost saving and, let's face it, if you paid me for the service, I'm only going to fritter your money away on avgas. So the purpose of this article is to consider some of the points you might want to cover if you are writing the agreement for yourself.

It would be as well to start by giving the group a name, stating that the objective of the group is to operate aircraft X, and then to define and limit the number of equal shares in the group. This might sound pretty obvious, but I once came across a case where a group member explained that a friend of his (assumed to be a former member of the group) had still been flying the aircraft, without the agreement or knowledge of the rest of the group--he claimed he had sold the friend only part of his share. He could see nothing unreasonable about this and after many months of arguing, the group ended up disbanding. The group member had allowed a person who had never had any connection with the group to fly the aircraft. His claim of having sold part of his share to the 'new member' increased the numbers of members and created unequal share holdings.

What happens when a member wants to leave the group? Does the group disband, could or should the share be bought in by the rest of the group or can it be sold to an outsider? In law, a departing member can force the sale of the whole aircraft and claim an appropriate share of the proceeds. However, the remaining members may not want to lose the aircraft and at the same time they may want some control over any new member. Matters to be considered are:

The final item may become relevant if the share is to be bought in by the group. I'll now explain the first two points.

As far as the law is concerned, an interest in jointly owned property is an interest in the proceeds of sale or in any income derived from the property. There is no automatic right of possession or use of the property or chattel. It follows that in law a joint owner of an aircraft does not have an automatic right to fly it or even fly in it, they merely have an interest in its sale or in any profit derived from operating it. This does have the advantage that a group can stipulate minimum qualifications or criteria in order for a member to have the right to use the aircraft. This is an important consideration because under the Civil Aviation Act there is liability against aircraft owners for any loss or damage occasioned by an aircraft in flight without need for proof of negligence. Further, there have been instances of insurers repudiating claims where an aircraft is flown in breach of the Air Navigation Order and that covers a very wide field including negligence. This is why it is important not only to have good insurance cover but also important to regulate the use of the aircraft and the standards of those who may fly it. You will probably want to stipulate minimum qualifications and/or the completion of a satisfactory check flight or training before a member may fly the aircraft. You will want to specify what the training is and who is to carry out the check flight and, for the sake of completeness, state that members will only operate the aircraft with a current medical certificate and rating(s) and at all times in accordance with the provisions of the Air Navigation Order.

It is probably as well to set out a member's liabilities for costs and the payment of bills. Clearly in most groups there will be a treasurer but it might make his or her job easier if everybody knows their obligations. Which costs are to be fixed i.e. hangarage, insurance and so forth, and which should be based on the hourly rate? As an example, should there be a reserve fund for maintenance built into the hourly cost or does everybody pay an equal share? Resentment can very quickly arise when an unexpected (or even expected) bill comes in if some members use the aircraft significantly more than others. After all, the more hours flown, the sooner the maintenance bills come round.

There should be an agreed mechanism for booking the aircraft and possibly a limitation on the bookings that can be made. There is nothing more frustrating than having paid for the greater availability of having your own aircraft and then finding that another group member has booked every weekend for the whole of the summer. On the other hand, members might want the ability to go on a long trip and so you may wish to allocate each member a certain number of days each year in respect of which, with suitable notice, they can exercise a priority over booking.

What happens if something goes wrong and members fall out? Obviously, members ultimately have recourse to the courts to settle any dispute but the costs of litigation are such that in many cases you might just as well give the aircraft away--doing this at an early stage will at least save an awful lot of anxiety. In my view, the most important part of any agreement is an arbitration clause. That is to say that in the event of a dispute the members agree to be bound by an arbitrator's decision. Arbitration is a relatively informal method of dispute resolution and involves the appointment of an independent party who can receive representations from both sides to a dispute and either seek to resolve the problem or give a binding judgement in respect of the matter in contention. While an arbitrator is entitled to some recompense for their time and trouble, it is a significantly less expensive procedure than litigation through the courts and may avoid the involvement of lawyers. Further, it is possible to appoint an arbitrator who has some expertise in the matter in contention. For example, if the dispute is over the flying ability of a particular member or the manner in which they are using the aircraft, the CFI of a local flying club could be appointed as arbitrator. If the aircraft is operated under a Permit to Fly then the PFA could be asked to appoint a suitable arbitrator. It is as well to define the method of appointment e.g. 'In the event of any dispute arising out of this agreement the parties agree that the matter shall be determined by an independent arbitrator to be appointed by the Chairman of the X Strut of the Popular Flying Association and further agree to be bound by such determination or decision' (or '...appointed by the parties...' or '...appointed by the CFI of the X flying club...').

Flexibility is important and there will be individual requirements that a group will want to add to any agreement to cover the operation of their own particular pride and joy. All these points, covering both obvious and far-fetched circumstances, are relevant to actual disputes that I have encountered or have heard of over the years. These have ranged from the mildly irritating to the bizarre. In one case a group owner, having booked the aircraft, arrived at the airfield with his friends for a trip to France to discover that the aircraft departed in the opposite direction half an hour earlier with another group member at the controls. In another case a co-owner 'kidnapped' the aircraft and hid it from the rest of the group during the course of a dispute between two other group members as to the ownership of a share. We plan for the unexpected and the unlikely when airborne; it can be as well to do the same on the ground.

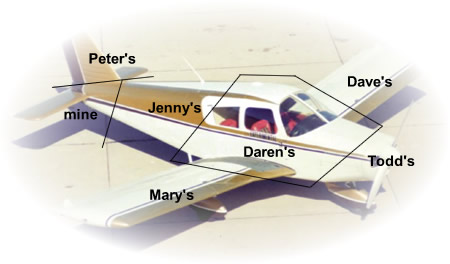

Shared ownership The

first thing to say, (and I know that this is probably blindingly obvious),

is that any shared bill, whatever the bill is for, is better by a factor

of the number of sharers, than one which you have to settle by yourself.

By now anyone reading this will have been involved with aircraft long

enough to know that whatever it is you need for your particular machine is

just bloody expensive, so don't take the preceding lightly. (My group

recently had a good autopilot system fitted to our aircraft and we were

able to budget for about the best there is, without breaking the bank, as

opposed to compromising or not even considering the project at all).

Clearly, the other major costs like insurance (currently about £2800 per

annum for our Rockwell), hangarage (another £2500) and scheduled

maintenance, (budgeted for £6500 per annum), are prohibitive for anyone

who doesn't have the benefit of congenital money, but are "liveable with"

when shared with like-minded folks. Enough about the boring subject of

money...it's a toy, it costs, you know the score ! |