|

Khufu's Great Pyramid

Workers finish one of the smaller pyramids at the Great Pyramid complex at

Giza.

It's 756 feet long on each

side, 450 high and is composed of 2,300,000 blocks of stone, each

averaging 2 1/2 tons in weight. Despite the makers' limited surveying

tools no side is more than 8 inches different in length than another, and

the whole structure is perfectly oriented to the points of the compass.

Until the 19th century it was the tallest building in the world and, at

the age of 4,500 years, it is the only one of the famous Seven Wonders of

the Ancient World that still stands. It is the Great Pyramid of Khufu, at

Giza, Egypt.

Some of the earliest history of the Pyramid comes from a Greek traveler

named Herodotus of Halicanassus. He visited Egypt around 450 BC and

included a description of the Great Pyramid in a history book he wrote.

Herodotus was told by his Egyptian guides that it took twenty-years for a

force of 100,000 oppressed slaves to build the pyramid. Stones were lifted

into position by the use of immense machines. The purpose of the

structure, according to Herodotus's sources, was as a tomb for the Pharaoh

Khufu (whom the Greeks referred to as Cheops).

Most of what Herodotus tells us is probably false. Scientists calculate

that fewer men and less years were needed than Herodotus suggests. It also

seems unlikely that slaves or complicated machines were needed for the

pyramid construction. It isn't surprising that the Greek historian got it

wrong. By the time he visited the site the great pyramid was already 20

centuries old, and much of the truth about it was shrouded in the mists of

history.

Certainly the idea that it was a tomb for a Pharaoh, though, seems in line

with Egyptian practices. For many centuries before and after the

construction of the Great Pyramid the Egyptians had interned their dead

Pharaoh-Kings, whom they believed to be living Gods, in intricate tombs.

Some were above ground structures, like the pyramid, others were cut in

the rock below mountains. All the dead leaders, though, were outfitted

with the many things it was believed they would need in the after-life to

come. Many were buried with untold treasures.

Even in ancient times thieves, breaking into the sacred burial places,

were a major problem and Egyptian architects became adept at designing

passageways that could be plugged with impassable granite blocks, creating

secret, hidden rooms and making decoy chambers. No matter how clever the

designers became, though, robbers seemed to be smarter and with almost no

exceptions each of the great tombs of the Egyptian Kings were plundered.

In 820 A.D. the Arab Caliph Abdullah Al Manum decided to search for the

treasure of Khufu. He gathered a gang of workmen and, unable to find the

location of a reputed secret door, started burrowing into the side of the

monument. After a hundred feet of hard going they were about to give up

when they heard a heavy thud echo through the interior of the pyramid.

Digging in the direction of the sound they soon came upon a passageway

that descended into the heart of the structure. On the floor lay a large

block that had fallen from the ceiling, apparently causing the noise they

had heard. Back at the beginning of the corridor they found the secret

hinged door to the outside they had missed.

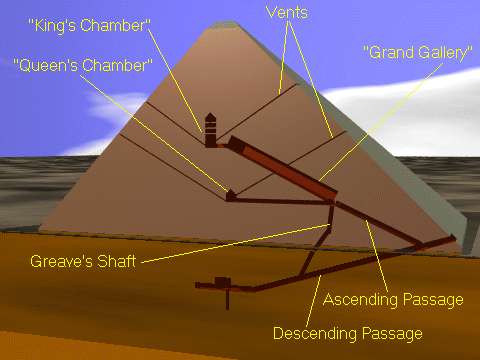

Working their way down the passage they soon found themselves deep in the

natural stone below the pyramid. The corridor stopped descending and went

horizontal for about 50 feet, then ended in a blank wall. A pit extended

downward from there for about 30 feet, but it was empty.

When the workmen examined the fallen block they noticed a large granite

plug above it. Cutting through the softer stone around it they found

another passageway that extended up into the heart of the pyramid. As they

followed this corridor upward they found several more granite blocks

closing off the tunnel. In each case they cut around them by burrowing

through the softer limestone of the walls. Finally they found themselves

in a low, horizontal passage that lead to a small, square, empty room.

This became known as the "Queen's Chamber," though it seems unlikely that

it ever served that function.

Back at the junction of the ascending and descending passageways, the

workers noticed an open space in the ceiling. Climbing up they found

themselves in a high-roofed, ascending passageway. This became known as

the "Grand Gallery." At the top of the gallery was a low horizontal

passage that led to a large room, some 34 feet long, 17 feet wide, and 19

feet high, the "King's Chamber." In the centre was a huge granite

sarcophagus without a lid: otherwise the room was completely empty.

The pyramids at Giza. The far pyramid is the "Great Pyramid." The middle

one looks larger, but only because it is built on higher ground.

The Arabs, as if in revenge for the

missing treasure, stripped the pyramid of it's fine white limestone casing

and used it for building in Cairo. They even attempted to disassemble the

great pyramid itself, but after removing the top 30 feet of stone, they

gave up on this impossible task.

So what happened to the treasure of King

Khufu? Conventional wisdom says that, like so many other royal tombs, the

pyramid was the victim of robbers in ancient times. If we believe the

accounts of Manum's men, though, the granite plugs that blocked the

passageways were still in place when they entered the tomb. How did the

thieves get in and out?

In 1638 a English mathematician, John

Greaves, visited the pyramid. He discovered a narrow shaft, hidden in the

wall, that connected the Grand Gallery with the descending passage. Both

ends were tightly sealed and the bottom was blocked with debris. Some

archaeologists suggested this route was used by the last of the Pharaoh's

men to exit the tomb, after the granite plugs had been put in place, and

by the thieves to get inside. Given the small size of the passageway and

the amount of debris it seems unlikely that the massive amount of

treasure, including the huge missing sarcophagus lid, could have been

removed this way.

Some have suggested that the pyramid was

never meant as a tomb, but as an astronomical observatory. The Roman

author Proclus, in fact, states that before the pyramid was completed it

did serve in this function. We can't put two much weight on Proclus words,

though, remembering that when he advanced his theory the pyramid was

already over 2000 years old.

Richard Proctor, an astronomer, did

observe that the descending passage could have been used to observe the

transits of certain stars. He also suggested that the grand gallery, when

open at the top, during construction, could have been used for mapping the

sky.

Many strange, and some silly, theories

have arisen over the years to explain the pyramid and it's passageways.

Most archaeologists, though, accept the theory that the great pyramid was

just the largest of a tradition of tombs used for the Pharaohs of Egypt.

So what happened to Khufu's mummy and

treasure? Nobody knows. Extensive explorations have found no other

chambers or passageways. Still one must wonder if, perhaps in this one

case, the King and his architects out smarted both the ancient thieves and

modern archaeologists and that somewhere in, or below, the last wonder of

the ancient world, rests Khufu and his sacred gold.

A cross-section of the Great Pyramid

showing the passageways.

|