AT-6

by Budd

Davisson, courtesy of

www.airbum.com

School Marm

With an Attitude

Connie Edwards,

long time sparkplug of the warbird movement

and quintessential Texan is credited with

saying, "Start out in a Bearcat, transition

to the P-51 and then you're ready for the

T-6."

Edwards was referring to

the T--6's less-then-spotless reputation for

ground handling. And he's right. Many

civilians transitioning into fighter

aircraft are amazed at how much easier

fighters are to handle (in most situations,

anyway) then the old Texan, a supposedly

easily-tamed "trainer." When I got my chance

to fly Mustangs, I was amazed and relieved

to find this was absolutely the case. If the

P-51 had been the quantum jump up from the

T-6 in ground handling difficulties that it

was in aerial performance, my first Mustang

hop would have culminated in a spectacular

fire at the edge of the runway. Even if I

kept control and survived the flight, I

would have drowned in post-flight adrenaline

flow. Obviously it didn't happen that way

because the Mustang was such a pussy cat

compared to the Texan.

I can't speak for others,

but the Six had me so wired for abysmal

ground handling that the Mustang was a

breath of fresh air. There was nothing that

big bird could do that would surprise me.

Yes, "relieved" is definitely the right

word.

My reaction to the Six

was probably typical and definitively

indicative of what the old school marm

represents...the epitome of the

higher-performance trainer. It wasn't

supposed to be easy to fly. It was not,

repeat not, supposed to take a student out

and give him a good time. By the same token,

the Texan wasn't supposed to present him

with impossible tasks either. And it didn't.

What the AT-6 (SNJ to you Navy types)

represented, and still represents, was the

finest combination of challenges ever built

into a military trainer. The student had to

fly the airplane, reading its every nuance.

His proficiency benefited from this mental

and physical exertion. He got better whether

he wanted to or not!

The best

indication of how good a trainer the Texan

was/is can be seen by the fact that here we

are forty years into the jet age and there

are still countries around the world using

the North America aerial classroom as

first-line trainers. As recently as five

years ago, major air forces still used it

and it is the updating of those air forces

which has pumped so many surplus T-6s into

the American civilian market.

A specialty industry has

developed to support and sell the T-6/SNJ/Harvard.

Part of this industry has worked to bring

back as many Texans as possible from

overseas where they are being retired. Ray

Stutsman of Elkhart, Indiana brought back a

herd or two of Spanish T-6s while others are

working on bringing back the South African

birds. Prices vary wildly, ranging from

$20,000 to $60,000 with $30-$35,000 giving

you a fairly clean airplane with lots of

time left on the P&W R-1340. As is usually

the case, you get what you pay for.

(Editor's Note From the Year 2000: Budd, you

dummy, you should have bought a couple

dozen, when you could. Just quadruple those

prices and you'll be close to today's

prices)

I am not a high-time

Texan driver. Without digging through logs

and adding up all the numbers, I'd say my

time spent in the cavernous cockpit would

barely top 100 hours, all of it civilian. Of

that time, at least half was in the back

seat either receiving dual time (in

preparation for bigger birds with longer

noses) or giving dual to Texan owners who

wanted to know how to land/spin/aerobat

their airplane. I'm not the definitive

authority on T-6 performance and handling. I

am, however, pretty typical of the average

civilian pilot who is lucky enough to find

himself strapped into one of the biggest

pieces of iron commonly available to us. My

viewpoint is grassroots . . . and reasonably

current.

Oddly enough, I'm not

sure where I flew my first T-6. It may have

been the D model operated by Flight Safety

out of Vero Beach, Florida. But while I'm

hazy where my first T-6 time came from,

there's no doubt where I spent the most

instructive time in the Texan: at Junior

Burchinal's Warbird school in Paris, Texas,

during the early 1970s. I've put a lot of

time into T-6s since then and I've enjoyed

all of them more than I enjoyed those with

Junior. I can, however, guarantee I've never

learned more than in those ten hours with

Junior. He believes firmly in working your

buns off for your own good. And it worked.

When you climb into the

front hole of the T-6 it feels like a

fighter. I've said this before, many times,

but it's true. And one reason it feels like

a fighter is because North American designed

the Texan to give the student the feel and

controls of a big bird with less speed and a

more forgiving nature.

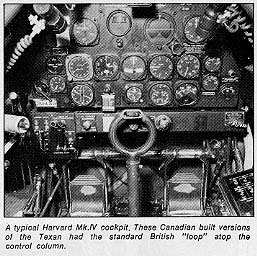

Describing the cockpit of

a T-6 is like describing a cockpit of most

World War Two fighters (especially North

Americans), although it is quite a bit

larger than something like a Bearcat.

Beneath your left arm are all of the primary

accessory controls, i.e. elevator, aileron,

and rudder trims, as well as the landing

gear and flap actuators. All of the

electronic and radio goodies are on a

console by your right arm.

