structural failure in aircraft

By John Thorpe, GASCo's Chief

Executive

reproduced from GASCO

Pilots hope, trust and expect that this is an exceedingly rare event

because it is generally sudden and almost always catastrophic. In my early

days in Flight Test at Filton we had a number of Vickers Valiant V bombers

on a modification and upgrade programme. Each aircraft had to be flight

tested afterwards to make sure all was in order. Generally two flight

observers went along in the three rear facing seats, something I have

never got used to as it is alien to humans who have evolved over many

generations to face the way they are going, ever since they got on a

horse! My last Valiant flight was in the hands of a pilot who finished

with a tower flypast and steep climbing turn with four Avons disturbing

the peace and the tin-worms holding hands for grim death. Little did we

know - a couple of weeks later all Valiants were grounded due to the

discovery of one with near failure of the main wing spar. The ones at

Filton were summarily chopped up: some had only flown 400 hours.

Valiants being broken up at Filton in 1965

In

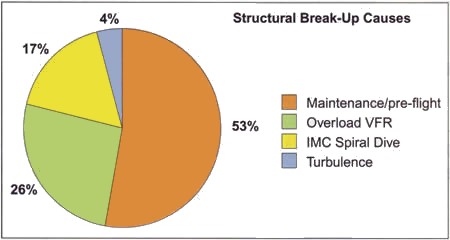

a recent 20-year period, there were 23 fatal accidents where

airframe/structure failure was a factor, 8% of the total. There were a

number of causes including maintenance/pre-flight (12 cases), overload VFR

(6 cases), death spiral in IMC (4 cases) and turbulence (1 case).

All

aircraft have specific limits on the amount of normal operational 'g' that

the structure will withstand before it is permanently deformed with a

further safety factor on top before failure occurs. Exceed these limits at

your peril. They can be exceeded in the very severest turbulence, during

badly executed aerobatic or spin manoeuvres particularly if the cg is

outside the correct range leading to over-light controls. Another event

that easily and frequently leads to airframe failure is loss of control in

IMC, either entered deliberately or inadvertently leading to the dreaded

death spiral. In the US, which has many more fatal accidents than the UK,

certain fast slippery aircraft have a reputation for this including the

Beech V tail Bonanza and the Mooney M20.

So how can such catastrophic events be avoided?

• Obviously know what the limits are for your particular aircraft and if

it is cleared for even limited aerobatics, make sure a 'g' meter is

fitted. Get aerobatic training from a qualified instructor, don't be

tempted to just 'have a go' like the pilot of a Rallye who managed to

wrinkle the wings when he exceeded the normal limit. It needed expensive

new wings, much to the Club's displeasure. Read Safety Sense Leaflet No 19

'Aerobatics'.

Wrinkled wings on Rallye 110S7after untrained pilot attempted aerobatics

•

Stay away from areas where unusually severe turbulence might be expected

such as the lea of mountains and cliffs in windy conditions, or the

vicinity or interior of a thunderstorm.

A Cuby fuselage minus wings after meeting severe coastal turbulence near

the Giant's Causeway, Antrim

•

If you fly a slippery aircraft and your licence allows you to fly in cloud

- slow down, it will give more time to deal with a minor upset and

probably keep you at less than Va, the speed at which all control surfaces

can be fully used. If you are a VFR pilot, stay out of cloud and if you

have an IMC Rating it is to get you out of trouble and is NOT the same as

an Instrument Rating.

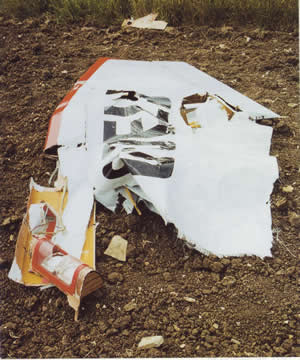

Fuselage of a PA-28R Cherokee Arrow on the South Downs near Amberley

following loss of control in IMC

•

If the aircraft has to be rigged before flight, check and double check,

don't hurry and don't let anyone distract you.

• Don't skimp on maintenance, especially potentially difficult inspection

of the slowly corroding structure, particularly if the aircraft lives near

the coast. The average age of the UK fleet is getting steadily older.

Remember that even a minor brush between a wingtip and the hangar door or

a straw bale can exert tremendous leverage on the centre section

structure. Satisfactory checking of composite aircraft may not be

straightforward.

Robin DR400 Regent wing near Almonsbury,

Gloucestershire which detached following an

earlier collision with a straw bale when

landing at Kemble

Don't

skimp on maintenance, especially potentially difficult

inspection of the slowly corroding structure

|