|

the

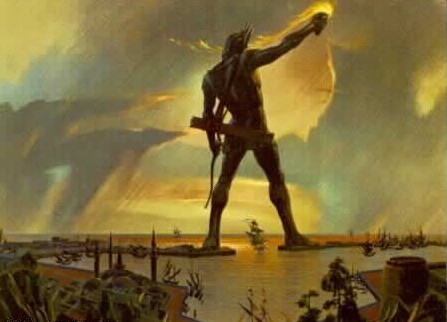

Colossus of Rhodes

The Colossus stood at the harbour entrance

Travellers to New York City harbour see a marvellous sight. Standing on a

small island in the harbour is an immense statue of a robed woman, holding

a book and lifting a torch to the sky. The statue measures almost

one-hundred and twenty feet from foot to crown. It is sometimes referred

to as the "Modern Colossus," but more often called the Statue of Liberty.

This awe-inspiring statue

was a gift from France to America and is easily recognized by people

around the world. What many visitors to this shrine to freedom don't know

is that the statue, the "Modern Colossus," is the echo of another statue,

the original colossus that stood over two thousand years ago at the

entrance to another busy harbour on the Island of Rhodes. Like the Statue

of Liberty, this colossus was also built as a celebration of freedom. This

amazing statue, standing the same height from toe to head as the modern

colossus, was one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

The island of Rhodes was

an important economic centre in the ancient world. It is located off the

South-western tip of Asia Minor where the Aegean Sea meets the

Mediterranean. The capitol city, also named Rhodes, was built in 408 B.C.

and was designed to take advantage of the island's best natural harbour on

the northern coast.

In 357 B.C. the island was

conquered by Mausolus of Halicarnassus (whose tomb is one of the other

Seven Wonders of the Ancient World), fell into Persian hands in 340 B.C.,

and was finally captured by Alexander the Great in 332 B.C.. When

Alexander died of a fever at an early age, his generals fought bitterly

among themselves for control of Alexander's vast kingdom. Three of them,

Ptolemy, Seleucus, and Antigous, succeeded in dividing the kingdom among

themselves.

The Rhodians supported

Ptolemy (who wound up ruling Egypt) in this struggle. This angered

Antigous who sent his son Demetrius to capture and punish the city of

Rhodes.

The war was long and

painful. Demetrius brought an army of 40,000 men. This was more than the

entire population of Rhodes. He also augmented his force by using Aegean

pirates.

The city was protected by

a strong, tall, wall and the attackers were forced to use siege towers to

try and climb over it. Siege towers were wooden structures often armed

with catapults that could be moved up to a defender's walls to allow the

attackers to scale them. While some were designed to be rolled up on land,

Demetrius used a giant tower mounted on top of six ships lashed together

to make his attack. This tower, though, was turned over and smashed when a

storm suddenly approached. The battle was won by the Rhodians.

Demetrius had a second

super-tower built. This one stood almost 150 feet high and some 75 feet

square at the base. It was equipped with many catapults and skinned with

wood and leather to protect the troops inside from archers. It even

carried water tanks that could be used to fight fires started by flaming

arrows. This tower was mounted on iron wheels and could be rolled up to

the walls.

When Demetrius attacked

the city, the defenders stopped the war machine by flooding a ditch

outside the walls and miring the heavy monster in the mud. By then almost

a year had gone by and a fleet of ships from Egypt arrived to assist the

city. Demetrius withdrew quickly leaving the great siege tower where it

was.

To celebrate their victory

and freedom, the Rhodians decided to build a giant statue of their patron

god Helios. They melted down bronze from the many war machines Demetrius

left behind for the exterior of the figure and the super siege tower

became the scaffolding for the project. According to Pliny, a historian

who lived several centuries after the Colossus was built, construction

took 12 years. Other historians place the start of the work in 304 B.C..

The statue was one hundred

and ten feet high and stood upon a fifty-foot pedestal near the harbour

mole. Although the statue has been popularly depicted with its legs

spanning the harbour entrance so that ships could pass beneath, it was

actually posed in a more traditional Greek manner: nude, wearing a spiked

crown, shading its eyes from the rising sun with its right hand, while

holding a cloak over its left.

No ancient account

mentions the harbour-spanning pose and it seems unlikely the Greeks would

have depicted one of their gods in such an awkward manner. In addition,

such a pose would mean shutting down the harbour during the construction,

something not economically feasible.

The statue was constructed

of bronze plates over an iron framework (very similar to the Statue of

Liberty which is copper over a steel frame). According to the book of

Pilon of Byzantium, 15 tons of bronze were used and 9 tons of iron, though

these numbers seem low. The Statue of Liberty, roughly of the same size,

weighs 225 tons. The Colossus, which relied on weaker materials, must have

weighed at least as much and probably more.

Ancient accounts tell us

that inside the statue were several stone columns which acted as the main

support. Iron beams were driven into the stone and connected with the

bronze outer skin. Each bronze plate had to be carefully cast then

hammered into the right shape for its location in the figure, then hoisted

into position and riveted to the surrounding plates and the iron frame.

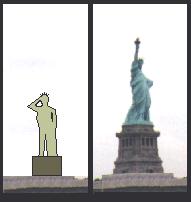

Comparing the Statue of Liberty with the Colossus:

Though the bodies are the same size the Statue stands higher because of

the taller pedestal and upraised torch.

The architect of this

great construction was Chares of Lindos, a Rhodian sculptor who was a

patriot and fought in defence of the city. Chares had been involved with

large scale statues before. His teacher, Lysippus, had constructed a

60-foot high likeness of Zeus. Chares probably started by making smaller

versions of the statue, maybe three feet high, then used these as a guide

to shaping each of the bronze plates of the skin.

It is believed Chares did

not live to see his project finished. There are several legends that he

committed suicide. In one tale he has almost finished the statue when

someone points out a small flaw in the construction. The sculptor is so

ashamed of it he kills himself.

In another version the

city fathers decide to double the height of the statue. Chares only

doubles his fee, forgetting that doubling the height will mean an

eightfold increase in the amount of materials needed. This drives him into

bankruptcy and suicide.

There is no evidence that

either of these tales are true.

The Colossus stood proudly

at the harbour entrance for some fifty-six years. Each morning the sun

must have caught its polished bronze surface and made the god's figure

shine. Then an earthquake hit Rhodes and the statue collapsed. Huge pieces

of the figure lay along the harbour for centuries.

"Even as it lies," wrote

Pliny, "it excites our wonder and admiration. Few men can clasp the thumb

in their arms, and its fingers are larger than most statues. Where the

limbs are broken asunder, vast caverns are seen yawning in the interior.

Within it, too, are to be seen large masses of rock, by the weight of

which the artist steadied it while erecting it."

It is said that an

Egyptian king offered to pay for its reconstruction, but the Rhodians

refused. They feared that somehow the statue had offended the god Helios,

who used the earthquake to throw it down.

In the seventh century

A.D. the Arabs conquered Rhodes and broke the remains of the Colossus up

into smaller pieces and sold it as scrap metal. Legend says it took 900

camels to carry away the statue. A sad end for what must have been a

majestic work of art.

|