|

single pilot IFR

reprinted from AOPA

Is it safe to fly IFR as a single

pilot? This question is constantly debated by pilots. Most would agree that

flying IFR with an experienced and competent co-pilot enhances the safety of the

flight. However, single-pilot IFR flights are executed safely and without

incident hundreds of times every day. As a pilot, what you really want to know

is, how safe is it and can you do it safely? You must first ask yourself how

safe you want it to be. How much effort and money are you willing to invest?

Single-pilot IFR can be as safe as you choose to make it, and there are many

things you can do to make it safer. The purpose of this safety advisor is to

explore some of the things you might do to give yourself the safety advantage.

Although these suggestions are not all-inclusive, they should stimulate some

serious thought and introduce some new concepts. Those things over which you

have control must be controlled, and exposure to those that you don’t must be

minimized.

Introduction

The AOPA Air Safety Foundation’s aviation safety database, which contains more

than 40,000 general aviation accident reports, reveals that single-pilot IFR

flights generate several times as many accidents as those flown with a pilot and

copilot. We know intuitively, but without statistical proof, that most general

aviation IFR operations are flown by a single pilot. Although exposure alone may

explain a large part of the difference in the number of accidents, it’s clear

that single-pilot IFR is an area warranting special attention. When reviewed in

combination with FAA flying-hour activity reports, the database further reveals

that the accident rate at night under IMC conditions is 75% higher than that for

daytime IMC flying. Most IMC accidents occur during cruise (VFR into IMC) or

approach (descent below approach minimums). Not many surprises here, are there?

We would have suspected as much. Yes, there are challenges with single-pilot IFR.

Virtually no type of flying requires greater skill and concentration, imposes

greater work loads and mental stress, and extracts higher penalties for mistakes

than single-pilot IFR. Near-perfect performance is the minimum standard. That

standard can be attained and maintained, but it takes a dedicated commitment on

the part of the pilot to get the most utility from his flying at the highest

level of safety possible.

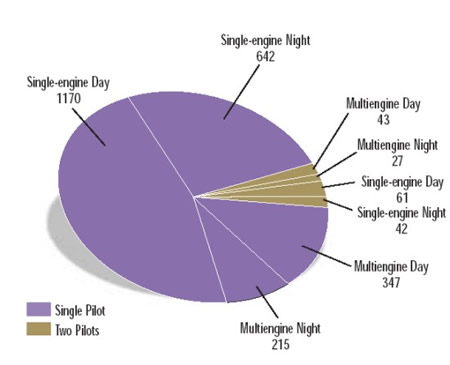

Distribution of Instrument

Accidents by Type of Aircraft and Number of Pilots (1983-1999)

More than two and one-quarter times as many IFR hours are

flown during daylight than are flown during darkness. More accidents occur in

daylight than darkness; accident rates, however, are based on the number of

accidents per 100,000 hours flown.

What’s the Problem?

A single pilot flying hard IFR is pilot, navigator, radio operator, systems

manager, records keeper, oft-times flight attendant, and sometimes zoo keeper.

It sure helps to have a copilot to share the duties and back up your actions,

but when you don’t have a copilot—and most general aviation single-engine and

light twin pilots don’t—you must cope and cope well. The obvious problem is high

work load, and in high-density traffic areas under very poor weather conditions,

the work load can become extremely high—even to the point of exceeding your

capabilities. Capabilities vary from pilot to pilot and, with a given pilot,

vary with time and circumstances. Let’s investigate those factors that affect

your capability, determine what you have the power to control, and then decide

what you can do to assure that you are operating at peak performance at all

times. You know that you are going to face a heavy work load. You must be

prepared to deal with it so that problems don’t compound to an overwhelming

point. The work load and stress go up dramatically when the unexpected happens.

Any surprise or distraction puts you in the reactive mode and starts to wrest

control from you. The ability to react and regain control is a measure of a good

instrument pilot. A second or third distraction encountered while still

wrestling with the first can rapidly escalate to an out-of-control situation.