You have to dig deep to

find the visual differences between a T-6

and SNJ and to differentiate the models of

Sixes, which the Air Force, adopted. One

sure clue of a SNJ or an early T-6 is a tail

wheel lock sticking out of the left side of

the canopy rail. Later T-6s had steerable

tail wheels similar to the Mustang, which

unlocked when you pushed the stick forward.

Supposedly this feature was on later Ds, all

Gs and the Canadian-built Harvards IV's

while earlier models and all SNJs had tail

wheels that were either locked straight

forward or free swivel depending on the

position of the control in the cockpit.

Another noticeable difference in the later

airplanes is the lack of a large cutout in

the upper right hand side of the instrument

panel; In SNJs and earlier model Sixes, a

provision was made to mount a .30 caliber

machine gun and the receiver stuck through

the instrument panel. The later airplanes

also eliminated the inertia starter, so the

energize and engage pedal between the

rudders may or may not be there. SNJ's and

early airplanes also have a separate

hydraulic actuation lever by your left knee.

In actuality there were a

ton of minor differences between all the

models but only the steerable tailwheel and

the late model servo-tabs on the ailerons

(which really do make the airplane much

nicer to fly) are noticeable.

Cranking up a round

engine is one of the world's true sensual

delights and it's made even more so if an

inertia starter is being used. The whine of

the starter winding up and the descending

mechanical growl of engagement are right out

of a late night movie sound track. And, of

course, as the engine coughs into life,

blowing smoke and noise past your elbows,

which are sticking out over the canopy

rails, the mechanical nostalgia gets even

deeper.

Canopy back, "S" turning

your way out to the runway, there's no doubt

you are working with a big piece of iron. As

you roll out on to the centerline, double

checking to make sure the tailwheel is

locked, you bring the power up smoothly and

wait for the 600 horses to start shoving all

that sheet metal down the runway. Many

airplanes accelerate much faster than a Six

and because of sheer size the Texan feels

almost as if it is lumbering along. Your

visibility isn't nearly as bad as expected,

only the centre portion of the runway is

blocked, so it is relatively simple to ease

rudder one way or the other to keep tracking

straight.

As

soon as the power is against the stop, the

tail is picked up gently (repeat, gently)

and the airplane will fly off with little or

no provocation from the pilot who thinks

he's in command. Hoist the tail vigorously

and you'll get a surprisingly quick swing to

the left as the gyroscopic precession of the

prop kicks in.

At this point I always

have to remind myself what model of Six I'm

flying, since retraction of the landing gear

requires an extra step in the earlier birds.

In the late models, you just jerk the gear

handle (that's down by your left knee) in

and up. In earlier Sixes and most SNJs,

however, you have to first activate the

hydraulic system by pushing down on a power

lever which gives you juice for something

like thirty seconds. At least once I thought

a T-6 was a real turkey in climb, then

looked down at my shadow and saw that the

gear was still out. Dumb!

Setting up climb power at

30 inches and 2000 rpm you can just sit back

and watch as the world gradually falls away.

While the rate of climb isn't going to do

much to amaze you, the feeling that comes

over you will. You find yourself drifting

into a military mental mode, since there is

nothing about the airplane that even vaguely

reminds one of a civilian airplane.

Absolutely nothing! The Texan is hardcore

military and the only difference between the

Six and a fighter is the number on the

airspeed gauge is much lower. Numbers are

only numbers. If you don't have telephone

poles whizzing past to give numbers some

scale, they are totally abstract, so you can

play fighter pilot to your hearts content in

a Six.

I dearly love to aerobat

the Six, although I'll have to admit that

since my chicken quotient is much higher

than my talent quotient I keep a healthy

amount of air between me and the hard stuff

below . . . like 6,000 feet for instance. At

that altitude, a Six will only be indicating

160-170 mph (depending on how clean the

airplane is and how much the airspeed lies),

so I'll drop the nose and get 180 on the

clock while centering a point on the horizon

in the windshield. Rolling forty-five

degrees to the right, I pull the nose up

into a giant barrel roll to the left,

keeping my reference point dead in the

centre of the roll. The Six loves those

kinds of manoeuvres . . big smooth ones.

It's so stable in all regimes that it

literally grooves through rolls as if on

rails.

The loops are the same.

The Six seems like it takes forever to find

the way up and over the top, chugging away

like a locomotive headed for Peoria.

The T-6 has some good/bad

habits that make it an excellent trainer.

One of these is the ability to unload in an

accelerated stall, if you don't pay

attention to the almighty airspeed/G-force

relationship something I always keep in the

back of my mind when I'm twisting the

airplane's tail.

The Texan stalls clean

somewhere in the neighbourhood of 70 mph but

the addition of G and/or bank angle can run

that up rapidly. I love to show students

that capability by pulling a bit too hard on

the top of a loop. The airplane will gently

stall and do a half-snap to right side up

and will continue into a spin if you wait

too long to release the back pressure.

You can see the same type

of stall performance in a tight turn. I have

the student pull into a tight turn to the

left, increasing back pressure as the speed

burns off. Somewhere along the line the

airplane will decide it's had enough and do

a half snap to the outside (if the ball is

centered) in one of the prettiest vertical

reverses you've ever seen. If the ball is

shoved to the outside, however, the Six will

snap to the inside and you'd better have a

little altitude to recover.

