Wrong

on both counts!

Walk in

the door of Bill and Judy

Zivko's company, Zivko

Aeronautics, Inc, on

Guthrie Municipal

northeast of Oklahoma City

and you find yourself

standing in the middle of

what made America great in

the first place; The small

business entrepreneur who

is showing up the big guys

by doing more with less.

By combining common sense

with elbow grease and

applying high tech where

it does the most good,

they are forging

themselves into the type

of company that is bound

to survive the 90's while

many larger, better funded

companies may not. They

are a small specialty

house that produces not

only the newest, hottest

aerobatic monoplane in the

business, but have

developed a composite

capability that is

increasingly being called

on by aerospace

corporations to do the

prototype work they can't

do themselves

economically.

Bill

Zivko is an excellent

study in how sport

aviation technical

fall-out is reaching past

EAA-oriented markets to

effect other parts of the

economy, as well.

Bill is

often mistaken as being

extremely quite. Maybe

even a little shy. But

what people don't realize

is that he isn't just

being quiet. He is

listening. He is soaking

up what's around him and

learning. If he has one

characteristic, that's

probably the dominate one.

He always appears to be

learning.

Some

time in the late 1960's

Bill decided working for a

Wisconsin FBO wasn't

taking him where he wanted

to go. An AI, he didn't

want to look down the road

at his future and see an

endless string of annual

inspections with an

occasional radio

installation here and

there. He wanted something

with more excitement and

colour.

He

found it in Newton, Kansas

with a guy named Jim Bede.

At that time Bede was up

to his neck in the famous

BD-5 project and Zivko

lent his talented hand in

building up the mini-jets.

The BD-5J. Since that day

Zivko has never completely

gotten away from the

little jets. He worked

with Bobby Bishop for

years maintaining his

airshow 5J and today still

works with Leo

Loudenslager on the Bud

Lite Airforce's little

kero-burner.

Bill

wound up back in Wisconsin

after the demise of the

Bede project, but several

years later received a

phone call from another

Bede alumnus, Burt Rutan,

who asked Zivko to come

work with him at Scaled

Composites. They were just

building up a head of

steam to begin the Beech

Starship project and Rutan

needed people who knew how

to get things done in a

shop environment. Bill

moved his family to the

high desert of Mojave and

he became shop manager for

Scaled Composites. If he

was looking for exciting

projects, he was certainly

in the right place.

Although Zivko's primary

background had originally

been in traditional

aircraft materials, he was

little by little moving

deeper into the

composites. By the time he

left Scaled Composites in

the mid 1980's he

recognized the advantages

of the materials and

continued working with

them in his own business.

Bill

and Judy spent a number of

years in the Oklahoma City

area before deciding to

relocate their shop into a

brand new

hangar/shop/office complex

on the Guthrie airport. At

that stage of the game

they were already going in

two directions at once,

one of which came about

from their friendship with

the late Tom Jones, a well

known aerobatic competitor

and airshow pilot. It was

through Jones they were

exposed to the ever

changing arena of

unlimited aerobatic

competition.

The

high-G world of unlimited

aerobatics was proving too

much for the Stephens/Lazer

type monoplane wings. Even

though the wood wings used

railroad-tie spars, they

were delaminating and

actually breaking. Even

with all the mods worked

into the wings by pilots

such as Leo Loudenslager,

the wing was still too

marginal. It was a safety

item they all worried

about.

Besides

being a safety item,

getting wood of high

enough quality and long

enough to make the 24 foot

spar wasn't easy and was

becoming increasingly

expensive.

Zivko

looked at the wing and

immediately saw an

application for

composites. He knew he

could build a stronger,

lighter wing and at the

same time update the

aerodynamics. The reason

he had such confidence in

himself was he had a cadre

of friends, courtesy of

his time with Scaled

Composites and other

similar projects, who were

at the forefront of

composites design and

engineering.

Using

input from pilots like

Jones and Loudenslager,

Zivko made up a list of

factors that had to be

primary design parameters.

Those at the top included

high roll rate, low stall

speed and extremely high

strength. Bill knew pilots

were pilots. They didn't

want to worry about all

that mechanical stuff.

They wanted to pull and

not worry about it. Since

10 G's wasn't unusual in

an unlimited sequence,

Bill decided his Lazer

replacement wing would

have a safety factor of

two, giving the wing a 20

G ultimate. At that number

he felt safe.

The

final design combined some

of the industry's best.

John Roncz designed a new

airfoil that would have a

low stall speed, would

corner well and have

predictable, well-behaved

characteristics at both

ends of the envelope. The

preliminary wing layout

was done by Paul Finn,

while Dave Boldenow, a

Boeing composite engineer,

did the structures. When

the prototype popped out

of the oven, Zivko loaded

it to 20 g's and found a

deflection of only a

little over four inches.

