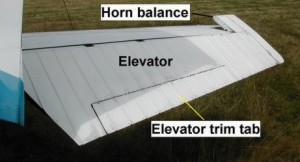

A trim tab is a small, adjustable hinged surface

on the trailing edge of the aileron, rudder, or

elevator control surfaces. Trim tabs are labour

saving devices that enable the pilot to release

manual pressure on the primary controls.

Some airplanes have trim tabs on all three

control surfaces that are adjustable from the

cockpit; others have them only on the elevator

and rudder; and some have them only on the

elevator. Some trim tabs are the

ground-adjustable type only.

The tab is moved in the direction opposite that

of the primary control surface, to relieve

pressure on the control wheel or rudder control.

For example, consider the situation in which we

wish to adjust the elevator trim for level

flight. ("Level flight" is the attitude of the

airplane that will maintain a constant

altitude.) Assume that back pressure is required

on the control wheel to maintain level flight

and that we wish to adjust the elevator trim tab

to relieve this pressure. Since we are holding

back pressure, the elevator will be in the "up"

position. The trim tab must then be adjusted

downward so that the airflow striking the tab

will hold the elevators in the desired position.

Conversely, if forward pressure is being held,

the elevators will be in the down position, so

the tab must be moved upward to relieve this

pressure. In this example, we are talking about

the tab itself and not the cockpit control.

Rudder and aileron trim tabs operate on the same

principle as the elevator trim tab to relieve

pressure on the rudder pedals and sideward

pressure on the control wheel, respectively.

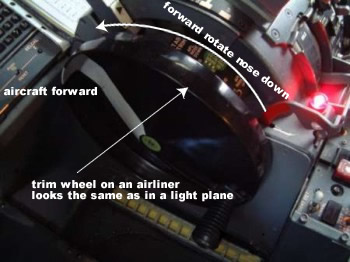

The tabs are usually controlled by a wheel which

is often situated on the floor between the two

front seats. Some aircraft have the trim

controlled by a small rocker switch on the

control column. The aircraft should be trimmed

after every change in attitude or power setting.

It takes a little practice to trim an aircraft,

but in the end it is done unconsciously.

Trim history

The trim tab or servo trim was invented by Anton Flettner, a German

aeronautical engineer. He started work in 1905 for the Zeppelin Company.

Died in 1962.

Trim

Most aircraft have single axis trim for the elevator. Airliners have

three-axis trim for the elevator, rudder and ailerons. Trim is used to

correct for any forces that might tend to counter your selected flight

performance. Trim allows the pilot to relax. A pilot who cannot trim will

be an exhausted pilot in a short time. It takes only a couple of flights

for a pilot to realize the benefits of trim. The best check for proper

trim setting for any flight configuration is to let go of the yoke

completely and see what the nose does.

The simplest elevator trim

uses a wheel, lever, or crank to pull a cable or rod attached to a trim

surface bell-crank. Other systems use a jackscrew and rod to set trim.

Electric trim is best used for coarse settings. Only the coordination of

eye and hand can correctly set fine trim settings. Using the trim control

positions the trim and the aircraft for the desired attitude.

If an aircraft is

improperly rigged trim is not the fix required. An aircraft that

consistently flies one wing low need help only a mechanic can give. The

aircraft wings have adjustments that can correct problems detected in

using trim.

The controllable trim tabs

are required on all aircraft. It is usually on only one side of the

elevators since they are both on the same rod (Cessna). It is hinged and

can be moved only by use of a cable system connected to the trim control

in the cockpit. The direction the tab moves causes an opposite deflection

of the control surface. The ground adjustable trim tab is a small surface

on the trailing edge of a control surface, most often the rudder, that can

be bent to set control forces at cruise speeds. The trim setting creates

the aerodynamic forces required to keep the elevator and the airspeed in

the desired position.

