Cessna

120/140

by

Budd Davisson, courtesy of

www.airbum.com

Stacking

Cessna's Littlest Against Other Classics

In 1946, when

factories were cranking-out little airplanes

like elves making cookies, Cessna didn't

want to be left behind. They had done their

own marketing studies and they too were

convinced a world awash in ex-military

pilots and GI's waving their GI bill checks

would want airplanes. Lots of airplanes.

They couldn't know how wrong they were.

Cessna, however, didn't

have a design ready to go, where most other

manufactures had been cranking out two-place

training/recreational aircraft before the

war. Cessna had to start from scratch.

Although it isn't known how much, or if,

they studied the Luscombe, there are too

many configuration similarities to think

otherwise. It would have to be assumed, they

at least took note of that pre-war

airplane's size, construction and success

and took off from there.

120/140 Model

Differences.

Let's start the conversation about

Cessna 120/140's off right by passing along

the phone and address of the Cessna 120/140

club. They are the people with all the

answers.

Cessna 120/140 Club

Dave Lowe-President

Box 830082

Richardson, TX 75083

(502) 736-5392

The littlest Cessnas are

not easy to tell apart and, for most of us,

it was a proud day when we finally

understood the subtle differences between

the three basic models of two-place classic

Cessnas, the 120, 140 and 140A.

First of all, the 120 and

140 were initially produced concurrently.

It's unclear, however, whether the 120 was

to be an economy model of the 140 or the 140

was to be the luxury version of the 120.

However significant the marketing department

thought the differences to be in 1946, the

gap has narrowed to zero, since most

consider the airplanes to be nearly

interchangeable. The 140A, however,

signalled a relatively major design

improvement.

The 120 and 140

All

Cessna 120s and 140s originally had fabric

wings, two steel struts and completely

aluminium structure. A few have had the

fabric replaced with metal in the half

century since their birth. In fact, a few of

the airplanes were even converted to

tricycle gear. Don't ask why, we don't

understand either. Both airplanes had the 85

hp Continental, although the 140 had an

electrical system as standard equipment.

These days it's seldom a 120 is seen without

an electrical system. However, it's a fact

that a straight, clean 120 sans electrical

will out fly the rest. In little airplanes,

weight is everything.

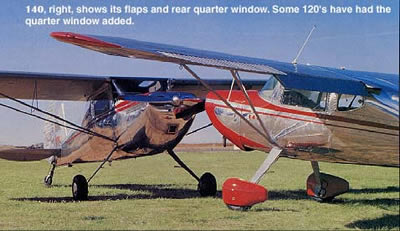

The visual differences

between the two models include items which

only the 140 has: the rear quarter windows

and long, skinny flaps. We'll discuss the

flaps later, but they shouldn't be the

deciding factor between buying one model or

the other. Then, as if things aren't

confusing enough, a lot of 120s have

magically sprouted the quarter windows of

the 140.

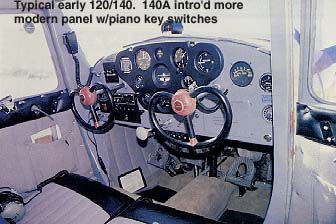

140's received an

up-dated instrument panel in 1948 which

eliminated the "old-fashion" looking central

cluster of instruments. A new floating panel

spread the instruments across the cockpit.

Radios are usually mounted left of the

pilot's control yoke.

Cessna 140A

The "A" model was introduced in 1949,

presumably in an attempt to jump-start

flagging sales. An estimated 525 were built,

including a small number of "Patroller"

versions with Plexiglas doors, 42 gallon

tanks (!) and a message tube though the

floor. The fuselage remained the same, but

the wings were completely redesigned for the

140A. The blunt, rounded planform

disappeared to be replaced by an even more

"modern" appearing semi-tapered shape. When

Fowler flaps were later added, these were

the wings which would be used on the

still-to-come 150s. The C-85 was replaced

with a C-90 in the 140A.

140A wings are

stressed-skin aluminium, which eliminates

the need for the second strut. This is why

"A" models have a single, aluminum strut.

