cold weather flying

aircraft preparation

During the pleasant days of summer, items of equipment may have

'disappeared'. Make sure the aircraft has serviceable pitot head covers,

static vent plugs, control surface locks and, if parked outside, proper

tie- downs. Having made sure you have got them – use them.

Some engines may need the aircraft manufacturer's approved winter cooling

restrictor to allow the oil and cylinders to reach and maintain correct

operating temperatures. After fitting, keep an eye on the oil

temperature/cylinder head temperature, especially if the weather turns

warmer.

The grade of engine oil may need to be changed when operating in colder

conditions. Consult the Manufacturers Manual or Maintenance Organisation.

Check that the cabin heater/demister is working properly before you

really need to use it. A faulty cabin heater, either combustion or

exhaust, can allow exhaust gases, including carbon monoxide, into the

cabin. If in doubt, have the heater pressure-tested. Carbon monoxide is

colourless, odourless, tasteless, insidious in its effects and lethal.

One of the first symptoms may be a severe headache, drowsiness or

dizziness.

‘Spot’ type carbon monoxide detectors only have a limited life when

unwrapped. Use a ‘fresh’ one and read the instructions.

The pitot-static system should be checked for water which can freeze and

block the system. If static drains are fitted, know where they are and

how to use them.

The battery is worked harder in winter, so make sure it is in good

condition and well charged. If you’ve had to make prolonged attempts to

start the engine, when it does start allow plenty of time for the battery

to re- charge before using heavy electrical loads. In a single-engined

aircraft it's all you are left with if the electrical charging system

fails in flight.

Some aircraft require the addition of Iso-propyl alcohol in the fuel for

operation in low ambient temperatures.

Check that all the airframe, propeller and windscreen systems are

operating correctly. De- icing systems suffer from neglect and may prove

faulty when required. Leaks may have developed in inflatable boots

especially on the tailplane (due to stones thrown up by the landing

gear/propellers), so check that they ALL inflate properly.

Make sure engine

crankcase oil breather pipes are clear and free from deposits which can

freeze, causing a pressure build-up that could force engine oil seals out

of their housings.

Control cable tensions may need to be adjusted.

flight preparation

If you are planning to visit another aerodrome, make sure it is open.

Mud, snow, flooding or frozen ruts may have necessitated closure.

Remember also that daylight and airport operating hours are much shorter

in winter.

Never fly in icing conditions for which the aircraft is not cleared. Do

not be misled into thinking that because an aircraft is fitted with

de-icing, or anti-icing, equipment, it is necessarily effective in all

conditions. Most general aviation aeroplanes are not cleared for flight

in icing conditions, although some protection may be given. Those cleared

are generally cleared only for flight in light icing conditions (the

equivalent of a build-up of 12 mm (1/2 inch) of ice in 40 nautical

miles). General aviation helicopters are not cleared. (See Pilots'

Operating Handbooks, Flight Manuals, etc.)

Continued flight into bad weather is the number one killer in

general aviation. Get an up to date aviation weather forecast.

The most likely temperature range for airframe icing is from 0 to –10° C;

it rarely occurs at –20° C or colder. Pay attention to any icing

warnings. Note the freezing level, it can be surprisingly low even in

Spring and Autumn; you may need to descend below it to melt an ice

build-up; but beware of high ground. Remember also that altimeters

over-read in very low air temperatures, by as much as several hundred

feet. You can be lower than you think.

If you are likely to encounter ice en- route, have you room to descend to

warmer air? Will the airspace or performance allow you to climb to cold,

clear air? (Note that any ice build up may not melt and will degrade

cruise performance). Can you land safely at your destination? If the

answers to these questions are NO, don’t go.

Prepare an accurate route plan with time markers, including an

alternative in case you do encounter ice/snow. The countryside looks very

different when covered by a blanket of snow and familiar landmarks may

have disappeared.

Wet snow, slush or mud can seriously lengthen the take-off run or prevent

take-off altogether. Check the Flight Manual and Aeroplane Performance,

and allow a generous safety margin, especially from grass.

Have a cloth handy for de-misting the inside of the windows while

taxiing.

Dress sensibly, (you should spend some time outside whilst pre-flighting

the aircraft), and have additional warm clothing available in case of

heater failure or a forced landing.

Some parts of the the country will be pretty inhospitable in winter so,

if you are in a single-engined aircraft, file a flight plan and carry a

few survival items in case of a forced landing, e.g. warm clothing,

silvered survival bag, torch/ mirror and whistle for signalling.

Be prepared to divert and carry a night- stop kit. Don't put pressure on

yourself to get home if the weather deteriorates.