The three factors

affecting trim are the centre of gravity, airspeed and configuration

(flaps/gear). The passenger load will affect the centre of gravity and

require unique takeoff and level flight trim settings. Each trim setting

has a corresponding speed that the aircraft will seek and hold.

If you are holding any

pressure on the yoke against the trim setting a moment of distraction will

result in an airspeed change. A stabilized approach to landing is

difficult, to impossible, if the aircraft is not well trimmed. The less

skilled the pilot the more likely he is to neglect proper trim technique

and attempt to maintain control by arm and hand pressures. Good technique

requires that the pressures felt on the yoke be from pilot applied input.

Any pressures applied otherwise are indicative of improper trim. Trim is

the cruise control of flying. Not using trim is equivalent to being able

to turn on/off power steering.

Trim makes it possible for

the pilot to configure the aircraft to counteract and neutralize the

normal nose heavy condition. There is a designed twisting along the

longitudinal axis caused by a difference between the weight on the centre

of gravity and the lift acting through the centre of pressure. If the

pilot does not trim then control pressure must be held maintain the

negative lift value of the horizontal stabilizer and elevator. Trim allows

this control pressure to be adjusted for hands-off flight. In a trimmed

condition the pilot can feel the control pressures required to a acquire a

desired flight attitude. An improperly trimmed aircraft is constantly

seeking to relieve any pilot induced control pressure.

The original design of the

aircraft sets the shape, position, and size of flying surfaces and

controls so that in cruise conditions these would provide least resistance

and maximum speed. Outside of this condition a trim control was installed

to maintain the aircraft stability required for climb, descent, landings

and other flight speeds and configurations. On some aircraft the angle of

incidence of the horizontal stabilizer can be changed by a trim control.

This is more effective and efficient than a trim tab (Mooney). The

stabilator is another way (Piper). It is an airfoil that in one piece acts

as both stabilizer and elevator. The trim control of the stabilator acts

as both a trim and anti-servo tab (power assist). The yoke applies control

forces to the tab to move the entire control. No change in trim technique

is required in either case.

Ideally an aircraft would

have a three-axis trim; elevator, rudder, and aileron. Without such trim

some aircraft just fly crooked. Fixed tabs on the rudder and adjustment

screws on the wings can make semi-permanent or even permanent fixes to the

aircraft trimmed condition in level cruise. A pilot can, with low-wing

aircraft utilize fuel weight/consumption to adjust the aircraft 'trim'.

Passenger seating can also make a difference.

The aircraft trim system

is used to adjust the aerodynamic centre of lift as required to balance

the ever-changing centre of gravity primarily along the longitudinal axis

of the airplane. This relieves the pilot from having to maintain control

pressures on the yoke. The pitch can be varied with the trim wheel to

adjust for weight, configuration, speed and power. A pilot should be aware

that any change in these factors will require a trim change.

The trim system usually

consists of a cable from a moveable small surface on the empennage forward

to the cockpit. The FARs require that a trim position indicator exist in

the cockpit with a takeoff position especially marked and visible to the

pilot. Mooney aircraft move the entire empennage. Some of the surfaces

called trim tabs are fixed and can only be adjusted on the ground by

bending. The trim system is not intended as a primary flight control.

Remember, Trim effects will be reversed if the primary control is jammed.

Trim

Use

Correct use of the trim requires that control pressures be applied to

hold the desired flight attitude. Then the trim is adjusted to relieve

present control pressures. Some initial change in trim should always be

made since it reduces drag. If the aircraft is in an accelerating or

decelerating mode anticipatory trim changes may be desired. Proper trim is

a necessary part of flying from both operational and safety standpoints.

The skill of the pilot is proportional to ability to trim.

Being able to trim the

aircraft for any attitude requires that the pilot adjust the amount of

download on the horizontal tail surfaces. It is this download that

overcomes the nose weight of an aircraft. Download is 'lift' of the tail

surfaces directed opposite to the lift of the wing.

