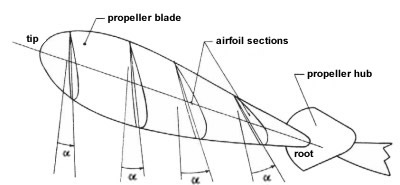

fig 6 - 4 cross section of a propeller. An a (alpha) denotes angle of attack of

airfoil sections

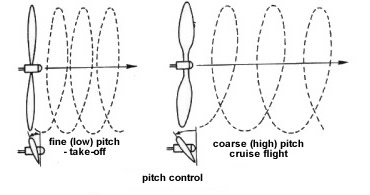

Propellers may be classified as to whether the blade

pitch is fixed or variable. The demands on the propeller differ

according to circumstances. For example, in takeoffs and climbs more power

is needed, and this can best be provided by low pitch. For speed at

cruising altitude, high pitch will do the best job. A fixed-pitch

propeller is a compromise.

fixed

pitch propellers

The propeller is made in

one piece. Only one pitch setting is possible and is usually two blades

propeller and is often made of wood or metal.

Wooden Propellers:

Wooden

propellers were used almost exclusively on personal and business aircraft

prior to World War II .A wood propeller is not cut from a solid block but

is built up of a number of separate layers of carefully selected .any

types of wood have been used in making propellers, but the most

satisfactory are yellow birch, sugar maple, black cherry, and black

walnut. The use of lamination of wood will reduce the tendency for

propeller to warp. For standard one-piece wood propellers, from five to

nine separate wood laminations about 3/4 in. thick are used.

Metal Propellers:

During 1940, solid steel propellers were made for military use. Modern

propellers are fabricated from high-strength , heat-treated, aluminium

alloy by forging a single bar of aluminium alloy to the required shape.

Metal propellers is now extensively used in the construction of propellers

for all type of aircraft. The general appearance of the metal propeller is

similar to the wood propeller, except that the sections are generally

thinner.

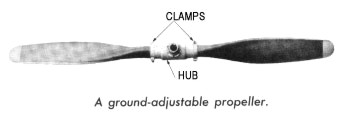

variable pitch propellers

There are two types of

variable-pitch propellers adjustable and controllable. The adjustable

propeller's pitch can be changed only by a mechanic to serve a particular

purpose-speed or power.

The variable pitch propeller

permits pilots to change pitch to more ideally fit their requirements at the

moment. In different aircraft, this is done by electrical or hydraulic means.

Two-position: A propeller

which can have its pitch changed from one position to one other angle by the

pilot while in flight.

Controllable pitch: The

pilot can change the pitch of the propeller in flight or while operating the

engine by mean of a pitch changing mechanism that may be operated by

hydraulically.

Constant speed

propellers

In modern aircraft, it is done

automatically, and the propellers are referred to as constant-speed

propellers. As power requirements vary, the pitch automatically changes,

keeping the engine and the propeller operating at a constant rpm. If the rpm

rate increases, as in a dive, a governor on the hydraulic system changes the

blade pitch to a higher angle. This acts as a brake on the crankshaft. If the

rpm rate decreases, as in a climb, the blade pitch is lowered and the crankshaft

rpm can increase. The constant-speed propeller thus ensures that the pitch is

always set at the most efficient angle so that the engine can run at a desired

constant rpm regardless of altitude or forward speed.

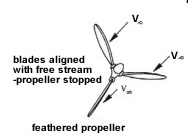

Constant-speed propellers may

have a full-feathering capability. Feathering means to turn the blade

approximately parallel with the line of flight, thus equalizing the pressure on

the face and back of the blade and stopping the propeller. Feathering is

necessary if for some reason the propeller is not being driven by the engine and

is wind-milling, a situation that can damage the engine and increase drag on the

aircraft.

Some controllable-pitch and

constant-speed propellers also are capable of being reversed. This is done by

rotating the blades to a negative or reverse pitch. Reversible propellers push

air forward, reducing the required landing distance as well as reducing wear on

tires and brakes.

Beta Control: A propeller

which allows the manual repositioning of the propeller blade angle beyond the

normal low pitch stop. Used most often in taxiing, where thrust is manually

controlled by adjusting blade angle with the power lever.

Propeller theory

The forces.

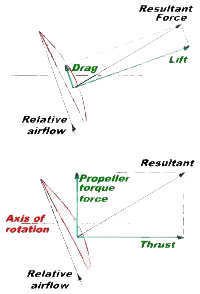

Propeller blades are constructed using aerofoil sections to produce an

aerodynamic force, in a similar manner to a wing. Consequently the blades are

subject to the same aerodynamics – induced drag, parasite drag, wingtip

vortices, lift/drag ratios at varying aoa, pressure distribution changing with

aoa etc. There is a difference in application because, in flight, the propeller

has rotational velocity added to the translational [forward] velocity thus the

flight path of any blade section is a spiral – a helical flight path.

