navigation

... the big picture

Irv Lee offers confidence for those

who find navigation an uncertain business.

reproduced from GASCO

Irv Lee works mostly out of Popham, which is an

unlicensed airfield that is the base for some 110 aeroplanes and

microlights and has a club with around 500 members. You will find it by

road or by air half a thumb south west of Basingstoke, ' just off the

A303. Why do I speak , in thumbs? Read on.

Irv is an experienced instructor who gave up a

successful career in IT to offer instruction and advice to pilots who

already have a PPL, but want to extend their experience and skills. You

may have encountered him as part of the Flying Doctor series in

Flyer magazine and full details of what he offers can be found on

www.higherplane.flyer.co.uk .

This article sprang from a chance conversation between

Irv and myself on the thorny issue of navigation. I asked Irv whether the

introduction by the CAA of a navigation leg in the requirements for a

revalidation or renewal test was causing any problems for PPLs. I asked

the question because on the

www.flyontrack.co.uk website

there is frequent discussion on how it is that PPLs keep busting control

areas with such sad regularity and why poor standards of navigation are so

common. I seemed to touch a sensitive spot here, and Irv reported that he

does encounter PPLs whose aircraft handling skills are fine, but whose

navigation is substandard. Can I use GPS?, was the question most

frequently put when a pilot discovered the new requirement for the

navigation leg.

In parenthesis, I should explain at this point that if

you are one of the many who revalidate their PPL by flying at least 12

hours in two years and take a flight with an instructor (a revalidation

flight) during that time, then that instructor may not seek to explore

your navigational ability. But if you are one of those' who, for all sorts

of reasons, needs a revalidation or renewal test, then you will

have to undertake the navigation leg and a fail in that will mean an

outright fail.

Whatever the regulations may require, it does seem to

Irv, and to me a sad state of affairs if there are many pilots amongst us

whose handling skills are good but whose navigation is too uncertain for

them to contemplate leaving their local area without the help of GPS. The

pages of this magazine are often filled with the forthright comments of

both the supporters and the decriers of GPS. Irv Lee is one of the

supporters but neither Irv nor any other supporter claims that pilots

should put all their trust in GPS and make no check of their navigational

progress by other means. For the VFR pilot 'other means' must almost

always mean visual navigation, that is to say, the techniques that we were

all taught in order to get our licences in the first place.

A lot of the problem, as Irv sees it, is that the

standard VFR navigation techniques - the whizzy wheel, the stop watch, the

compass and the map with its track and 5 degree and 10 degree off track

lines - leave many PPLs feeling defeated and confused. You study the Met,

you draw all those lines, you whiz the wheel and you end up with a heading

of 248 degrees and a time to the first checkpoint of 13 minutes. You fly,

as best as you can, 248 degrees for 13 minutes and there you are,

uncertain of your position again. You fly on for a further 5 minutes and

things get no better, so once again you sadly lament your failure as a

navigator and your utter reliance on your GPS set, whether it is right or

wrong.

Irv acknowledges that the classic VFR navigational

techniques, with all their absorbing detail, are meat and drink for some

PPLs. Their plots before the flight are masterpieces of intricacy and

their flight logs after the flight are miniature copy books, straight out

of a manual of navigation. For others, however, the flight log ceases

somewhere about the first checkpoint as the pilot searches in vain for the

cross between a river and a railway line that should have appeared. Four

minutes after the ETA has passed that pilot eventually comes across a

river and railway line cross, seizes on this without further checking and

steams off on the next section into the even more unknown. At that point,

as confusion and tension heighten, any further attempt to maintain a log

is abandoned.

If your own navigation sounds more like the second

version above, take heart. It may be that the classic technique is not

really for you and you need to try something along the lines of Irv Lee's

Big Picture navigation. If this sounds like an easy cop out for

simpletons, take heart. A millennium or so ago, I was taught something

very similar in the RAF. They called it Pilot Nav, and they argued that

someone hurtling around the sky in a single seater would have neither the

time nor the inclination to dwell upon the minutiae of navigation and so

they made us simplify the whole procedure and, in effect, to think mostly

about what Irv now calls the Big Picture.

A more defining title for this method might be termed,

When Airborne, Approximate and Simplify. So you do all the pre

flight planning and preparation as you have always done, but in the air

you concentrate on the Big Picture and avoid too much confusing detail.

For example, your whizzy wheel commanded a heading for the first leg of

248 degrees, but consider in practice, what this will mean. If you set out

on a heading of 248 degrees, how closely will you actually fly to this

figure, assuming that you will also be dealing adequately with all the

other tasks of the flight? You will do well to end up averaging a heading

of anything between 245 and 250 degrees.

And how did you arrive at this magical figure of 248

degrees in the first place? Well you fed into the whizzy wheel a True Air

Speed (TAS) figure whose accuracy much nearer than, say, two or three KTS

either way must be questionable. Worse, you fed in a forecast wind, but

how confident are you that the actual wind has turned out the same as was

forecast?

