| Aurora Borealis -

Northern Lights

The aurora is a glow observed in the night

sky, usually in the polar zone. For this reason some scientists call it a

"polar aurora" (or "aurora polaris"). In northern latitudes, it is known

as "aurora borealis" which is Latin for "northern dawn" since in Europe

especially, it often appears as a reddish glow on the northern horizon as

if the sun were rising from an unusual direction. The aurora borealis is

also called the "northern lights". The aurora borealis most often occurs

from September to October and March to April. Its southern counterpart,

"Aurora Australis", has similar properties.

The aurora is now known to be caused by

electrons of typical energy of 1-15 keV, i.e. the energy obtained by the

electrons passing through a voltage difference of 1,000-15,000 volts. The

light is produced when they collide with atoms of the upper atmosphere,

typically at altitudes of 80-150 km. It tends to be dominated by emissions

of atomic oxygen--the greenish line at 557.7 nm and (especially with

electrons of lower energy and higher altitude) the dark-red line at 630.0

nm. Both these represent "forbidden" transitions of atomic oxygen from

energy levels which (in absence of collisions) persist for a long time,

accounting for the slow brightening and fading (0.5-1 sec) of auroral

rays. Many other lines can also be observed, especially those of molecular

nitrogen, and these vary much faster, revealing the true dynamic nature of

the aurora.

Auroras can also be observed in the ultra-violet (UV) light, a very good

way of observing it from space (but not from ground--the atmosphere

absorbs UV). The "Polar" spacecraft even observed it in X-rays. The image

is very rough, but precipitation of high-energy electrons can be

identified.

Typically the aurora appears either as a

diffuse glow or as "curtains" that approximately extend in the east-west

direction. At some times, they form "quiet arcs", at others ("active

aurora") they evolve and change constantly. Each curtain consists of many

parallel rays, each lined up with the local direction of the magnetic

field lines, suggesting that aurora is shaped by the Earth's magnetic

field, Indeed, satellites show auroral electrons to be guided by magnetic

field lines, spiralling around them while moving earthwards.

The curtains often show folds called "striations". When the field line

guiding a bright auroral patch leads to a point directly above the

observer, the aurora may appear as a "corona" of diverging rays, an effect

of perspective.

In 1741 Hiorter and Celsius first noticed other evidence for magnetic

control, namely, large magnetic fluctuations occurred whenever the aurora

was observed overhead. This indicates (it was later realized) that large

electric currents were associated with the aurora, flowing in the region

where auroral light originated. Kristian Birkeland (1903) deduced that the

currents flowed in the east-west directions along the auroral arc, and

such currents, flowing from the dayside towards (approximately) midnight

were later named "auroral electrojets"

a corona

Still more evidence for a magnetic connection

are the statistics of auroral observations. Elias Loomis (1860) and later

in more detail Hermann Fritz (1881) established that the aurora appeared

mainly in the "auroral zone", a ring-shaped region of approx. radius 2500

km around the magnetic pole of the Earth, not its geographic one. It was

hardly ever seen near that pole itself. The instantaneous distribution of

auroras ("auroral oval", Yasha Feldstein 1963) is slightly different,

centred about 3-5 degrees nightward of the magnetic pole, so that auroral

arcs reach furthest equator-ward around midnight.

Aurora Australis

the solar wind and magnetosphere

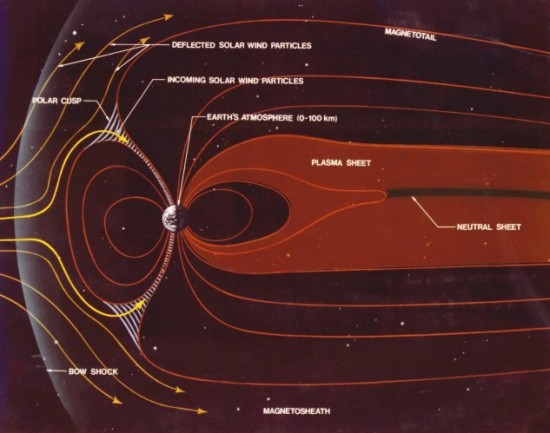

The Earth is constantly immersed in the solar

wind, a rarefied flow of hot plasma (gas of free electrons and positive

ions) emitted by the sun in all directions, a result of the million-degree

heat of the sun's outermost layer, the solar corona. The solar wind

usually reaches Earth with a velocity around 400 km/s, density around 5

ions/cc and magnetic field intensity around 2–5 nT (nanoteslas; the

Earth's surface field is typically 30,000–50,000 nT). These are typical

values. During magnetic storms, in particular, flows can be several times

faster; the interplanetary magnetic field (IMF) may also be much stronger.