When snow has fallen, check SNOWTAMS in the NOTAM series, if available,

to find out if your proposed destination, and alternate(s), are open and

which operational areas have been cleared. If there is an eight digit

code at the end of a METAR, it shows that winter conditions affect that

aerodrome. It may be easiest to telephone them. The first two digits, of

the eight digit code, are the runway and the last two the braking action.

Know the effect that braking action described as, for example POOR, will

have on the landing/abandoned take-off distance you need to have

available. Bear in mind the effects of a crosswind combined with an icy

runway.

pre-flight

There may be a greater risk of water condensation in aircraft fuel tanks

in winter. Drain fluid from all water drains (there can be as many as

thirteen on some single-engined aircraft). Drain it into a clear

container so that you can see any water.

When refuelling, ensure

the aircraft is properly earthed. The very low humidity on a crisp, cold

day can be conducive to a build-up of static electricity.

After flying high such that integral wing tank fuel has been ‘cold

soaked’, and the ambient air is humid and cool, frost will form. If it is

raining, almost invisible clear ice may form.

Tests have shown that frost, ice or snow with the thickness and surface

roughness of medium or coarse sandpaper reduces lift by as much as 30%

and increases drag by 40%. Even a small area can significantly affect the

airflow, particularly on a laminar flow wing.

Ensure that the entire

aircraft is properly de-iced and check visually that all snow, ice and

even frost, which can produce a severe loss of lift, is cleared. This

includes difficult-to-see ‘T’ tails. If water has collected in a spinner

or control surface and then frozen, this produces serious out-of-balance

forces. There is no such thing as a little ice.

The most effective equipment for testing for the presence of frost and

ice are your eyes and your hands.

The best way to remove snow is by using a broom or brush. Frozen snow,

ice and frost can be removed by using approved de-icing fluid in a

pressure sprayer similar to a garden sprayer. An alternative is to melt

the ice with hot water and then leather the aircraft dry to prevent

re-freezing. Make sure that control surface hinges, vents etc are not

contaminated. A scraper might damage aircraft skins and transparencies.

Do not rely on snow blowing off during the take off run. The ‘clean

aircraft concept’ is the only way to fly safely – there should be nothing

on the outside of the aircraft that does not belong there.

Check that the pitot heater really is warming the pitot head – but don't

burn your hand (use the back of it) or flatten the battery.

Beware of wheel fairings jammed full of mud, snow and slush –

particularly mud, as it is dense and doesn't melt (on one occasion 41 kg,

nearly 100 lb, of mud was removed from the three wheel fairings of a 4

seat tourer). If the fairings are removed, there may be a loss of

performance and removal may invalidate the aircraft's C of A. Check that

retractable gear mechanisms are not contaminated. Also, remove mud from

the under-side and leading edge of wings and tail plane; it seriously

affects airflow.

Water-soaked engine air intake filters can freeze and block the airflow.

If hand-swinging a propeller, perhaps because of a flat battery, move the

aircraft to a part of the airfield which isn’t slippery. Don’t try it

unless you’ve been trained. Use chocks and a qualified person in the

cockpit.

During the engine run-up, check that use of carburettor heat gives a

satisfactory drop in rpm or manifold pressure.

Check any de-icing boots,

particularly the tailplane, for condition, holes etc. Wiping the boots

with approved anti-icing fluid will enhance their resistance to ice build

up.

departure

Remember that taxiways and aerodrome obstructions may be hidden by snow,

so ask if you are not certain.

Check the cabin heater/demister operation as early as possible. Be

prepared to use the DV window.

Taxi slowly to avoid throwing up snow and slush into wheel wells or onto

the aircraft's surfaces. Taxiing slowly is safer in case the tyres slide

on an icy surface. Stop well clear of obstructions if there is any doubt

about braking effectiveness.

Allow gyro instruments extra time to spin-up when they are cold.

You may consider using a 'Soft Field' take off technique – if so be sure

that you are fully aware of recommended procedures.

Ensure that no carburettor ice is present prior to take-off by carrying

out a 15 second carb heat check, both during power checks and before

take-off. Ensure the engine is developing full power before taking off.

en route

After take-off on a slushy or snowy runway, select the gear UP-DOWN-UP.

This may loosen accumulated slush before it freezes the gear in the up

position.

Monitor VOLMET and turn back or divert early if the weather deteriorates.

Don't wait until you are in a blinding snowstorm or covered in ice.