The important thing in

using trim is always to be able to keep track of where it is. This is the

reason I urge you to use a finger tip rather than a pinch. The fuel/pilots

location in the c-150/152 are so near the CG that the trim movement will

be rather constant. Any variation will be corrected if everything is

predicated on beginning at a constant. The constant that I use has always

been: Level cruise at 2400 rpm and hands off.

This constant works just a

well if using C-172 or C-182. The presence of a rear-seat passenger will

be corrected for using this constant. Pipers trim differently. Flaps

change pitch attitude significantly but require very little trim

adjustment. As you know the indicator markings are often illegible or not

calibrated. A slipping trim cable is a frequent problem.

Cruise-Control

Learning to trim for level flight requires that you think in terms of

setting as many constants as possible for a given flight situation. First,

get a constant level attitude. Using the nose/horizon reference is more

difficult than using the wing. The wing level with the horizon works best

with the high-wing types. Second, get a constant speed at cruise speed or

lower. If you exceed cruise speed without reducing power your trim setting

will set for the higher speed. You should practice reducing power to 75%

power setting as cruise. 2450 rpm is a good set. Third, trim off the

pressure.

Is their only one way to

trim? No. With experience you may just give a few flips and make a fine

adjustment as required. You can even make numerous small changes. Doing it

differently does not make it wrong. There is no one way to do anything in

flying. Different aircraft and different trim systems require different

techniques. The aim of my following suggestions is that it gets the

beginner into anticipating trim movements as may be required for every

change of configuration. Trim then becomes another constant.

Trimming off pressure is a

search for the trim position that allows the aircraft to be flown with

only one finger and the thumb. Which ever one you are using to hold

altitude tells you which way to move the trim. Most students tend to move

the trim more than required. You might do well as a student to use half as

much movement as you think is required. You are trimmed when both finger

and thumb need only to lightly brush the yoke. Getting trimmed to this

point makes flying enjoyable and relaxing. Unlike an automobile, a

correctly trimmed airplane can be flown hands-off. Once this sense of

'feel' is acquired you will not want to fly any other way. Every pilot has

a slightly different 'feel' of an aircraft so changing pilots usually

involves changing trim.

Every student and pilot

should use trim to create opportunities to fly with rudder. Training

aircraft usually have a rudder tab that has been set by prior pilots so

that very little rudder is required in straight-and-level cruise. You can

make slight turns using just the rudder with little difficulty. Steeper

turns with the rudder will cause a loss of altitude. Much of this altitude

is regained when using hard rudder to level the wings.

Once an aircraft is

trimmed for a particular airspeed in level flight, additional power or a

reduction in power will cause the aircraft to climb and descend at that

airspeed. You must exercise some yoke control and rudder to correct for

any transitional oscillations. Trim remains the same. Trim is the cruise

control of flying an aircraft. I very much recommend not changing trim

when descending from cruise to pattern altitude. Descend by reducing

power. Enter downwind at cruise speed until abeam the numbers. The

deceleration in airspeed while holding altitude on downwind will allow you

to trim for the approach speed while reaching the appropriate 'key'

position for turning base.

Airplanes should be

trimmed for every condition of flight except during times you may be

turning or changing airspeeds. Flying an aircraft out of trim makes

control difficult and wearisome. Initial trim settings should be just

'close'. Fine trim when the power and airspeed has stabilized. The check

of trim setting is confirmed by letting go of the controls.

Every control system has

inherent frictions that tend to keep them in position. In some cases this

internal aircraft factor may make an aircraft seem out of trim.

Occasionally an aircraft may be affected by atmospheric conditions. In

turbulence a tight grip will only accentuate the bumps. Single finger

control is best in choppy conditions.

If your aircraft has

rudder trim, you adjust it only after elevator trim has been fine-tuned.

Rudder is trimmed in wings-level flight with a nose-on reference point.