Now that's stiff!

The

production wing weights

224 pounds and is good for

20 Gs, versus the old

wooden 12 G wing that

usually weights around 250

pounds.

The

wing was first installed

on Joe Olson's Lazer with

many more following right

on the heels of that one.

Zivko Aeronautic's wing,

the Edge ZA-1 is earning a

reputation for giving the

Lazer a new lease on life.

In fact, Livko even began

custom building airframe

components for customers

who wanted their own

airplane that incorporated

the wing along with a

bunch of other

modifications engineered

by Zivko. They call their

four-cylinder airplane the

Edge 360.

Bill

and Judy looked at the

track record being

established by their wing

and decided the next

obvious move was to build

their own high performance

airplane around that wing.

They wanted an airplane

that could successfully

bump heads with Sukhois

and Extras. That meant

going to a six cylinder,

I0-540 in place of the

Lazer's 0-360. There are

lots of places in

everyone's mechanical life

where the only logical

solution for a situation

is a healthy dose of cubic

inches. Or a bigger

hammer.

By the

time Zivko Aeronautics was

getting ready to start

into their own airplane

project, they were already

a production shop which

had a client list

including names like

Tinker Air Force base, Leo

Loudenslager and a most

interesting client named

Aurora Flight Sciences.

Aurora's products were

ultra-high altitude,

unmanned aircraft which

were aimed at doing all

sorts of environmental

surveying up where manned

aircraft were nearly

useless. These aircraft

were designed to work

between 80,000 and 100,000

feet while carrying

payloads that sniffed the

atmosphere for bad stuff

or could loiter on top a

hurricane for most of its

life cycle. They measure

their loiter times in

days, not hours! The

current production

aircraft, the Perseus B

has a loiter time that can

be extended up to four

complete days. They can do

global-scale chemistry

surveys over nearly half

the earth's circumference

in one flight.

Obviously these airplanes

are special purpose and

rely on light weight and

long wings to do their

thing. And that's where

Zivko Aeronautics comes

into the picture. The huge

(59 foot) wings wouldn't

be possible without

composites and Zivko built

not only the wings, but

all composite components

including the tail and

fuselage as well.

There

are a lot of composite

fabrication companies in

the world that could build

the components, so it says

something that Zivko

aced-out many much larger

companies.

With

their moves into the big

time world of composite

engineering, a full-time

engineer, Todd Morse (his

great grandfather invented

the code), was added to

the staff along with

complete CADCAM

capabilities. All of this

experience and

capabilities were brought

to bear on their unlimited

bird, the EDGE 540.

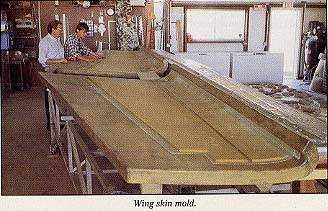

The

heart of any aerobatic

airplane is the wing,

which in this case is

probably one of the most

carefully designed and

manufactured wings in the

country. Zivko prides

itself in quality control

and details. They go so

far as using raw materials

that each carry their own

verified certifications

which are kept on file for

each component made. Each

lay-up has its own sign-up

sheet so it can be

verified later that it was

laid-up at a given angle,

done by a specific

individual and signed off

as being correct by an

inspector. Every single

step from the

manufacturing of the raw

materials to the final

paint coat is carefully

documented and inspected.

The

skin itself is glass with

a foam core stabilizing

the skin. The ribs are

Nomex filled, carbon fibre

layups and the spars are

mostly carbon fibre. The

layups are done in a clean

room that doubles as a

paint booth and curing is

done in Zivko's own 26

foot long oven.

The

fuselage is relatively

traditional, having

evolved from the Lazer

with careful attention

paid to those areas where

several decades of

competition have revealed

weak points. This is

another area in which

Zivko took advantage of

those experts who know

what works and what

doesn't. They carefully

documented the histories

of performers and

competitors who are flying

similar types of tubing

structures and noted where

they were having problems.

Then they sat down with

their own computers and

proceeded to design an

entirely new fuselage

which hopefully eliminated

all those problems.

Although the fuselage

looks to be a Lazer

derivative, it is actually

a completely new, computer

designed structure.

Next in

their development program

will be replacing the

wire-braced empennage with

a completely composite

unit.

Weight,

weight and weight are the

first three factors

constantly nagging at the

mind of any aerobatic

designer. Lowering the

weight is the same as

gaining free horsepower

and in competition, every

ounce counts. In the case

of the Edge 540, the quest

for ever-lower weight

brought composites into

play in many areas other

than primary structures.

Practically every external

fairing which would

normally be made of

aluminium is carbon fibre.

This includes the turtle

deck, canopy frame and

even the instrument panel.