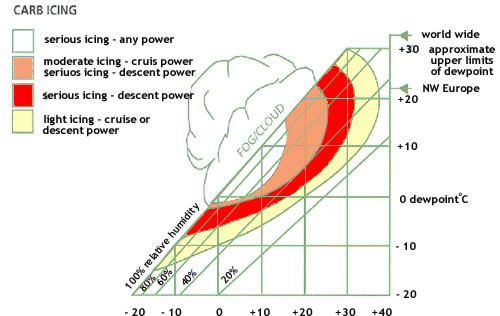

Carburettor icing is one of the worst enemies. The chart shows when it is

most likely to occur. (See also Leaflet No 14 – ‘Piston Engine Icing’.)

Carburettor ice forms stealthily, so monitor engine instruments for loss

of rpm (fixed pitch propeller) or manifold pressure (constant speed

propeller), which may mean carb ice is forming.

Apply full carb heat periodically (every 10-15 minutes) and keep it on

long enough to be effective. As a guide, carb heat should be applied for

a minimum of 15 seconds, or longer if necessary. The engine may run

roughly for a short period while the ice melts.

Use carb heat as an intermittent ON/ OFF control – either full hot or

full cold. Do not use carb heat continuously or at high power settings

unless the Handbook/Flight Manual allows it. At low power settings, eg

descent, the application of heat before reducing power, and its

continuous use while power is low, is recommended.

During a descent, when using small throttle openings, with full carb

heat, increase rpm periodically to warm the engine.

Remember carb heat increases fuel consumption.

At low rpm, use full heat but if appropriate cancel it prior to touchdown

in accordance with Manual/Handbook instructions.

In the absence of

dewpoint information assume high humidity when:

• the ground is wet (even dew)

• in precipitation or fog

• just below cloud base

If the aircraft has de-icing boots, it’s a good idea to cycle the boots

from time to time, even when ice is not expected. This prevents the

valves in pneumatic systems from sticking.

If you are flying just above clouds to stay clear of airframe icing,

remember that the cloud tops will quickly rise as you fly:

• across high ground;

• towards a warm, cold or occluded front;

• towards a low pressure area.

If you fly into the top of clouds, the concentration of water droplets is

often greatest near the cloud top and ice could build up quickly.

Airframe Icing is most frequently encountered within convective clouds,

Cumulus or Cumulonimbus (CU/CB) where the build up of ice can be very

rapid. In these clouds the icing layer can be several thousand feet thick

and a dramatic change of altitude will be required to avoid icing. It is

better to avoid flying through these clouds if you can, either by turning

back or changing your route.

Icing can also occur in thin layered clouds, especially during the

winter. During the autumn, winter and spring an extensive sheet of

Stratocumulus (SC) may frequently form just below a temperature

inversion, with the temperature in the cloud between 0 to –10° C. Such

clouds may only be one to two thousand feet deep but within the cloud

layer ice may build up quickly. This icing can be avoided by descending

below the cloud, provided there is sufficient height available above the

ground, or by climbing above the cloud layer.

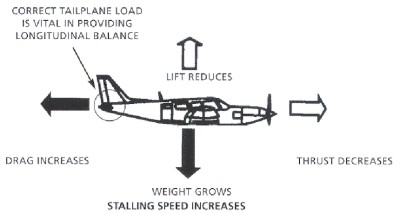

If you see ice forming anywhere on the aircraft, act promptly to get out

of the conditions, don’t wait until the aircraft is loaded with ice. Ice

forms easiest on thin edges. As the tailplane generally has a smaller

leading edge radius than the wing it means that if you can see it on the

wing, the tailplane (or propeller blades) will already have a heavier

load. Pilots have reported that ice builds up 3 to 6 times faster on the

tailplane than the wing and up to double that on a windshield wiper arm.

On some aircraft the tailplane cannot be seen from the cockpit. In fact

the pencil like OAT probe is often the first place ice forms. If ice does

form, keep the speed up; Don’t fly too slowly. The stall speed will have

increased. The Manual/Handbook may give a minimum speed to cope with

increased drag and weight due to ice build - up.

The stall warning system

may be iced up or otherwise affected. It is in any case designed and

calibrated to provide indication of wing stall, not the tailplane!

If you’ve got a big build-up of ice, the drag and weight are increasing

while the climb performance is decreasing so you can’t climb to get above

it. High ground may prevent you from descending.

Tell ATC so that others can be warned.

Most of the time snow, which is already frozen, will not stick to an

aircraft, but occasionally wet snow with a high moisture content will

stick. Treat it like ice.