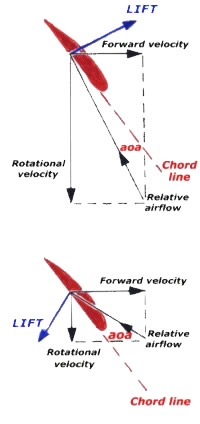

The diagram at left represents a blade section in flight and rotating around the

shaft axis. Because of the different application it doesn't serve much purpose

to express the resultant aerodynamic force as we would for a wing, with the

components acting perpendicular (lift) and parallel (drag) to that flight path,

as in the upper figure. So we represent the aerodynamic force component acting

forward and aligned with the aircraft's longitudinal axis as the thrust force,

and that component acting parallel to the direction of rotation as the propeller

torque force.

As you see in the lower figure the component of the lift acting in the

rotational plane has now been added to the drag to produce the 'propeller torque

force' vector. The remaining forward acting portion of lift is then the thrust.

That is why propeller efficiency is usually no greater than 80 – 85%, not all

the lift can be used as thrust and the propeller torque force consumes quite a

bit of the shaft horse power. The propeller torque and the engine torque will be

in balance when the engine is operating at constant rpm in flight.

There are other forces acting on the blades during flight, turning moments that

tend to twist the blades and centrifugal force for example. The air inflow at

the face of the propeller disc also affects propeller dynamics.

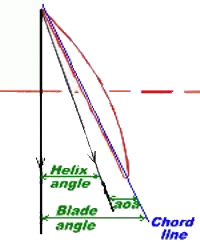

Blade angle and pitch

Although all parts of the

propeller, from the hub to the blade tips, have the same forward velocity, the

rotational velocity – and thus the helical path of any blade station – will

depend on its distance from the hub centre. Consequently, unless adjusted, the

angle of attack, will vary along the length of the blade. Propellers operate

most efficiently when the aoa at each blade station is consistent (and, for

propeller efficiency, that giving the best lift drag ratio) over most of the

blade, so a twist is built into the blades to achieve a more or less uniform aoa.

The blade angle is the

angle the chord line of the aerofoil makes with the propeller's rotational plane

and is expressed in degrees. Because of the twist the blade angle will vary

throughout its length so normally the standard blade angle is measured at the

blade station 75% of the distance from the hub centre to the blade tip. The

angle between the aerofoil chord line and the helical flight path (the relative

airflow) at the blade station is, of course, the angle of attack and the angle

between the helical flight path and the rotational plane is the angle of advance

or helix angle. The aoa and helix angle vary with rotational and forward

velocity.

The basic dimensions of propellers for light aircraft are usually stated in the

form of number of blades, diameter and pitch with the latter values given in

inches. e.g. 3 blade 64" × 38". The pitch referred to is the geometric pitch

which is calculated, for any blade station but usually the 75% radius position,

thus:

Geometric pitch = the circumference (2 π r) of the propeller disc at the

blade station multiplied by the tangent of the blade angle. Thus it is the

distance the propeller – and aircraft – would advance during one revolution of

the propeller if the blade section followed a path extrapolated along the blade

angle.

e.g. For a blade station 24 inches from the hub centre [0.75r] and a 14° blade

angle, the circumference = 2 × 3.14 × 24 = 150 inches and tangent 14° = 0.25.

Thus the geometric pitch is 150 × 0.25 = 38 inches. Propellers are usually

designed so that all blade stations have much the same geometric pitch.

Designers may establish the ideal pitch of a propeller which is the

theoretical advance per revolution which would cause the blade aerofoil to be at

the zero lift aoa; thus it would generate no thrust and, ignoring drag, is the

theoretical maximum achievable aircraft speed.

The velocity that the propeller imparts to the air flowing through its disc is

the slipstream and slip used to be described as the difference

between the velocity of the air behind the propeller ( i.e. accelerated by the

propeller) and that of the aircraft. Nowadays slip has several interpretations,

most being aerodynamically unsatisfactory, but you might consider it to be the

difference, expressed as a percentage, between the ideal pitch and the advance

per revolution when the the propeller is working at maximum efficiency in

conversion of engine power to thrust power. Slip in itself is not a measure of

propeller efficiency; as stated previously propeller efficiency is the ratio of

the thrust power (thrust × aircraft velocity) output to the engine power input.

