As

the Air France charter Boeing 707-328 taxied from the terminal at Orly

Airport in Paris, France the crew began its pre-flight check. The Air

France jet known at "Chateau de Sully" had been chartered for a long

haul flight back to the Gateway City after the highly successful tour of

the Atlanta Art Association. On board were 122 passengers and a 10

member flight crew.

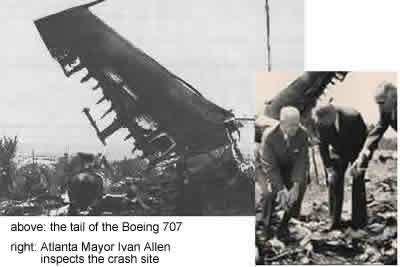

A Boeing 707

Ivan Allen, who had only recently become mayor, officially said goodbye

to 106 art patrons in early May, 1962. He did not know it, but he was

saying goodbye to these "lifelong friends" for the last time. For nearly

a month the cream of Atlanta society paid homage to the beautiful art of

Europe. Culmination of the Art Association Paris tour was a visit to the

Louvre, where the group saw paintings by Rembrandt, Raphael, da Vinci,

and an icon of American art -- "Whistler's Mother." From Paris they

journeyed to the Old World art centres that had long made Europe an

American tourist destination. It had been a good trip -- much

significant artwork, antiques and artefacts had been purchased, mostly

for the private collections of the individuals or as gifts for friends.

Orly Airport as it appeared in 1962

They returned to Paris from Rome on June 2, heading for famous Orly

Airport south of the city along the River Seine on the following day for

a late morning meal and then departure. The plane would fly from Paris

to New York's Idlewild Airport (it was later renamed to JFK

International), then on to Atlanta.

As the

pilot began his take-off roll down Runway 8, he maintained the runway

centre without a problem. At roughly 6000 feet (1800 meters), the plane

began lift-off. It was at this point that the pilot realized something

was wrong. According to witnesses, the nose of the aircraft rose from

the runway, but the body of the jet remained on the ground. Unknown to

the pilot at the time a motor that controlled the trim failed: there was

no choice but to abort take-off.

One goal

in this type of situation is to maintain the aircraft on the paved

runway. Unfortunately, most of the 10,700 foot runway 8 had been

expended as the 10, 000 pound thrust Pratt and Whitney engines powered

up for take-off. The Chateau de Sully would have to come to a stop in

less than 3000 feet.

Immediately, the pilot tried to lower the speed through braking. The

tires evaporated as he began to raise his flaps to decrease his speed

(braking by itself would not have stopped the aircraft). The plane

angled slightly to the left but skill kept the hurtling aircraft on

runway. Then came a harder move to the left as the Boeing jet approached

the edge of the pavement. The plane twisted right as the struggling

pilot tried to gain control of the aircraft, possibly attempting a

manoeuvre know as a "ground loop" during the rapid deceleration.

After the

tires were gone, the bare metal rims gouged deep ruts into the tarmac.

Finally the heavy gauge steel could no longer stand the stress and they,

too collapsed. About this time the 707 crossed into a grassy field at

the end of the runway. The plane bounced on the uneven ground as the

pilot continued his battle to control the aircraft. 300 feet after the

plane left the runway its left undercarriage broke off and fell to the

ground.

Still, an

open field lay in front of the pilot, and there might be a chance he

could avoid both the substantial landing lights and the small stone

cottage that lay between the aircraft and the River Seine, if he was

lucky. But time had run out. As the plane crossed the access road that

formed the perimeter of Orly Airport, the number 2 engine (on the left

side) broke into flames. Jarring blows from the uneven ground loosened

the engine, which dragged the plane to the left, into the landing lights

the pilot had tried to avoid. Down went the engine followed by what

remained of the landing gear, bursting into flames as the aircraft began

to disintegrate.

At the

point where the land begins a steep decline to the Seine the only major

piece still intact was the fuselage, the part holding the passengers and

flight crew. Down the slope it sped towards the Seine, striking the

empty stone cottage. The fuselage was consumed in a fireball, breaking

into pieces.

Of the

132 people on-board the Chateau de Sully, 129 died immediately. Two

stewardesses lives were spared: they were in their seats in the tail

section, which broke off before the plane struck the cottage, and walked

away from the crash. A third stewardess, who had also been in the tail

section died shortly after being rescued. Only the mid-air 1960 crash of

a TWA Constellation and a United DC-8 over New York City had taken more

lives (134)

Atlanta

struggled to deal with the loss. Life came to a standstill as the

Gateway City mourned its dead. The suits resulting from the accident

were adjudicated in the U. S. Court system and represented the largest

settlement from a single accident at the time. From the ashes of the

Chateau de Sully rose a lasting memorial to the men and women who died

on the aircraft. The people of the city of Atlanta gave the Woodruff

Arts Centre in memory of their fallen comrades.