Use rudder pressure to maintain the reference point and then trim off the

pressure. Confirm rudder trim setting by letting go of all the controls.

Aileron trim, if there, is set much the same way.

Once an aircraft is completely trimmed it can be neatly controlled with

small brief rudder input. Pitch changes can be controlled with VERY small

power changes. Flying with just the rudder is a very useful experience.

Even in instrument conditions the rudder can be used. Step on the high

wing of the attitude indicator and the turn coordinator. Step on the

heading desired of the heading indicator. Such flying removes flying as a

problem part of the IFR equation.

Tight Grip vs light touch

The left hand has only two

useable digits while flying. The forefinger is behind the yoke for back

pressure and the thumb is for forward pressure. You cannot feel the

pressures requiring trim if a heavier touch is used. Tension is the

greatest single cause of a full tight grip. Note how a beginning driver

grips the wheel. The sooner the student learns that a light touch with

proper trim gives more positive control, the better. There is a safety

factor in this. Any distraction or movement of the body will affect yoke

pressure. This is especially true if the pressure is being held tightly

against the trim. The pilot with a light touch can let go of the yoke and

the plane will fly as trimmed. The tight grip increases fatigue as a

factor. Easy to say; difficult to do. IFR pilots do it better with a light

touch. A full grip on the yoke seems to result in inadvertent climbs and

turns. Tension is the greatest single cause of the tight full grip on the

yoke. The best analogy is the differences between student and experienced

drivers in holding the steering wheel of a car.

One Finger and a Thumb Flying

Over controlling is a symptom.

A student or pilot who is heavy, reactionary, or hesitant on the controls

is not yet a believer. The proficient pilot has faith in the airplane’s

ability to perform in a particular manner. All proficient flying is an act

of faith just as is having the runway disappear during a landing.

Turbulence is one of the

best opportunities for the pilot to see this. The natural, normal reaction

of a student pilot in turbulence is to grip the yoke more firmly. This is

what you do going over chuckholes in an automobile. In an airplane a firm

grip gives you a two-for-one bump. A light touch will reduce the extent of

light to moderate turbulence significantly.

With practice you can do it with your eyes closed. You will need to

SEE only

to confirm. Then just for fun you can move your arms forward and back to

initiate shallow climbs and descents.

Emergency Trim Use

If the elevator is locked as with a control lock, the use of trim

will be backwards. Any use of the trim will be as an elevator. To raise

the nose of the aircraft you must raise the trim tab. Confusing but true.

You and Your Autopilot

Is

the autopilot only an emergency device?

Is

the autopilot only an emergency device?

Is it an aid for the incompetent?

Is it an aid for the incompetent?

Is it a copilot to assist the pilot in need?

Is it a copilot to assist the pilot in need?

The autopilot has built-in complexity that is a potential hazard if not

understood.

The autopilot has built-in complexity that is a potential hazard if not

understood.

The autopilot is not a substitute for instrument competency.

The autopilot is not a substitute for instrument competency.

Poor instrument skills and reliance on the autopilot can kill.

Poor instrument skills and reliance on the autopilot can kill.

Some autopilots must be turned off rather than overridden.

Some autopilots must be turned off rather than overridden.

Autopilots should be turned off in turbulence

Autopilots should be turned off in turbulence

Do not takeoff or land with the autopilot.

Do not takeoff or land with the autopilot.

The autopilot probably has a minimum operating speed.

The autopilot probably has a minimum operating speed.

Altitude hold is not 'altitude return'.

Altitude hold is not 'altitude return'.

It is up to the pilot to become an expert systems manager.

It is up to the pilot to become an expert systems manager.

A pilot must be able to disconnect the autopilot without hesitation.

A pilot must be able to disconnect the autopilot without hesitation.

The autopilot can fly the approach while the pilot watches for the

airport.

The autopilot can fly the approach while the pilot watches for the

airport.

Autopilots do not have the capability to make a go-around or a missed

departure procedure.