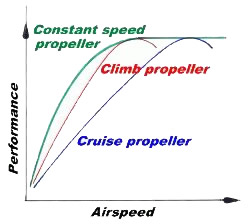

Pitch and velocity

The performance of aircraft

fitted with fixed pitch or ground adjustable propellers is very much dependent

on the chosen blade angle. Fixed pitch propellers limit the rpm developed by the

engine at low forward velocity, such as occurs during the take-off ground roll

and may also allow the engine rpm to exceed red-line maximum when the load on

the engine is reduced, such as occurs in a shallow dive. Fixed pitch propellers

operate at best efficiency at one combination of shaft power and airspeed. Blade

angle is usually chosen to produce maximum performance at a particular flight

condition, for example:

• Vy climb i.e. a climb propeller

• Vc cruise i.e. a cruise propeller

• High speed.

The climb propeller is usually

chosen when the aircraft normally operates from a restricted airfield or in high

density altitude conditions. The climb propeller will produce maximum efficiency

at full throttle around the best rate of climb airspeed and will perform fairly

well at take-off, but during the initial take-off acceleration even the climb

propeller may restrict the engine rpm to less than 75% power. The cruise

propeller will achieve maximum efficiency at 75% power at airspeeds around the

design cruising speed but aircraft take-off and climb performance will not be

the optimum. The cruise propeller usually has a little more pitch than the

standard propeller fitted to the aircraft. A high speed propeller might be

fitted when the aircraft is intended to be operating at, or above, rated power

for short periods – in speed competition for example.

A constant speed propeller allows the engine to

develop maximum rated power and rpm during the ground roll and to develop full

power throughout its normal rpm range. With a constant speed propeller the pilot

controls inlet manifold air pressure [MAP] with the throttle lever and

the engine rpm with the rpm control lever or knob/switches. The pilot has

several combinations of rpm/MAP to achieve a particular power setting. For

example, in one particular aircraft, the recommended combinations for 65% power

at sea level are 2100 rpm + 26 inches Hg MAP or 2200 + 25 inches or 2300 + 24

inches or 2400 + 23 inches. So you can use low rpm and high MAP or high rpm and

low MAP to achieve exactly the same power output. The low rpm / high MAP

combination probably gives more efficient cylinder charging and better

combustion plus less friction. The high MAP also acts as a cushion in the

cylinders, reducing engine stress. MAP is usually measured in inches of mercury

[Hg] rather than hectopascals. Standard sea level barometric pressure is 29.92

inches Hg or 1013.2 hPa.

The

windmilling propeller

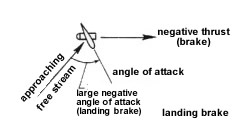

The angle of attack of a fixed

pitch propeller, and thus its thrust, depends on the forward speed of the

aircraft and the rotational velocity. Following a non catastrophic engine

failure the pilot tends to lower the nose so that forward airspeed is maintained

while at the same time the rotational velocity of the engine/propeller is

winding down. As the forward velocity remains more or less unchanged while the

rotational velocity is decreasing the angle of attack must be continually

decreasing and at some particular rpm the angle of attack will become negative

to the point where the lift component becomes negative ([reverses) and the

propeller autorotates, driving the engine. This acts as greatly increased

aerodynamic drag which seriously affects the aircraft's L/D ratio and thus glide

angles. The drag (including the negative lift) is much greater than that of a

stationary propeller, also the engine rotation may cause additional mechanical

problems if oil supply is affected.

If the forward speed is increased windmilling will increase, if forward speed is

decreased windmilling will decrease, thus the windmilling might be stopped by

temporarily reducing airspeed, probably to near stall, so that the negative lift

is decreased to the point where internal engine friction will stop rotation.

This is not something which should be attempted without ample height.

In the diagram the upper figure shows the forces associated with a section of a

propeller blade operating normally. The lower figure shows the forces and the

negative angle of attack (aoa) associated with the propeller now windmilling at

the same forward velocity.

A variable pitch propeller may have a feathering facility which turns the

blades to the minimum drag position (i.e. the blades are more or less aligned

fore and aft) and halts windmilling when the engine is stopped.

The runaway

propeller

As a propeller system increases

in complexity then the possibilities for malfunction increase. A problem

associated with constant speed propellers is governor failure during flight

which, in most installations, will cause the propeller blades to default to a

fine pitch limit. This greatly reduces the load on the power plant, and the

engine will immediately overspeed, particularly if in a shallow dive. The rpm of

an overspeeding engine – sometimes referred to as a 'runaway prop' – will

quickly go way past red-line rpm and, unless immediate corrective action is

taken, the engine is likely to self destruct and/or the propeller blades depart

the hub due to the increased centrifugal force.

The corrective action is to immediately close the throttle and reduce to minimum

flight speed by pulling the nose up. . Once everything is settled down fly

slowly, consistent with the fine pitch setting, to a suitable airfield using

minimum throttle movements. (The constant speed propeller fitted to a

competition aerobatic aircraft usually defaults to the coarse pitch limit to

prevent overspeeding but an immediate landing is required.)