The distractions can be as simple as arriving at a fix without having planned

your subsequent actions or as complex as having an engine fail at localizer

interception. Most people can juggle two balls, but three or more?

Prepare—Don’t Gamble

The obvious solution is to plan ahead in excruciating detail everything that can

be anticipated. Let’s take the airplane and equipment first. Are you planning to

have a vacuum pump fail on this flight? Of course not. But you can make certain

that the airplane was inspected as required, that you preflighted the system as

recommended, that you know how the system works, what the indications of a

failure are, and what procedures are recommended in the emergency checklist. If

you don’t yet have an intimacy with this particular type of airplane or can’t

determine that everything is as it should be before takeoff, then don’t risk an

IFR flight. Don’t gamble. Gambling is based on chance, and chance by definition

means that some percentage of the time the results will favour you, and

sometimes they will not.

Equipment—How Much Is Enough?

Part of planning ahead is making sure your aircraft is properly equipped to make

IFR flight easier. If you own your airplane, this is under control within some

financial limits. Those of you who rent are limited to looking for an FBO that

puts a little extra into its IFR airplanes and your complementing it with

certain portable equipment such as headsets, boom microphones, push-to-talk

switches, stopwatches, intercoms, etc. Today, we generally consider minimum IFR

equipment to be dual nav/coms, glideslope and marker beacon receivers, and an

ADF, although IFR flight can be done legally with less. Let’s look at a few

additions that can be very helpful. A headset with boom microphone and a

yoke-mounted pushto- talk switch are high on most pilots’ lists. The ability to

reply without reaching for the hand mike eliminates a major distraction that

always comes just when you need both hands for something else. The headset that

the boom mic attaches to also solves most of the confusion of missed or

misunderstood transmissions by providing clearer audio reception and shielding

external noise. An autopilot slaved to a heading bug is invaluable in keeping

the airplane right side up and going in the general direction desired while

reading charts, copying revised clearances, tuning radios, etc.

Altitude-hold and coupling features are added

benefits, but even a wing leveller is much better than nothing and can serve

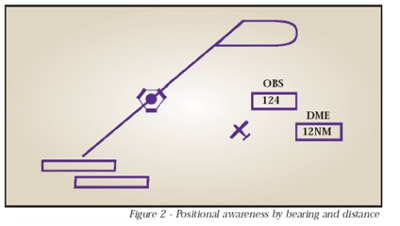

quite well. The minimum aid in keeping you precisely aware of your position at

all times is a DME. A radial and distance and a little thought are all you need

to avoid ever being surprised when it’s time to take the next action. Of course,

an RNAV, GPS, or loran is great and can give you distance information, plus a

lot more. A word of caution is appropriate here. Unless you learn to use these

receivers efficiently and understand their limitations, the potential for errors

exists. Some devices are so difficult to program that they wind up increasing

the work load and becoming major distractions in themselves. The next favourite

item is the ability to preselect frequencies on the com and nav receivers and

call them up with the press of a button. This enables you to plan ahead and

avoid distractions. A much preferred radio is one that displays both the active

and preselected frequencies simultaneously. With this feature, you can be

prepared for the next two or three frequency changes and also return

instantaneously to the last one when no contact is made after a change—all this

without the need to grab pencil and paper. If your wish list were unlimited

(which it isn’t), it would probably include electric trim, an HSI, an RMI, a

remote ID button, an altitude preselect and alerter on the autopilot, a radar

altimeter, and a host of others.

Most pilots are nuts about gadgets, and all of

these things can contribute to easing the work load while providing more

information and avoiding distractions. However, the few mentioned first will do

quite nicely and probably provide the greatest dividends for the smallest

investment. Please don’t think that simply loading the airplane with every

conceivable device you can afford solves the problem. That is not advocated

here, nor will it automatically decrease the work load and enhance safety.