The IMF originates on the sun, related to the field of sunspots, and its

field lines (lines of force) are dragged out by the solar wind. That alone

would tend to line them up in the sun-earth direction, but the rotation of

the Sun skews them (at Earth) by about 45 degrees, so that field lines

passing Earth may actually start near the western edge ("limb") of the

visible sun.

The Earth's magnetosphere is the space region dominated by its magnetic

field. It forms an obstacle in the path of the solar wind, causing it to

be diverted around it, at a distance of about 70,000 km (before it reaches

that boundary, typically 12,000–15,000 km upstream, a bow shock forms).

The width of the magnetospheric obstacle, abreast of Earth is typically

190,000 km, and on the night side a long "magnetotail" of stretched field

lines extends to great distances.

frequency of occurrence

The aurora is a common occurrence in the

ring-shaped zone. It is occasionally seen in temperate latitudes, when a

strong magnetic storm temporarily expands the auroral oval. Large magnetic

storms are most common during the peak of the 11-year sunspot cycle, or

during the 3 years after that peak. However, within the auroral zone the

likelihood of an aurora occurring depends mostly on the slant of IMF lines

(known as Bz, pronounced "bee-sub-zed"), being greater with southward

slants.

Geomagnetic storms that ignite auroras actually happen more often during

the months around the equinoxes. It is not well understood why geomagnetic

storms are tied to the Earth's seasons when polar activity is not. It is

known, however, that during spring and autumn, the earth's and the

interplanetary magnetic field link up. At the magnetopause, Earth's

magnetic field points north. When Bz becomes large and negative (i.e., the

IMF tilts south) it can partially cancel Earth's magnetic field at the

point of contact. South-pointing Bz's open a door through which energy

from the solar wind can reach Earth's inner magnetosphere.

The peaking of Bz during this time is a result of geometry. The

interplanetary magnetic field comes from the Sun and is carried outward

the solar wind. Because the Sun rotates the IMF has a spiral shape.

Earth's magnetic dipole axis is most closely aligned with the Parker

spiral in April and October. As a result, southward (and northward)

excursions of Bz are greatest then.

However, Bz is not the only influence on

geomagnetic activity. The Sun's rotation axis is tilted 7 degrees with

respect to the plane of Earth's orbit. Because the solar wind blows more

rapidly from the Sun's poles than from its equator, the average speed of

particles buffeting Earth's magnetosphere waxes and wanes every six

months. The solar wind speed is greatest -- by about 50 km/s, on average

-- around Sept. 5th and March 5th when Earth lies at its highest

heliographic latitude.

Still, neither Bz nor the solar wind can fully explain the seasonal

behaviour of geomagnetic storms. Those factors together contribute only

about one-third of the observed semi-annual variation.

the origin of the aurora

The ultimate energy source of the aurora is

undoubtedly the solar wind flowing past the Earth.

Both the magnetosphere and the solar wind consist of plasma, which can

conduct electricity. It is well known (since Faraday's work around 1830)

that if two electric conductors are immersed in a magnetic field and one

moves relative to the other, while a closed electric circuit exists which

threads both conductors, then an electric current will (usually) arise in

that circuit. Electric generators of dynamos make use of this process

("the dynamo effect"), but the conductors can also be plasmas or other

fluids.

In particular the solar wind and the magnetosphere are two electrically

conducting fluids with such relative motion, and should be able (in

principle) to generate electric currents by "dynamo action", in the

process also extracting energy from the flow of the solar wind. The

process is hampered by the fact plasmas conduct easily along magnetic

field lines but not so perpendicular to them. It is therefore important

that a temporary magnetic interconnection be established between the field

lines of the solar wind and those of the magnetosphere, by a process known

as magnetic reconnection. It happens most easily with a southward slant of

interplanetary field lines, because then field lines north of Earth

approximately match the direction of field lines near the north magnetic

pole (namely, into the earth), and similarly near the southern pole.