Freezing rain can occur during the winter months either at or near the

ground, or in a layer above the ground. It occurs when warm moist air is

moving into a cold region. The invading warm moist air may cause a layer

of air, where the temperature is higher than zero° C, to overrun a much

colder layer beneath where the temperatures are below zero° C. Under

these conditions precipitation forming in the high cloud layers will melt

to form rain as it falls through the warm air which will then fall into

the sub-freezing layer beneath. This rain will quickly freeze again in

the cold air forming a solid layer of clear ice over everything. This

clear ice will build up very quickly and be difficult to ‘shake off’.

Freezing rain is the most severe form of airframe icing. It can be

encountered in flight up to altitudes of 10 000 feet, or it may be

encountered on the ground or when flying close to the ground. Aircraft

parked outside will be quickly coated with a layer of clear ice, and

similarly aircraft in flight. If such conditions are encountered in

flight near the ground it is best to land as soon as possible, or if the

severe icing is encountered at a higher altitude descend, if possible,

into a warmer layer below.

If you are in trouble, tell someone clearly and in good time and make

sure the transponder is ON and set to code 7700. The Emergency Services

can receive a transponder return much better than the primary radar

return.

Ice forming on an aircraft can cause odd vibrations and noises. An aerial

iced up may begin to vibrate (and can fall off). Don’t panic, remember

AVIATE, NAVIGATE, COMMUNICATE.

Monitor any autopilot, it may have been surreptitiously altering the trim

to compensate, possibly, for the effect of an ice build- up.

landing

If on arrival you descend with an iced up aeroplane and windshield and

cannot see, use the DV window.

Most icing accidents occur when the pilot loses control during approach

or landing. Even a thin coat of ice on the aircraft justifies a 20%

increase in approach speed. It will extend the landing run – perhaps on a

slippery runway. The handling may be different, don’t make large or

abrupt changes in power or flap settings.

If you suspect, because of changed stick forces or vibration, that there

is ice on the tailplane, a flapless or partial flap landing may be

advisable (the handbook/manual gives flapless-approach speeds). This

reduces the tailplane load and the likelihood of tailplane stall, which

can result in a VERY severe pitch down. Recovery is by REDUCING THE FLAP

angle and by pulling hard – over 50 kg (110 lbs) may be necessary.

Another unpleasant surprise due to tailplane ice could be when the

aircraft is being flown on autopilot, which has been slowly and silently

re-trimming nose-up and reaches the limit. When the flaps are lowered,

the autopilot could disconnect and it may require 4 strong arms to

recover. Again, go for the flap selector.

When landing on a very wet or icy runway, particularly in a crosswind,

the aircraft may aquaplane or slide and directional control can be lost.

In such circumstances an alternate runway or diversion is necessary.

Aircraft with castoring nosewheels may be more vulnerable.

Remember that ground

temperatures fall quickly during the late afternoon on an exposed

airfield and by dusk ice may be forming on any wet runways. The ice may

form as a clear sheet which is invisible and has a coefficient of

friction of zero!

Helicopter pilots should beware of 'white-out' due to blowing snow when

hovering.

after flight

Take care when getting out of the aircraft. Jumping from the aircraft

walkway onto an icy apron could lead to a painful tumble.

If parked outside, use control locks and proper tie-downs to guard

against winter gales. Face into the prevailing or forecast wind. Put

proper pitot and static covers on – make sure the pitot has cooled down!

If it is muddy or slushy, inspect wheel fairings, landing gear bays,

flaps and tailplane for loose mud or slush. These are easier to remove

when soft than when frozen.

Notify Air Traffic if the actual weather was different, or worse, than

forecasted. It might be important for other pilots to know.

summary

• Stay out of icing conditions for which the aircraft has NOT been

cleared.

• Note freezing level in the aviation weather forecast. Don’t go unless

the aircraft is equipped for the conditions.

• Have warm clothing available for pre- flight and in case of heater

failure or forced landing.

• Mud, snow and slush will lengthen take off and landing runs. Work out

your distances.

• Remove all frost, ice and snow from the aircraft – there is no such

thing as a little ice.

• Check carefully that all essential electrical services, especially

pitot heat, are working properly.

• Check that the heater/demister are effective. Watch out for any signs

of carbon monoxide poisoning.

• Be extra vigilant for carb ice.

• If ice does start to form, act promptly, get out of the conditions by

descending (beware of high ground), climbing or diverting.

• If you encounter ice, tell ATC so that others can be warned.

• During the approach if you suspect tailplane ice, or suffer a severe

pitch down, RETRACT THE FLAPS.

• If you have to land with an iced up aeroplane, add at least 20% to the

approach speed.

• Snow covered, icy or muddy runways will make the landing run much

longer and crosswinds harder to handle.

THERE IS NO SUCH THING

AS A LITTLE ICE

|