"Life's too short", says Reggie Bender, "to phone 0500 354802 before take

off "

So, after allowing for vagaries in your heading keeping

ability, the variations from your plot figures of TAS and wind speed and

your invariable failure to apply the compass deviation shown on the card

near your aircraft's compass (does anyone?), you cannot regard that 248

degrees as anything more than an approximation anyway, no matter how much

care you may have put into its original calculation. So the Big Picture is

that you are setting out on your first leg on a roughly WSWIy heading

which should take you roughly in the direction of the first check point

but do not imagine that the features that lie along your carefully drawn

track line are going to pop up, one by one, as the flight proceeds. Look

upwards, Big Picture pilot, if not to the skies, then at least towards the

horizon and navigate as much by what you see there as by what lies

directly beneath.

The smart new Pilots' Briefing Room at Popham.

There's a range of hills coming up on your right in the

middle distance and that must be the Quantocks, there's a whole lot of

flat countryside beneath with no particular features but on this heading

you will meet the M5 before long and will then be able to identify

Bridgwater or Taunton. So meanwhile, although you cannot tell precisely

where you are, you know where you are going, so you will stick to your

heading, keep scanning the horizon for more clues (the Bristol Channel

coastline?, the Blackdown hills?) and expect to cross the M5 in six

minutes time. If you cannot see it in three minutes, something will be

amiss and you will have to take action (e.g. climb in a circle while

looking for more clues, seek help from Yeovilton LARS, or call Distress

and Diversion on 121.5 - they genuinely welcome a little challenge).

Meanwhile, you should just check that six minutes to the MS estimate.

Refer back to the last definitely known position (that's 'definitely', not

`probably') and apply Irv Lee's Rule of Thumb.

Your typical six minute thumb aeroplane. (W J Bushell)

Irv Lee's Rule of Thumb is both simple and effective.

It says, quite simply, that, with neither headwind nor tailwind, you fly

across the map at the rate of 6 minutes per thumb. How does he know that?

Because as well as having a degree in Aeronautical Engineering, he can do

simple arithmetic. Your average light aeroplane cruises between 90 and 110

KTS and your average thumb's knuckle to tip measures about 10 n.m. on a

half mill map. 10 n.m. is about one tenth of the amount the average light

aeroplane does in an hour and one tenth of one hour is six minutes. Irv's

case rests: in no wind one thumb equals six minutes.

Sticklers for accuracy can make their own adjustments

to this Rule to match their own particular thumb/aeroplane combination and

we must all have our own still air thumb time to start from. A large

thumbed goalkeeping giant flying a flexwing might have an 12 minute thumb,

while a small thumbed petite lady flying a Columbia 400 might have a three

minute thumb but for most of us it is going to be pretty close to six

minutes.

That's all very well for the no headwind or tailwind

situation but for most of the time we have that factor to take into

consideration. Here's how a Big Picture navigator works out the effect of

a headwind or tailwind once airborne. You start with the forecast wind:

let's say it is 280 deg/ 20 KTS. If your heading is 248 deg, the wind is

about 30 deg off the nose. Common sense tells you that if the wind is in

exactly the same or in exactly the opposite direction as your heading, you

must apply all of the wind as your headwind or tailwind component. As for

other wind directions, you must either commit the next bit to memory or

write it down on your knee pad:

If the wind is

45 deg off your heading, allow three quarters of the wind for your

headwind/tailwind component and if

it is 60 deg off, allow half. Interpolate (i.e. make a rough guess) for

anything else.

These fractions are not absolutely accurate (but then,

nor is the forecast wind) but they are near enough for Big Picture nav. So

in the case in point, we are looking at nearly 20 KTS of headwind, in

which case our ground speed is going to be around 80 KTS and one thumb

will then represent 10/80 ths (one eighth) of an hour, or 60/8 minutes, or

7Yz minutes. If you want to devise a table of thumb distances for

different ground speeds, you can, but you might well do better to keep

things simple and to just reckon that if you have a substantial headwind

on a leg, your minutes per thumb are going to be a fair bit more than the

standard six: say, seven or eight minutes in this case.

A thumb will be worth more than six minutes in this one. (W J Bushell)

Are you getting the idea? When airborne you deal all

the time in approximations and in that way you keep yourself in touch with

what is really going on in practice, and you don't bother much about the

theory. Always consider what the wind is doing to you and what the

appropriate number of minutes per thumb should be on each leg.

Drift is the other issue to consider. A 100 KTS

aeroplane suffers 3 deg maximum drift for every 5 KTS of crosswind. So a

10 KTS crosswind will give 6 deg maximum drift and 20 KTS will give 12

deg. That works just fine for a crosswind blowing at 90 deg to our

heading, but what about crosswinds from other directions? In our example,

the wind is 20 KTS, so that could cause drift up to a maximum of 12 deg,

depending on the wind's direction in relation to our heading.