The cowling, complete with

nose bowl and all

fasteners barely weights

12 pounds which shows the

concept does work.

The

super slick and tight

fitting canopy frame

doesn't have a bolt or

screw showing because the

canopy, as well as all

Plexiglas panels, is all

bonded in place rather

than being bolted. This

makes for light, rigid

installations that can be

replaced by simply sanding

the back of the mounting

flange away and bonding in

a new piece.

The

engine in the EDGE 540 we

flew was powered by a

mildly tuned Monte

Barrett, parallel valve

IO-540 pushing about 310

hp (dyno verified) into

the air via an MT

three-blade. In the Edge

540 kits or finished

aircraft, the propeller of

choice would be a

three-blade, composite

Hartzell.

The net

result of all their

attention to detail is an

unlimited aerobatic

airplane with a 20 G wing

that, in the case of the

example we flew, barely

weights 1170 pounds. With

a normal aerobatic weight

of 1527 pounds, that puts

the power loading at under

5 lbs/hp. No wonder it is

such a rocketship!

The

price of a complete kit,

minus the usual engine and

all other kit stuff that

isn't usually included, is

$57,052, which includes

every single option

including having the wing

pre-mounted to the

fuselage and all tubing

finished, painted and

pre-oiled. This also

includes the wing tank

option that gives an

additional 33 gallons over

the 19 gallons in the

fuselage tank. Zivko

stresses that even though

they've done much of the

work there is still a fair

amount of work to be done

by a builder. They view

their kit as being half

way between a plans-built

airplane and a true,

ready-to-assemble kit.

Incidentally, of the total

price, $18,995 is for the

basic wing which can also

be fitted to your old

Lazer fuselage, should you

have an extra one laying

around.

Mark

Pfiefler, an airshow

performer and professional

pilot from the Oklahoma

City area not only loaned

us his airplane for the

pilot report, but did the

flying during the photo

session. He showed a

tremendous amount of

patience and self control

in hiding his apprehension

at having someone else fly

his "baby", although those

watching during the flight

said he was pacing the

ramp like an expectant

father. Can't say as we

blame him.

A

walk-around on the

airplane shows the

standard stuff expected of

an unlimited airplane

except you seldom see it

done this well. The gaps

at the back of the canopy

combing, for instance,

couldn't have been .025"

and were absolutely even

from one end to the other.

Ditto the cowling or

anywhere else anything

came together. The turtle

deck combing flowed down

around the vertical fin

and was finished with a

neatly detailed little

window that put the

elevator horn in full view

for pre-flighting. A nice

touch!

Saddling up, it became

immediately obvious Mark

had the cockpit tailored

just for him and he is

mostly legs. Long ones!

Bill Zivko had to get in

there with one of his guys

and adjust the rudder

pedals back so I could

come even close to getting

full rudder.

Locking

the canopy down, I cranked

the engine, paying

particular attention to

Mark's directions for a

hot start. The big

Lycoming caught on the

third time around and

showed no indication of

stumbling when the mixture

went in.

The

Haig locking tailwheel was

controlled by a plastic

coated cable stretched

back from the vertical

piece of tubing just under

the throttle. Hook a

finger around the cable

and pull and the tailwheel

was full swivelling. Leave

the cable alone and the

wheel was locked straight

forward. It was a nice,

fool proof arrangement,

although I still prefer

steerable tailwheels.

As I

lined up on the runway

centreline, I was pleased

to see I could see. Unless

you've flown some of the

mid-wing monoplanes with

the low canopies you don't

realize how blind the

pilot is. The wing usually

covers most of the

pavement. The Zivko 540 is

a long ways from being a

C-172 in the visibility

department, but it's not

nearly as blind as some of

the other unlimited. I had

enough of the 75 foot wide

Guthrie runway in sight I

relaxed. Until that point

I had been really worried

about the landing. Now I

was only apprehensive.

The

takeoff wasn't so much a

takeoff as it was a cat

shot off a concrete deck.

One second I was beginning

to move the throttle and

the next I was clocking

100 knots and going up at

an angle that has to be

seen to be believed.

Everything about the

experience was immediate.

The engine spooled up the

instant the throttle moved

and the airplane reacted

just as instantaneously.

Left hand moving forward,

airplane moving easily

twice that fast, runway

flashing past, brain

telling my right hand to

be gentle in bringing the

tail up and the long hand

on the altimeter started

flashing in a circle.

By the

time we were off the

ground and I glanced

inside, the airspeed was

blasting past 110 knots

and it was all I could do

to keep it down to 120.

Actually, I was well out

of the pattern before I

realized the airspeed was

in knots, not mph,

otherwise I would have

pulled the nose into an

even more ridiculously

steep attitude to keep it

down. As it was, I timed

the rate of descent at

something over 3,500 fpm.

Now that calls for

exclamation marks!