Pilots must thoroughly understand each aid used. Better to be competent in the

essential equipment than confused and intimidated by sophisticated but poorly

understood equipment. Don’t overlook a worthy and relatively inexpensive

addition to every IFR pilot's flight kit: a good handheld nav/com transceiver.

The true value of this item will not be fully appreciated until you suffer

complete electrical failure in IMC conditions. It is also quite useful for

obtaining clearances before engine start, saving fuel when experiencing ATC

ground delays, getting weather reports, and a number of other around-the-airport

uses.

Organization

Probably the easiest way for an otherwise competent pilot to make single-pilot

IFR simpler is through advance planning and organization. This means having a

cockpit so neat and tidy that your mother would be proud of you. Since there

isn’t room in the cockpit for everything, preselect every chart and publication

you need. Put them in the order you expect to use them and have them open,

folded, or tabbed as appropriate. Put them away when finished. Have pencil and

paper handy. Stick-on note paper is excellent and can also be used to cover

malfunctioning instruments. Keep flashlights, calculators, plotters, etc.,

available but out of the way when not needed. There are kneeboards, lapboards,

clipboards, chart bags, yoke clips, and many other aids to help you

organize—find what serves you best. Some pilots like to have formatted forms

prepared on which to copy weather and clearances. An approach chart holder

centred on the yoke can be invaluable.

Real-Time Weather

What we have been talking about is normally referred to as “cockpit resource

management,” a buzz phrase that simply means: What tools are available when

flying, and how can you use them most efficiently? You should not overlook some

resources necessary to safely negotiate your way through the murk while avoiding

the really hazardous stuff. Real-time weather information comes from both

cockpit located gadgets and the services provided by ground-based systems. In

any case, it is the job of the pilot in command to manage the acquisition of

needed data and integrate it into the execution of the flight—another ball to

juggle. As you planned this flight, you gathered existing and forecast weather

from several sources, from TV to DUAT or the final briefing by the flight

service station specialist. How to best do this is a subject unto itself and is

discussed at length in another AOPA Air Safety Foundation safety advisor:

Weather Strategies.

As we all know, however, once en route the weather

will change, and it will probably not be as forecast. An axiom about a forecast

is that the weather will always be either better or worse than forecast but

never as forecast. As a flight progresses, it is a great comfort to find things

getting better than expected, and you want to enjoy that warm feeling as soon as

possible. On the other hand, if it is getting worse than expected, it behoves

you to know that as soon as possible to avoid those unwanted surprises and, if

necessary, execute a contingency plan in a timely manner. Your best source of

weather updates in flight is from the En route Flight Advisory Service (EFAS),

known as “Flight Watch,” available on 122.0 MHz. EFAS is designed for just what

you want, a continuous exchange between pilots in flight and Flight Watch

personnel. It provides the latest information on current weather reports and

hazardous weather as observed by other pilots or on weather radar.

Here’s where you find out about thunderstorms,

turbulence, icing, low visibilities, and high winds. Often you can get

weather-related assistance from the controlling agency. Ground controllers may

be willing to help you out, but are often unable because of their high work

load. Their primary responsibilities are controlling and separating IFR traffic.

Air traffic radar is not designed to see weather, and what capability it does

have may be suppressed in order to see aircraft. The time that help is most

needed is usually in circumstances when it is least likely to be available. If

you have storm avoidance equipment such as airborne radar or Stormscope, you are

indeed a leg up. ATC is most generous, whenever possible, in allowing route

deviation to avoid hazardous weather, when you can provide your own warning

source. However, possessing a radar or Stormscope is not synonymous with using

them to the best advantage. So take the time to get proper training in their

operation.