The ailerons run the entire length of the

tapered section and the tips are squared

off. The flaps were shortened, but are

several inches wider than straight 140 flaps

and seem to be a little more effective.

"A" model landing gear

legs are swept forward to place the wheels

further ahead of the CG than on the earlier

airplanes. This was done to protect the

airplane from pilots transitioning out of

other two-place airplanes who had never

flown with toe-brakes. This is why it's

common to see 120/140's with steel

extensions bolted to the gear legs which

move the wheels ahead about four inches.

Many consider this to be overkill, as the

brakes have to be hit fairly hard to make

the tail come up. It's a training problem

more than a hardware design flaw.

Mechanical Description

If you want to know how a 120/140 is

built, look at a C-150/152. Structurally,

with the exception of the welded steel

struts of the 120/140s, and the fabric

covered wings, they are almost identical.

The spring steel landing

gear of the 120/140 was the first

large-scale application of Steve Wittman's

patent and it obviously worked. There have

been a few incidents of gears cracking

through the rivet holes (many are now

bolted) which hold the steel steps in

position but a simple Zyglo test will show

if there are problems there.

Other than corrosion

problems typical of all old aluminium

airplanes (along the rear spars or anywhere

which can trap gravity-driven condensation),

the airplanes have been relatively free of

mechanical maladies. The most common

problems include cracked elevator hinges and

an occasional cracked rear fuselage

bulkhead.

The brakes are one area

of concern. The originals were Goodyears

with floating disks held in alignment with

spring clips. They used small, round brake

pucks which have gotten terribly expensive

and many owners machine down automotive

pucks to fit (ssshhhh, the feds might hear).

A much bigger worry is the possibility of a

brake locking, if a retaining clip is lost

and the disk cocks over and gets jammed.

Converting to McCauley or Cleveland brakes

is the usual fix.

Incidentally, because of

the outside storage and general age of the

airplanes, their wiring bundles are

sometimes frayed and brittle. Check all

wiring carefully.

A note about the

airplane's mechanical character: This is an

airplane that responds beautifully to TLC

and elbow grease. Everything about it is

easy to take apart for cleaning and

painting.

Flying Characteristics

Each classic airplane has its own flying

personality and so does the 120-140. It's

important to remember it's a post war

design. Most of its contemporaries were

originally designed before the war to

perform on the A-50 or A-65 so they are

smaller and lighter. The C-120/140 is a

bigger airplane and is a little heavier

feeling and flying than something like a

Luscombe or a Taylorcraft. It doesn't feel

quite as much like a maple seed in the wind,

as do some of the others. Make no mistake,

however, it is still a very light airplane.

Depending on the model, they'll weigh-in

empty at 950-1000 pounds and gross at 1,425

pounds (525 pounds useful).

The first thing you'll

notice on boarding a 120/140, is that

getting in isn't much of a hassle. Although

some purists de-cry the use of control

wheels rather than sticks, having the floor

free of obstacles does ease entry.

Once in, the next thing

you notice is that seeing over the nose is

possible with only a slight stretch. With a

cushion behind them, the average-height

pilot can see the centreline without

stretching. The cockpit is slightly narrower

than the latest C-152, but about the same as

its contemporaries. This makes it fine for

the FAA-standard 170 pound pair but gets

crowded rapidly as crew dimensions increase.

Unless converted to key start, the airplane

has a separate pull-to-start handle which,

to a pilot used to modern Spam cans, seems

unusual. Once the engine is running, the

straight exhausts are evident even at idle.

On takeoff they really bark. It's hard to

believe we all used to fly these without

headsets, as a matter of course. No wonder

we're all half-deaf.

If the tailwheel is in

even remotely good shape, the airplane will

taxi nearly as effortlessly as a nosewheel

airplane, needing an occasional tap on the

brakes to make sharp corners. The excellent

visibility makes it that much easier.