Indeed, active auroras (and related "substorms") are much more likely at

such times.

Electric currents originating in such fashion apparently give auroral

electrons their energy. The magnetospheric plasma has an abundance of

electrons: some are magnetically trapped, some reside in the magnetotail,

and some exists in the upwards extension of the ionosphere, which may

extend (with diminishing density) some 25,000 km around the Earth.

Bright auroras are generally associated with

Birkeland currents (Schield et al., 1969; Zmuda and Armstrong, 1973) which

flow down into the ionosphere on one side of the pole and out on the

other. In between, some of the current connects directly through the

ionospheric E layer (125 km), the rest ("region 2") detours, leaving again

through field lines closer to the equator and closing through the "partial

ring current" carried by magnetically trapped plasma. The ionosphere is an

ohmic conductor, so such currents require a driving voltage, which some

dynamo mechanism can supply. Electric field probes in orbit above the

polar cap suggest voltages of the order of 40,000 volts, rising up to more

than 200,000 volts during intense magnetic storms.

Ionospheric resistance has a complex nature, and leads to a secondary Hall

current flow. By a strange twist of physics, the magnetic disturbance on

the ground due to the main current almost cancels out, so most of the

observed effect of auroras is due to a secondary current, the auroral

electrojet. An auroral electrojet index (measured in nanotesla) is

regularly derived from ground data, and serves as a general measure of

auroral activity.

However, ohmic resistance is not the only obstacle to current flow in this

circuit. The convergence of magnetic field lines near Earth creates a

"mirror effect" which turns back most of the down-flowing electrons (where

currents flow upwards), inhibiting current-carrying capacity. To overcome

this, part of the available voltage appears along the field line

("parallel to the field"), helping electrons overcome that obstacle by

widening the bundle of trajectories reaching Earth; a similar "parallel

voltage" is used in "tandem mirror" plasma containment devices. A feature

of such voltage is that it is concentrated near Earth (potential

proportional to field intensity; Persson, 1963) and indeed, as deduced by

Evans (1974) and confirmed by satellites, most auroral acceleration occurs

below 10,000 km. Another indicator of parallel electric fields along field

lines are beams of upwards flowing O+ ions observed on auroral field

lines.

While this mechanism is probably the main source of the familiar auroral

arcs, formations conspicuous from the ground, more energy might go to

other, less prominent types of aurora, e.g. the diffuse aurora (below) and

the low-energy electrons precipitated in magnetic storms.

Some O+ ions ("conics") also seem accelerated in different ways by plasma

processes associated with the aurora. These ions are accelerated by plasma

waves, in directions mainly perpendicular to the field lines. They

therefore start at their own "mirror points" and can travel only upwards.

As they do so, the "mirror effect" transforms their directions of motion,

from perpendicular to the line to lying on a cone around it, which

gradually narrows down.)

In addition, the aurora and associated currents produce a strong radio

emission around 150 kHz known as auroral kilometric radiation (AKR,

discovered in 1972). Ionospheric absorption makes AKR observable from

space only.

These "parallel voltages" accelerate electrons to auroral energies and

seem to be a major source of aurora. Other mechanisms have also been

proposed, in particular, Alfvén waves, wave modes involving the magnetic

field first noted by Hannes Alfvén (1942), which have been observed in the

lab and in space. The question is however whether this might just be a

different way of looking at the above process, because this approach does

not point out a different energy source, and many plasma bulk phenomena

can also be described in terms of Alfvén waves.

Other processes are also involved in the aurora, and much remains to be

learned. Auroral electrons created by large geomagnetic storms often seem

to have energies below 1 keV, and are stopped higher up, near 200 km. Such

low energies excite mainly the red line of oxygen, so that often such

auroras are red. On the other hand, positive ions also reach the

ionosphere at such time, with energies of 20-30 keV, suggesting they might

be an "overflow" along magnetic field lines of the copious "ring current"

ions accelerated at such times, by processes different from the ones

described above.

|