Accompanying

this ability to unload when you least expect

it is a definite appetite for secondary

stalls. If you spin the airplane or stall in

any way, you absolutely have to allow time

to accelerate and not put on any G until the

Six has enough speed to support flight. It's

really easy to accidentally spin the

airplane while dog fighting and get anxious

on the recovery, causing a secondary stall

and a spin in the other direction. This has

killed more than a few experienced pilots

who are goofing around without the

obligatory cushion of extra altitude.

Don't construe

these stall characteristics as being bad.

Yes, the T-6 will bite you but it will do so

the same way every time. It's totally

predictable. You get slow and pull and the

Texan lets you have it right now! Those

areas where the Six tends to get fiesty are

those areas where light handed flying is

required. A little attention to the speed/G

relationship will keep you out of trouble

all together. In other words, you have to

learn to fly the airplane . . . which is the

true test of a trainer in the first place.

One of the neatest things

about the Texan is to be sitting there just

chugging along at altitude, pretending the

world is still at war. You are surrounded by

a flat-black and zinc chromate green world

that's awash in a sea of cryptic placards.

You sit quite high in the airplane, well

over the nose, and you are very conscious of

protruding up into a greenhouse enclosure

with cockpit framing everywhere you look.

Your feet are stretched out to either side

of the stick, resting in giant trays with

equally giant rudder pedals at the forward

end. Even the simplest task, like checking

the fuel, reminds you that you are astride

an anachronistic military animal . . . the

fuel gauges are on the floor on either side

of the seat. Often you have to shade your

eyes to see down into the bowels of the

airplane.

Every time I get ready to

land a Six I can feel my mouth start to turn

to dust, a trait experienced Six drivers say

is good. At least I'm not over-confident (an

understatement), since most of the Six's

reputation for being cantankerous comes from

the landing phase.

Throwing the gear out on

downwind, you check the gear lights, but you

also squint to see through little plexiglass

windows on the top of each side of the wing

center section. It's only by checking to see

that the locking pins are secure that you

know for sure the gear is locked down. Then

you set up what is fairly normal approach

planning to have 90 mph on final, by which

time you'll have all 45 degrees of flap out.

The flaps are split trailing edge affairs

rather than true-hinged surfaces, so they

generate as much drag as they do lift. This

puts your nose down and gives you tremendous

visibility on final.

As a normal

rule, I'll opt for a three-point landing and

I slide my feet up high on the rudder pedals

to give mechanical advantage on the brakes

should I need them. Actually, the only

assumption you can make about a T-6 at all

is that it is going to swerve one way or the

other and you can't be sure which way. So

you plan accordingly, getting your nerves

and feet ready to handle whatever it dishes

out. The results of a bad swerve can be

really exciting-like crumpled wings, folded

landing gear, etc. If you do it really

right, you'll be awarded with a view of the

airport from an upside down position

alongside the runway. The trick is to catch

the swerves right at the beginning while

they are still tiny turns. Nip each of those

in the bud and the airplane is absolutely no

problem. It only gets nasty, if you let the

nose wander too far before getting your feet

in the act.

The machine wheel lands

quite easily, which is what most folks do

these days. However, the swerving tendency

is still there and you have to be wide awake

as the tail settles because it just loves to

meander as the wind goes out of the rudder.

I've always found G

models and Harvard Mk. IVs easier to land,

probably because of the steerable tail-wheel

but that may be an illusion brought about by

coincidence and luck.

A lot of folks think

they'll never get a chance to fly a real

Warbird. With the numbers of actual combat

aircraft dwindling down to nothing, it's

easy to overlook the fact that there are

between 500 to 600 T-6s running around the

country. That number is increasing everyday

and the T-6 is just as much Warbird as

anything that totes along a half dozen .50

calibres. More important, you can go a

lifetime without finding a Mustang owner

willing to give or sell you a ride. But the

possibility of some free fuel and a couple

of cool ones can tempt many a T-6 owner into

letting rag legs like you and me into the

backseat. There you aren't cooped up in a

hot, sweaty, noisy, little box as you are in

the back of a P-51 . . . strictly a

passenger in a cement mixer. In the back of

a T-6 you are still a pilot and can actually

fly the airplane. You can put your hands on

forty years of history and get a feel for

the way it was.

One note of caution: like

any Warbird the T-6 is a high-performance

machine possessed of high-performance quirks

and maintenance. So don't go up with just

any T-6 driver since the law of averages

says there's bound to be at least a few who

don't get enough time to stay truly

proficient. Don't be afraid to ask around

before jumping in with someone who may or

may not be as good as he or she thinks they

are.

In a T-6 you get the same

nostalgic rush most Warbirds give, only the

raw edged performance is missing. Most of

that performance, however, is measured only

by numbers on a dial.

Maybe T-6 owners should

repaint their airspeed indicators! |