Avoid Distractions Through Planning

Distractions must be avoided. Passengers are one of the most obvious sources of

distraction. Brief them in advance that there will be times when your attention

will be completely devoted to flying the airplane. They will understand

—especially when they can no longer see the ends of the wings. If they still

won’t leave you alone to concentrate, try sweating profusely in an otherwise

cold cockpit. That will get their attention. Another distraction is self-induced

and comes from lack of anticipating and planning ahead. Advance planning begins

on the ground. Think through and mentally execute the entire flight, at least to

the extent that you look at each phase and say to yourself, “I expect to do thus

and so, and I will need such and such available.” Look at the SIDs, STARs, and

approaches you expect to fly, as well as those you might be given at both your

destination and your alternate.

Stay Ahead of the Airplane While in Flight—Act Rather Than React

In flight, there is a systematic thought process that is especially helpful. It

is similar to position reporting—something we don’t often do anymore. Report

where you are, give the ETA at the next reporting point, and the name of the

subsequent one. This analogy concerns events and actions. An “event” is a

happening such as station passage, arriving at an altitude, intercepting the

glideslope, and so on. When an event happens, “action” is required. Say (to

yourself) what the next expected event is, what action is required, and what

will be the subsequent event (see Figure 1). As an example, think of

intercepting the localizer on an ILS approach. “At intercept, I must turn to the

inbound heading and start a descent to 2,000 feet.

The next event will be arrival at 2,000 feet. All I

have to do in the meantime is track the localizer and descend. When I get to

2,000 feet, I must level off and start looking for glideslope interception.”

After each event happens and the required action has been taken, you mentally

redefine the next event and subsequent one. Some pilots do this aloud, and this

seems to help them. Either way, doing this helps prevent surprises and keeps you

ahead of the aircraft. There are many pilots who can fly precision instruments,

but have no systematic way of anticipating their next move to the extent that

they become ineffective as instrument pilots. Some pilots being vectored to

localizer interception concentrate so hard on the heading and altitude that they

fly right through the localizer. Ever happen to you? Try this thought process

consciously a few times, and see if your preparedness improves.

Know Where You Are—Always

Maintain “positional awareness.” This simply means knowing where you are at all

times. If you follow your position even when being vectored, you know what to

anticipate next and are never surprised. Here’s where DME comes in handy. If

what you hear does surprise you, maybe it’s time to question the controller.

They have been known to make mistakes. To maintain positional awareness,

sometimes it’s helpful to sketch your position on the lapboard or make dots on

the approach chart. A centred OBS needle with a “from” indication, coupled with

a closely approximated DME measurement (radial and distance), immediately

resolves all questions about where you are (see Figure 2). Equally as important

is “situational awareness.” Is the fuel remaining adequate or have routing

changes or extensive vectoring consumed more fuel than planned? Is the current

weather consistent with the forecast for both the destination and alternate or

is the trend better or worse than forecast? Can you expect a straight-in

approach, or will it be necessary to circle to land? You must stay aware of any

changes affecting the safety of flight to make decisions en route. The flight is

not over until the airplane is safely at rest on the ground.

Unofficial Copilot?

A question that always comes up when single-pilot IFR is discussed is, what

about using a nonpilot as a pseudo copilot? There are many things a second

person can do to relieve the work load. However, there are also some serious

cautions to be aware of when using the help of a nonpilot. First of all, know

who is helping and what they know or don’t know about flying. Know whether they

might be prone to show too much initiative in helping you out. The potential for

disaster is great when using the wrong person and, in the best case, can result

in increased, rather than decreased, work load. Having said all that, yes, a

spouse or companion who frequently flies with you and understands exactly what

you want done, and in whom you have confidence that unwanted actions will not

occur, can be a help. Train them, brief them thoroughly, and use their help with

discretion.

Currency and Training

Without question, the most essential and important piece of the single-pilot IFR

equation revolves around currency and recurrent training, the key to

proficiency. Do you recall the expression used earlier: “an otherwise competent

pilot”? All of the helpful hints, suggestions, and equipment in the world are

worthless if the pilot is not physically and mentally healthy, knowledgeable,

well trained, skilful, and current. Don’t fly unless you’re physically and

mentally fit. That’s common sense, and we won’t belabour that point. Skill is in

a separate category from the other attributes needed. Skill is a result of some

level of innate ability, intelligence, and motor reactions you possess that are

channelled and directed by training and perfected by practice.