This is the Rule:

Allow half of the maximum crosswind at 30 deg off and

all at 60 deg off or more. Interpolate in between.

Again, these are only approximate figures but they are

good enough for the Big Picture.

The maximum drift from our 20 KTS wind is 12 deg and our 280/20

wind is blowing at 30 deg to our 248 deg heading. We must allow half of

the maximum for a 30 deg crosswind so we must allow 6 deg. So lets try

that again with a wind this time of 145/25 on our 248 deg heading.

The wind direction is 100 deg less than our heading, so

that means that there is virtually no tailwind component and our thumb

will represent six minutes on this leg. At 3 deg max drift per 5 KTS of

crosswind the 25 KTS crosswind will create 15 deg max drift. The crosswind

is well over 60 deg off - nearly 90 deg in fact - so we take the maximum

of 15 deg and we steer, say, 235 deg (once airborne, life's too short to

worry about intervals of less than five degrees).

So that is all that you need to know about time and

drift. Of the two, time is probably the more important. Unconfident pilots

usually manage to fly within a reasonable corridor along the planned

track, even if they fail to identify any part of the terrain beneath at

times. (They would be wise, in any case, to look out for any features

within, say, 10 n.m. of the track line and thus allow for a bit of

wandering from track.) However, they can easily become fixated on just

sticking to their heading, sometimes well after the ETA for the next

waypoint, in the forlorn hope that the waypoint is going to appear

magically at last. So be disciplined about your ETA and if the waypoint

fails to appear on time, do something positive.

Always consider

what the wind is doing to you and what the

appropriate number of minutes per thumb should be on each leg.

Irv Lee's Higher Plane seminar takes a whole day and

navigation is only a part of it. This is not the time to stray into other

issues, but here are two that have an important bearing on navigation and

should therefore be mentioned.

The first is the forecast wind. Most pilots use Metform

214 as their source of information here and tend to regard its word as

gospel. Excellent as our Met Office is, their Metform 214 needs the

application of some caution before using any wind forecast. Looking at the

spot wind forecast at 0845Z today for the winds between 0600 and 1200, I

see that the nearest box is forecasting a 2,000 ft wind of 270/10. So if I

am going to make my flight later this morning, that is the wind I should

use. Or is it? Consider some other factors: the next nearest box, not much

further away than the nearest, shows VRB/10. The forecast is dated 0312Z

so by 1200Z the forecast will be nine hours old, and an awful lot can

happen to our British weather in nine hours, some of it sometimes

unforetold.

Still a six minute thumb for this one - but all three thumb sections in

this case. (via W J Bushell)

Irv Lee therefore counsels a reality check before take

off. Find out what is the surface wind at your departure airfield. Do you

recall that during the day the 2,000 ft wind is usually about 30 deg more

and is double the strength of the surface wind, less 10 per cent? Apply

those figures to the current surface wind and compare the result with your

forecast wind. If they differ significantly, then ignore the forecast wind

and use your new calculated actual wind; it will be far more accurate.

As you fly your route, do not imagine that the 2,000 ft

wind will necessarily remain constant but put your faith in observation of

the wind effect on the first thumbful of each leg. That is the most

accurate forecast wind that you will ever get, and you don't have to make

all those theoretical calculations, you just observe that this leg is

giving you a five and a half minute thumb and a bit of drift to the right.

Find out what is the

surface wind at your departure airfield.

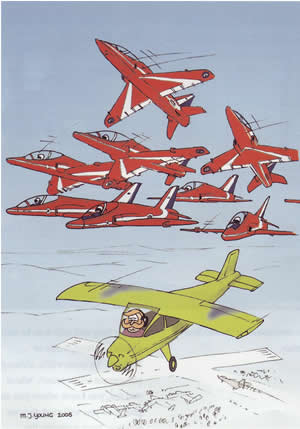

The final issue is NOTAMs. Getting hold of NOTAMs can be

difficult and deriving useful, relevant and practical information from

them can be even more so. Consequently an awful lot of pilots do not even

try. The result of busting a Temporary Restricted Airspace (a TRA is

usually a Royal Flight) could be bad enough but what might happen if you

were to find yourself in the middle of a Red Arrows display scarcely bears

thinking about. Nonetheless 14 hapless pilots have bust Red Arrows

displays in the past three years. Fortunately there have been no mid airs

so far, although several PPLs have been severely punished. Irv's point is

simple: while there may be some rather unconvincing excuses for not

getting and understanding NOTAMs there can be absolutely no excuse for

not, at least, phoning 0500 354802 for information on TRAs and Red Arrows

displays on that day. It's free, it takes only about a minute, and pilots

who cannot be bothered at least to make this simple check before take off

will have few friends if their idleness leads to a Red Arrows bust.

|