The

instant the gear left the

ground I could feel the

ailerons in my hand. I

don't mean I could feel

the airplane moving, I

mean I felt the ailerons,

as if their trailing edges

were nested in my palm and

I could sense their

tiniest movement and the

airplane instantly

reacted. This is not an

airplane for those of

heavy hand. But, even at

that early stage I could

tell the stick ratio was

long enough the airplane

didn't feel twitchy.

As

quickly as the airplane

responds to a control

input of any kind it would

have been easy for the

airplane to have been like

trying to balance on a

bongo board (those things

where you try to stand on

a board balanced on a

roller). The stick ratios

eliminate that feeling

almost completely. Al

though the perceived

pressures might as well be

zero, they are so light,

the stick has to move far

enough that the pilot has

total control and is able

to really fine tune his

movements.

It also

didn't have any breakout

forces to speak of, in any

direction. In fact, a

minute or so later when

levelling out at 4,000

feet, I was treated to a

unique control feel. It

was unique because all

stick force gradients were

perfectly flat. Perfectly

flat. The forces in any

direction didn't seem to

change at all regardless

of how far I displaced the

stick. In pulling "G", the

stick force felt the same

all the way through. The

pressure at full aileron

deflection was the same as

barely starting a turn.

The pressures also didn't

change with speed.

It was

hard to get full aileron

deflection because the

airplane whipped around so

fast, that by the time you

could get the stick up

against a knee the

airplane would already be

right side up. The roll

rate has been timed at 420

degrees, which is enough

to blur the horizon. This

is especially true in

doing vertical rolls. I've

never been especially good

in the vertical, but it

goes around so fast you're

into the second one before

you know you've come close

to finishing the first

one.

Does it

stop while rolling? On my

first vertical I thought

I'd do a quick half roll

to see how it felt. Blur!

Twitch the stick back the

other way to stop and my

head bumped the side of

the canopy as the airplane

slammed to a halt. Crisp

is hardly the word for it!

A lot

of airplanes that have

light control pressures in

pitch will be asymmetric

in their behaviour.

They'll be light when

positive but it takes a

healthy arm to get much

negative G on the

airplane. This is

absolutely not the case

with the Edge, it comes as

close to being the same

outside as inside as any

I've seen. It takes a

little more arm, but only

a little and just a touch

of trim lets it fly hands

off inverted. This made

manoeuvres like rolling

360's a whole lot less

work.

The way

the airplane handled when

slow is at least as

impressive as how it

handled the fast stuff.

Pulling out of the tops of

verticals, I was being

ginger, just letting it

zero G its way over. The

big engine let me do

anything at that point

because I was purely

ballistic, just a

passenger behind a

whirling MT. At one point

I bought the power back

while pulling over the top

at zero speed waiting to

see what it would do. It

didn't do anything. It

kept on pulling. At least

twice I found myself

messing around at speeds

around 30 mph, full back

stick and still flying

around the corner because

I was low on G. Then I got

down just over stall and

honked into a hard corner

trying to stall it. It

would buffet a little but

not do anything unusual.

Then I'd unload, hit the

power and go shooting

straight ahead like out of

a sling shot. Coming out

of a slow speed situation,

it acts as if it has JATO

bottles.

Incidentally, a couple of

times I played with the

power while going vertical

down hill to see what the

prop would do. I pulled

the power all the way back

and even though I was

pointed straight down, the

prop would flatten out,

airplane would slow down

and I'd slide forward into

the straps. Later, while

shooting landings, I got a

kick out of the way the

big prop acted like a

spoiler. Just a touch of

power would keep the

blades from flattening

out, but pull the power

and it acted like drag

chute.

The

first flight of any

airplane is a tentative

meeting of friends, you

circle around one another

trying to figure out the

best approach. That's why

a second meeting is always

a must. You've had time to

think about the first

meeting and you've got all

sorts of ideas about the

second. Unfortunately, I

only had time for one

flight in the EDGE 540

which is no way to judge

an unlimited aerobatic

airplane. Assuming, that

is, I was capable of

judging it in the first

place, which I'm not. I

doubt if there are 25

pilots in the entire world

capable of truly saying

how well the airplane

stacks up against the

unlimited hot dogs and I'm

not one of them.

Judging

from the tapes I've seen

of Kirby Chambless flying

his Edge 540 at Fond du

Lac, there seems to be

little doubt the airplane

can do some amazing stuff,

including hovering at zero

airspeed.

It

would be nice to see

something like the Edge

make a serious mark for

itself. It's American born

and bred and comes out of

a small shop tended to by

loving hands. In a wildly

three-dimensional sort of

way, the Edge 540 and

Zivko Aeronautics

represent the best of the

American spirit. Get an

idea and make it happen!

And that's exactly what

the Zivkos are doing.