Good training can allow you to make the most of

what you start with, but practice is what results in the highest level of

performance achievable. Remember when you first started flying, and it took 100

percent of your attention to fly straight and level? Only through practice does

flying become automatic, and the level of proficiency required to be a good

instrument pilot is that where basic control of the aircraft requires no

conscious thought. Routine manoeuvres must be instinctive and automatic or they

become distractions that interfere with procedures that do require attention and

conscious thought.

All flying, whether IFR or VFR, is a matter of continuously correcting

deviations from the desired flight parameters. How quickly you recognize a

deviation and how smoothly you correct it is a measure of your skill. The Old

Pro, for whom all instruments seem to freeze in the right position, simply

perceives deviations almost before they become apparent and corrects them

instinctively with such small and smooth control pressures that you don’t

realize a correction has taken place. You must reach a level where you interpret

and respond automatically to integrated instrument indications and not to

one-at-a-time interpretations. For instance, if your airplane is below the

desired altitude, do you correct with pitch, with power, or with both?

Obviously, it depends upon other things such as what the airspeed is doing and

what the attitude is. If you have to think about it rather than seeing the

situation as a whole and reacting instinctively, then you are not ready to face

the demands of serious instrument flying, especially alone.

Such skills come only through practice and can be

retained only through practice. Simulators, procedures trainers, or PC training

devices can help to retain and sharpen your basic flying skills. Even though it

may not duplicate your cockpit or your airplane’s flying characteristics, the

basics of instrument interpretation and aircraft control are universal. One hour

in a simple trainer prior to an instrument flight can significantly improve your

scan and technique and will show in your performance. Not only is practice

essential, but every pilot should periodically fly with an instructor to check

habits and review procedures. Choose only instructors who are actively teaching

instruments, for they will be most current themselves. Also, try to fly with

different instructors. You’d be surprised how many new tidbits you pick up, and

a fresh perspective is always helpful.

When you practice, don’t forget the emergencies. These are the ultimate

distractions. Plan for emergencies and practice emergencies. If you use a

simulator, practice to failure. In other words, compound the adversities to the

point you do overload. You can learn a lot about your limitations and also

expand your capabilities. When an emergency occurs, remember to take your time.

Be deliberate, control the aircraft, handle the emergency, navigate, and then

communicate.

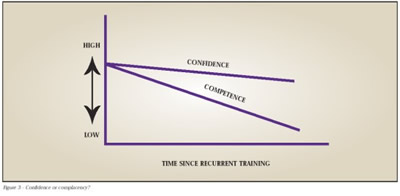

Confidence or Complacency?

The better you get, the more confident you become.

When confidence becomes complacency, you’re in deep trouble. Without modesty,

when you really are good, you know it. Constantly be on guard that your

confidence doesn’t exceed your ability. Unfortunately, our skills deteriorate at

a different rate than does our confidence (see Figure 3). Without periodically

testing ourselves and re-establishing our skill level through currency practice,

we can wind up in exactly that state—confidence well beyond competence.

In Summary

Consider the following recommendations:

-

Practice to stay current (include

a simulator or procedures trainer if available).

-

Don’t let your confidence exceed

your ability.

-

Be aware of your mental and

physical condition.

-

Control fatigue.

-

Pay attention to detail when

checking equipment and weather.

-

Flight plan thoroughly. Walk

through your entire proposed flight, and rehearse alternative approaches,

alternates, missed approaches, and emergencies.

-

Prepare in advance: Organize

your charts and the cockpit.

-

Stay continuously aware of your

position in space, the weather, and fuel remaining.

Now ask the question again: Is single-pilot IFR safe? Safe instrument flying is

a matter of attitude and discipline. If you have the proper attitude and the

self-discipline to follow the recommendations made here, you can enjoy a long

and successful career of single-pilot IFR flying.

|