Classic is as Classic Does

It is dangerous to use the

word "classic." One reason

is that, under the EAA's

scheme of things, the term

applies to a specific

group of airplanes made

after the war. For

another, it denotes

something that is timeless

which knows no era of

birth or death. That is

the traditional definition

of the word, and it is

usually applied to a work

of art whether one, two,

or three dimensional one

that will live forever.

It's also 'the definition

of the Ryan STA.

I am a

STA buff, pure and simple.

I am not an expert. I have

very little Ryan time and

I doubt if I've seen more

than three STAs in my

entire life. But that

can't stop me from loving

a celebrity I've never met

or a place that I've never

been. In that respect, I

suppose I'm like ninety

percent of the aeromaniacs

around the world. You

don't have to have flown

an STA nor do you even

have to be a pilot to

appreciate the lines and

the history of performance

that has made the STA live

well beyond her prime of

life. No, correct that,

because she is still in

her prime of life, which

is why she is a classic.

If I

were being totally honest,

I would have to admit to

an unnatural lust for the

STA; in my eyes, there is

simply no better looking

open-cockpit monoplane. In

fact, most of my Veco

Chiefs and Warriors (those

are control line models to

you for young'uns out

there) came out looking

like STAs. But, if you

think about it, most of

the control line models of

the 1940s and 1950s tried

to look like STAs since

that was every kid's way

of owning the airplane

they all loved.

I've

never owned one nor will

I, a simple matter of

economics because the Ryan

has never been cheap

airplane. Costing $6,000

in its 1938 version, there

was a brief period right

after the war where a few

surplus STMs (military

STAs) showed up at bargain

basement prices. That,

however, was only the

briefest blink of

history's eye because she

has always been one of the

more expensive "antique"

airplanes around. Today

she commands prices in the

$50,000 bracket.

Designed originally in

1934 by T. Claude Ryan, he

of Spirit of St. Louis

fame, the plane first

took to the air as the S-T

with a little 95-horse

Menasco four cylinder,

in-line engine in the

nose. After only four or

five S-Ts were produced,

the engine was replaced

with the 125 horse C-4

Menasco which gave it a

lot more performance and

quickly grabbed the

attention of such

aeronautical luminaries as

Tex Rankin who used an STA

to win the International

Acrobatic Championships in

1938. According to

folklore, Rankin used to

dive the airplane to 260

miles an hour to start

some of his manoeuvres

which, if true, certainly

proves the fact that there

were no real structural

limitations on the STA

airframe. The only

limitation was the pilot's

intestinal fortitude.

Since the STA attracted

the so-called "sportsman"

pilots of the day, it was

only natural Ryan would

produce a hotrod model STA

called simply STA Special.

It was the supercharged

150 horse C-4S Menasco

that made the STA Special,

really special. That extra

25 ponies gave a top speed

of 160 miles an hour

(according to yellowed

pilot handbooks) along

with acrobatic performance

that was hard to match.

Which

brings us to STA Special

Serial No.188 and Lou

Russo.

Lou has

owned No. 188 for

something over twenty

years and, for at least

half of that time, he and

I have been trying to get

together so I could live

out my Ryan fantasies for

real. But even though he

bases the airplane less

than 80 miles away,

somehow we just never seem

to dovetail our schedules

or weather. Finally, just

before he changed job

locations, which would

have taken his STA away

from me forever, we

managed to meet at

Andover-Aeroflex Field in

New Jersey where I am

based.

As I

watched him come down

final to the stubby little

2,000-foot runway I call

home, I was more than just

casually observing. I was

analyzing his approach and

his way of handling the

airplane since I knew in a

few minutes that would be

me up there. I didn't want

to blow this one

opportunity that had

eluded me for so long. As

he gently touched down and

rolled to a stop in less

than half the runway,

visions of Veco Chiefs and

all the film clips I had

ever seen of STAs dancing

through the sky flashed

through my mind and I

couldn't help but grin. I

just knew that I was going

to love this. I felt as if

I had known the airplane

all my life.

There

is bound to be an

inevitable comparison

between the PT-22 world

war two trainer And the

STA since they are of the

same lineage and general

configuration. I am not

particularly in love with

PT-22s but I had always

heard there was a giant

difference between the 22s

and the STAs. I noticed

some of the physical

differences as soon as I

started to saddle up No.