Take-off performance is

directly related to the amount of weight on

board. As with all lightly wing loaded,

low-powered airplanes, the two-place Cessnas

are different airplanes solo or dual. In no

case, however do they float off the ground

like a Cub or Luscombe. Actually, they

takeoff remarkably like a Cessna 152,

although without as much ground roll.

When the tail is raised

during takeoff, the spring gear is

immediately noticeable because it doesn't

have the solid feel of a bungee gear and

"wallows" just a little. Here, it feels

almost exactly like a Citabria and for the

same reason. If the wind is on the nose, the

airplane will track almost perfectly

straight. It will, however, try to gently

turn into a crosswind. A little rudder

pressure takes care of that.

If the crosswind is a

real howler, the pilot will have to work to

keep the wing down because the ailerons

don't get effective until there is a fair

amount of wind going across them. Somewhere

around 25-30 mph, they start coming alive.

The handbooks

say a Cessna 140 will climb at 700 fpm at

sea level and gross weight. There are

probably some that will do that, but most

are closer to 500-600 fpm in that situation.

As density altitude increases expect climb

to go down accordingly. Most pilots use fuel

load as the variable factor. With 22 gallons

usable and a fuel burn of only 5 gallons per

hour, leaving 60 pounds of fuel on the

ground, still gives a two-plus hour

endurance and affects climb performance

noticeably. Here again, overall performance

is in the ball park with the C-152.

The climb and cruise

performance of 120/140's varies drastically.

The primary factors are propeller installed

and weight, with rigging coming close

behind. 100-115 mph is the normal range.

With a climb prop, which is good for at

least 100-150 fpm extra climb, expect to be

at the bottom of the speed range. The

cleaner airplanes with a cruise prop will

easily touch the top end, 115 mph. Weight

also changes cruise drastically. It's not

unusual for an airplane to give up 10 mph to

carry an extra person and full fuel.

In cruise, the airplanes

are among the most comfortable and stable of

the breed. Visibility is excellent,

although, with your eyes just barely below

the wings, it's a good idea to raise the

inboard wing to clear before turning. Once

the airplane is "on the step" and trimmed,

it'll fly a straight line until running out

of fuel although it will ride the tiniest

thermals. Of the airplanes of its type, it

is one of the more stable cruisers,

primarily because it is heavier. It also has

some of the best over-the-nose visibility in

cruise. A headset, however, is mandatory for

comfort and hearing protection.

When landing, thermals

aside, the airplane will hold approach speed

reasonably well if trimmed to it. If the

pilot tries to hold speed by hand, rather

than trimming, however, the airplane seems

to want to pick up speed. At 60-65 mph on

final the airplane gives the pilot all day

to set up the approach. Also, compared to

something like a Cub, it is a lousy slipping

machine. In fact, if you don't get the speed

down to around 65, a slip has almost no

effect.

Most 140 pilots don't

bother with flaps on landing because they

have only a marginal effect. They do

increase drag slightly and kill just a

little float. 140A flaps seem more effective

and worth using.

A three-point landing is

almost a non-event, as long as the airplane

touches down straight with no drift. Even if

put on crosswise, however, the airplane just

jumps and jiggles and has little tendency to

swerve quickly. This is one of the strong

points of the spring gear. It is very

forgiving of misalignment on touchdown. Even

if the airplane does decide to head for the

bushes, the rudder is quite effective and a

quick punch is generally all that's needed

to set it straight. It is only marginally

more demanding than a Cub and about the same

as a lightly loaded Citabria.

Wheel landings take a

little getting used to because the airplane

seems so close to the ground. If the pilot

just tries his best to hold the airplane

barely off the ground, letting it find the

runway itself with no help from the pilot,

it will roll on smoothly. If the pilot tries

to "help" it find the ground with a gentle

push, a bounce is in the offing. Fighting

the urge to push is the most important

ingredient of a wheel landing with spring

gear.

The Cessna 120/140 series

has always brought a premium price in the

two-place classic pack for a reason. The

airplane's near-modern utility combines with

a structure that can weather the elements in

outside storage better than most to make it

very attractive. This is an airplane with a

foot in both camps; classic and contemporary

and combines the best of both.

|