Autopilots do not have the capability to make a go-around or a missed

departure procedure.

The autopilot allows a rested pilot to be there at the end of a long

flight.

The autopilot allows a rested pilot to be there at the end of a long

flight.

Cockpit housekeeping and planning is easier when on autopilot.

Cockpit housekeeping and planning is easier when on autopilot.

For every coupled approach you should make a hand-flown approach for

skill maintenance.

For every coupled approach you should make a hand-flown approach for

skill maintenance.

Now back to Trim:

In the 150 we initially put in three turns of trim down. In the

process of landing we took off three turns so the aircraft is trimmed for

level. Therefore, before we takeoff again we want to put in one full turn

down for takeoff and climb. This turn will give you very close to Vy

climb. Hands-off check of trim but using right rudder.

On reaching altitude,

lower the nose; hold altitude with pressure while taking off a full turn

of trim for level cruise. Leave the power in until reaching over 80-knots,

holding altitude to allow acceleration and then reduce the power to 2450

rpm. We are now back to our initial approach point. Hands-off.

Pinching Won't Work

Those who habitually

pinch the trim wheel will always be applying too little trim to make this

work.

Those who habitually

pinch the trim wheel will always be applying too little trim to make this

work.

You must learn to read

the nose and anticipate its rise and fall as to how much pressure is

required to stop at a

You must learn to read

the nose and anticipate its rise and fall as to how much pressure is

required to stop at a

given airspeed.

Then, based upon the pressure you need to hold a given airspeed, make an

adjustment of one or two buttons

Then, based upon the pressure you need to hold a given airspeed, make an

adjustment of one or two buttons

using the fingertip.

Once you get close adjust accordingly.

Once you get close adjust accordingly.

Trim Factors

Stability of an aircraft may be

judged by how well it holds a trimmed situation.

Stability of an aircraft may be

judged by how well it holds a trimmed situation.

Static stability exists when an aircraft is trimmed for a condition and

then moved will return as trimmed.

Static stability exists when an aircraft is trimmed for a condition and

then moved will return as trimmed.

A statically stable aircraft is easier to fly.

A statically stable aircraft is easier to fly.

A statically unstable aircraft is harder to fly.

A statically unstable aircraft is harder to fly.

A statically stable aircraft exists when the CG is forward of the wing

lift.

A statically stable aircraft exists when the CG is forward of the wing

lift.

the closer the centre of wing wing lift gets to the centre of gravity

the more unstable the aircraft

the closer the centre of wing wing lift gets to the centre of gravity

the more unstable the aircraft

FARs require aircraft to be statically stable with respect to speed

changes

FARs require aircraft to be statically stable with respect to speed

changes

Lift is commonly close to 25% aft of wings chord from the leading

edge.

Lift is commonly close to 25% aft of wings chord from the leading

edge.

Trim is used to adjust the tail to counter wings lift forward of the

centre of gravity by giving down-load.

Trim is used to adjust the tail to counter wings lift forward of the

centre of gravity by giving down-load.

The forward C.G requires a tail download as any reduction in speed will

lower the nose as a recovery

The forward C.G requires a tail download as any reduction in speed will

lower the nose as a recovery

About one pound of pressure on the yoke is required for every six knots

to prevent a change in airspeed

About one pound of pressure on the yoke is required for every six knots

to prevent a change in airspeed

Friction of control and connections is a constant difference related to

aircraft speed.

Friction of control and connections is a constant difference related to

aircraft speed.

You must overcome this designed-in friction before the controls move

You must overcome this designed-in friction before the controls move

FRSR is a term meaning

free return speed range

FRSR is a term meaning

free return speed range

The FRSR is the range of speeds that can be stabilized with a single

trim setting.

The FRSR is the range of speeds that can be stabilized with a single

trim setting.

Aft CG conditions lower the FRSR speed ranges.

Aft CG conditions lower the FRSR speed ranges.