188. Certainly the most

noticeable is the size of

the cockpit opening. Most

of the military model

Ryans (STMs, PT-20, -21s,

-22s, etc.) moved the

fuselage stiffeners to the

outside and down so as to

allow a much larger

cockpit cut-out so cadets

could climb in and out

with that infamous

cement-hard seat pack

parachute. Also, the STA

had heel brakes (more

about those later) instead

of the 22's toe brakes

while the windshield was a

formed, highly streamlined

fairing made to cheat the

wind while protecting the

pilot. The landing gear

was a full foot wider on

the 22 and used gigantic

castings rather than steel

weldments for the yokes.

The fuselage on the 22 was

14 inches longer and 3

inches wider. Oh yeah, I

forgot the most obvious

change, the little C-4S

Menasco apparently wasn't

giving the military the

reliability they wanted so

they went to a Kinner 160

horse radial. The net

result of militarizing the

STA airframe added almost

300 pounds to her empty

weight, nearly thirty

percent over the STA's

1,050-pound empty weight.

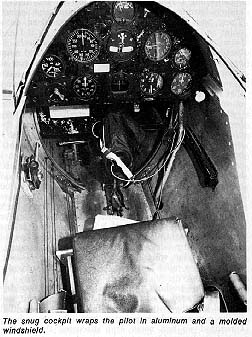

A lot

of old airplanes feel just

that, old, but the STA

envelops you in a tight

little aluminium womb that

makes an old Pitts pilot

like me feel right at

home. Only the

aforementioned heel brakes

were of any real concern.

They pivoted off of the

bottom inside corner of

the rudder pedals,

requiring you to swing

your heels well inboard

and up to use them. This

would be no real problem

except I was wearing

cowboy boots with riding

heels and I had to work

especially hard to make

sure I didn't slip off the

brake pedals. Since the

airplane has a full swivel

tail wheel, the ultimate

authority in steering once

the wind is gone out of

the tail is the brakes.

In

taxiing through the grass

toward the end of the

runway, I was pleased (and

relieved) to find that

with just idle power and

virtually no forward

speed, the rudder had

absolutely no trouble

steering the airplane. The

brakes were only for

stopping and not for

directional control.

Lou

made the first takeoff and

I observed his technique

carefully. When it came my

turn, I brought the stick

forward just as quickly as

I moved the power up

getting the tail into the

air almost before we were

rolling. The engine had

that flat, hard bark that

only comes from short

exhaust stacks on in-line

cylinders. It's a world

away from a Lycoming or

even a radial. It's a

sound all it's own.

A

little rudder pressure

here and there kept that

long, narrow cowling

pointed straight down the

middle of the runway. I

felt that familiar grin

work its way across my

face, as the airplane

lifted off and began

climbing in a near level

attitude. The wind nipping

at my helmet, the stick

vibrating in sympathy with

the Menasco, the airplane

had an aura of graceful

eagerness to it, as if it

was reacting to your

wishes, rather than being

forced to go somewhere it

didn't want to go.

Leaving

the go-lever forward, I

brought the nose up

searching for 80-85 miles

an hour and found another

gigantic difference

between the STA and the

PT-22 . . . the STA really

knows how to climb! Since

No. 188 was a Special,

that extra 25 horses

probably did wonders to

her takeoff and climb

performance. Since I'll

probably never get another

chance to fly a straight

STA, my memories of its

takeoff performance will

always be that of the STA

Special.

We

weren't even out of the

pattern and I knew I had

definitely not misplaced

my affections for the last

thirty-five years. She was

everything I had hoped she

would he.

Russo

and I were both very, very

pressed for time, so the

time allotted for me to

make the STA's

acquaintance was much

tighter than I would have

preferred, but I still

felt as if I was being

allowed to poke my head

into airplane heaven. As I

pushed the nose over into

cruise and the speed built

up, I began doing Dutch

Rolls to get a feel for

the rudder/ aileron

harmonization. . it was

absolutely perfect. There

was no problem keeping the

nose dead on a point as I

rocked from side to side.

It was as if I had been

doing this for years

because the controls

flowed together so nicely.

The ailerons were quicker

and more precise than I

had even imagined.

Although not as quick as a

Swift or a Pitts, in its

day the STA must have been

a real mind breaker. The

only contemporary that had

similar controls was the

fabled Bucker Jungmiester,

another of the legends to

come out of the 1930s.

