introduction

Navigation is the art and science of getting from

point "A" to point "B" in the least possible time without losing your way. In

the early days of aviation, navigation was mostly an art. The simplest

instruments of flight had not been invented, so pilots flew "by the seat of

their pants". Today, navigation is a science with sophisticated equipment being

standard on most aircraft.

The type of navigation used by pilots

depends on many factors. The navigation method used depends on where the pilot

is going, how long the flight will take, when the flight is to take off, the

type of aircraft being flown, the on-board navigation equipment, the ratings and

currency of the pilot and especially the expected weather.

To

navigate a pilot needs to know the following:

-

Starting point (point of departure)

-

Ending point (final destination)

-

Direction of travel

-

Distance to travel

-

Aircraft speed

-

Aircraft fuel capacity

-

Aircraft weight & balance information

With this information flight planning can commence and the proper method of

navigation can be put to use.

Basic Navigation

Pilotage

For

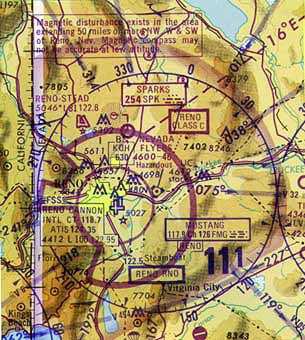

a non-instrument rated, private pilot planning to fly VFR (Visual Flight Rules)

in a small, single engine airplane around the local area on a clear day, the

navigation is simple. The navigation process for such a local trip would be

pilotage. (Bear in mind, however that the flight planning and preflight for such

a trip should be as thorough as if the pilot is preparing to fly

cross-country.)

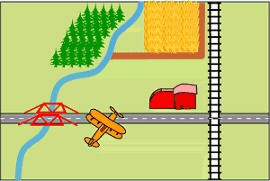

The pilotage method of navigation developed naturally through time as

aircraft evolved with the ability to travel increasingly longer distances.

Flying at low altitudes, pilots used rivers, railroad tracks and other visual

references to guide them from place to place. This method called pilotage is

still in use today. Pilotage is mainly used by pilots of small, low speed

aircraft who compare symbols on aeronautical charts with surface features on the

ground in order to navigate. This method has some obvious disadvantages. Poor

visibility caused by inclement weather can prevent a pilot from seeing the

needed landmarks and cause the pilot to become disoriented and navigate off

course. A lack of landmarks when flying over the more remote areas can also

cause a pilot to get lost.

Using pilotage for navigation can be as easy

as following an interstate highway. It would be difficult to get lost flying VFR

from Oklahoma City to Albuquerque on a clear day because all a pilot need do is

follow Interstate 40 west. Flying from Washington, DC to Florida years ago was

accomplished by flying the "great iron compass" also called the railroad

tracks.

Dead Reckoning

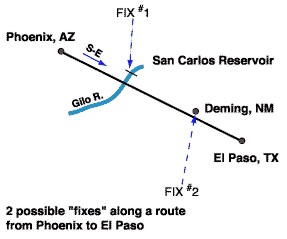

"Dead" Reckoning (or "Ded" for

Deductive Reckoning) is another basic navigational method used by low speed,

small airplane pilots. It is based on mathematical calculations to plot a course

using the elements of a course line, airspeed, course, heading and elapsed time.

During this process pilots make use of a flight computer. Manual or electronic

flight computers are used to calculate time-speed-distance measurements, fuel

consumption, density altitude and many other en route data necessary for

navigation.

The estimated time en route (ETE) can be calculated using the flight

distance, the airspeed and direction to be flown. If the route is flown at the

airspeed planned, when the planned flight time is up, the destination should be

visible from the cockpit. Navigating using known measured and recorded times,

distances, directions and speeds makes it possible for positions or "fixes" to

be calculated or solved graphically. A "fix" is a position in the sky reached by

an aircraft following a specific route. Pilots flying the exact same route

regularly can compute the flight time needed to fly from one fix to the next. If

the pilot reaches that fix at the calculated time, then the pilot knows the

aircraft is on course. The positions or "fixes" are based on the latest known or

calculated positions. Direction is measured by a compass or gyro-compass. Time

is measured on-board by the best means possible. And speed is either calculated

or measured using on-board equipment.

Navigating now by dead reckoning

would be used only as a last resort, or to check whether another means of

navigation is functioning properly. There are navigation problems associated

with dead reckoning. For example, errors build upon errors. So if wind velocity

and direction are unknown or incorrectly known, then the aircraft will slowly be

blown off course. This means that the next fix is only as good as the last

fix.

|