On the

ground, even before Lou

walked around up front to

yank the engine into life

he apologized for his

airplane being out of rig.

While I did notice a

slight wing down tendency

in cruise, it wasn't until

bringing the power back to

set up for a stall that I

really noticed what he

said. As the needle

dropped below 50 miles an

hour and the wing decided

it had had enough, the

nose dropped and the

airplane rolled briskly to

the left demanding that I

push the nose down and

punch the Menasco.

Instantly it was back

flying again, so I brought

the nose up and set up for

another stall, this time

out of a 20-degree bank to

the left. Pulling controls

a little hard produced an

accelerated stall that,

again, dropped the left

wing sharply down, showing

me that, if I wanted, a

quick spin entry was only

a little rudder pressure

away.

With time working against

us and the sun working its

way toward the horizon, I

turned around and headed

into the pattern at

Aeroflex. As I was

parallel to the runway and

preparing to bring the

power back, I realized we

had never even discussed

the landing and I had no

idea what approach speed

to use. Theorizing that

airplanes generally glide

at the same speed at which

they climb best, I brought

the power back and set up

an 80 mile an hour glide.

Later, Lou told me I had

been right on the money,

so guess-work once again

replaces talent. The

airplane's clean lines

fooled me because it was

obvious the STA wasn't

losing altitude at the

rate I had expected. A

slight slip was in order.

I had forgotten the

airplane had flaps, which

may have helped in that

situation, but I prefer a

slip anyway.

At no

time did the nose block

out any of the runway, not

even as I broke the glide

and gently felt for the

grass with the main gear.

Again, guessing that it

probably safer to wheel

land the airplane, as I

had seen Lou do, I held a

level altitude gently

holding off until that

long stoke-gear kissed the

grass ever so slightly,

and I gently eased the

stick forward to pin the

STA into position.

As on

the takeoff, just the

gentlest of rudder

pressures kept the nose

dead in front of me.

However, as the wind began

to go out of the tail and

I let the plane come down

into a three point

position, it suddenly

dawned on me that I

couldn't reach the brakes

with my heels! I moved

around for a few seconds

fishing for the brake

pedals and finally said

the hell with it and

brought my head inside the

cockpit to see exactly

where my feet and the

brake pedals were. I

located them just in time

to help me slow down a

meandering swerve that had

developed while I had my

head between my knees.

On the second takeoff and

landing, I felt even more

at home except I once

again was high on the

approach and no amount of

slipping was going to get

me down in the first 500

feet of the runway. You

get in the habit when

flying off a 2,000 foot

strip of going around if

you haven't got it down

right where you want it

and that was the case on

this approach . . . go

arounds happen in the best

of families. On my third

approach I had enough

sense to back the STA out

a little further and Lou

ran out the flaps which

helped even more. Knowing

this would probably be my

last landing in an STA, I

was determined to make the

touchdown as smooth and

perfect as possible, since

that's the memory I would

always carry. Before I

broke the glide, I glanced

inside to make sure my

heels were on the brake

pedals should I need them

and then gently held off

as the wheels whispered

through the grass. As they

began to settle on, I

again pinned it to the

runway and felt that silly

grin working its way

across my face for the

umpteenth time on this

trip. This time I had it

wired and made an arrow

straight roll out, which

was much more of a tribute

to the airplane than the

pilot.

The

comment a person makes

when they un-strap an

airplane after they've

flown it for the first

time often reveals much of

what went on during the

flight. In this case, the

first thing that came to

mind as I climbed over the

side of the fuselage was

"Lou, I now see why

everybody loves STAs."

So

what's not to love? The

STA is a beautiful machine

with some of the best

control harmonization to

be found in airplanes of

the period. The visibility

in takeoff and landing is

excellent, considering

that it is a taildragger,

and in a wheel landing

she's dead easy to handle.

However, Lou says in a

three-point, the Ryan does

have a tendency to wander

one way or the other and

he prefers to always put

the plane on its main gear

as a form of insurance.

I know

for a fact that I will

never own an STA. The

economic gods have willed

that things like college

payments and houses have

to come first. It's not as

if I haven't been there,

and that at least puts me

several notches up the

totem pole of dreams. I

was probably ten years old

when I fell in love with

the machine, and it took

thirty-three years to

consummate that romance.

A

classic? Yes, in every

possible sense of the

word. She'll undoubtedly

live on forever.

'Who

knows? Maybe I'll own one

yet.