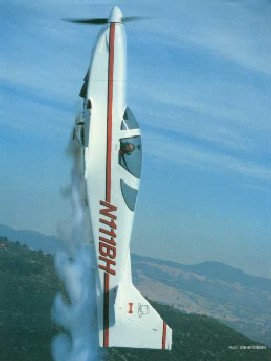

Glasair 3

by Budd Davisson, courtesy of

www.airbum.com

Looking

over the long snoot of the

Glasair III, my throttle

hand wasn't even halfway

to the panel before I knew

I was in serious emotional

trouble. Once again, I

felt my heart slipping

away as fast as the Speedy

G-III was sucking he

runway under us. Before I

even had the nosewheel of

the ground, I knew that

this was the start of a

too-familiar, frustrating

relationship-I was falling

in love with something I

couldn't have. One

comforting thought came to

mind: I could at least

have a one-night (or a

one-afternoon) stand with

this stunning beauty.

The reason

I felt my emotions being

taken from me at such an

early stage in my

relationship with the

G-III was because

everthing felt just right,

and seldom does this

impression lead to an

emotional over-reaction, a

fact which would be

confirmed during the next

several hours.

We had

lined up on the runway at

Oshkosh, watching a Breezy

float its way off the

ground ahead of us and

seeing it turn right in

the prescribed manner so

as to avoid over-flying

the east/west runway.

Since our stall speed

probably approached the

Breezy's red-line, we

waited, and we waited some

more, until the FAA flag

man refused to let us

occupy the middle of the

pavement any longer, and

frantically waved us down

the runway.

The

throttle started in, then

the runway started moving.

Suddenly, in a nanosecond

or thrice, the runway was

blurring, and I tightened

my grip on the stick,

gently urging it back.

Obediently, the nose

pivoted up, covering the

sky ahead, while the mains

remained hesitantly on the

ground. Then, before I

knew it, the

airplane was off the

ground. I quickly slapped

the gear switch up, my

eyes riveted on the Breezy

which was wafting its way

up crosswind.

The Breezy

had turned. so wide that

there was only a few

hundred yards left for us

between it and the

forbidden zone. In the

interest of keeping the

pucker factor within

reasonable limits, I

brought the power back to

24 square and pushed the

nose down, keeping the

Breezy in sight at all

times. As we zipped past

the bug-spattered Breezy

pilot, I rolled out of the

bank and headed for the

lake, glancing at the

gauges as I did. I looked

back quickly, even twice,

to make sure I was reading

them right. To my

surprise, even at that

power setting and a slight

nose-up attitude, I was

indicating 165 mph and

1500 fpm up. Talk about

rocking and rolling!

Yessir,

we're talking about a real

love affair with an

airplane here!

The Glasair III is what

happens when something

unbelievably slick hits

the homebuilt market with

something other than the

largest engine available

in it; it's generally only

a matter of time before

someone stuffs said

humongous motor under its

hood.

However, in the case of

the Glasair III, the

factory, Stoddard

Hamilton, beat the

homebuilders to it. Almost

before the first Glasair

II RGs started hitting the

streets as completed kits,

the guys up in Arlington,

Washington already had the

III in the moulds.

It would be easy to say

that the III is a hot-rodded

II - which it is - but as

is always the case, when

something is radically

hopped up, many more

features about it change,

than stay the same. For

instance, the wing area of

the two is identical (81.3

sq. ft.), as is the

wingspan (23.3 ft.), which

would lead one to believe

that it's the same wing,

but that's definitely not

the case. With a gross

weight of 2400 pounds

versus 1800 pounds, a red

line of 335 mph

(that's no typo), as

opposed to 260 mph, and -6

and -4 Gs (limit load),

you just know it would be

safe to bet that there

aren't many

interchangeable wing

pieces.

From the outside, the most

noticeable difference is

the extra 2.5 feet

of fuselage length, part

of which is in front of

the wing, and part

aft of it. It stretches

the airframe out to where

the boxy look of the II

has been converted into

nothing short of perfect.

The interesting thing

about the Glasair Ill is

that, although it's been

only a little over two

years since it was first

introduced, there already

are a number of kit-built

planes in the air. That

says several fairly

significant things. First,

it says that there are a

lot of guys out there with

plenty of bucks, since it

would be tough to do a

GIII for less than $60,000

(and $85,000 is a

lot closer) {editor's

note from the year 2000.

Make that $100,000, plus

the factory has in the

process of changing hands

after going Tango Uniform).

Second, those same guys

with the money have

excellent taste. Third,

the airplane goes together

exactly as advertised.

Ten years ago, this

airplane would have been a

radical breakthrough both

in performance and in

structure. Today, however,

the entire homebuilding

market has become blaze'

on both

scores.--especially in the

area of structure.

Hamilton-Stoddard was the

first company to use the

moulded composite concept

for a homebuilt kit with

the original Glasair I.

Rutan's method was to

build the airplane around

foam cores, laying the

glass up on the outside.

Hamilton-Stoddard hit it

the other way around, and

the skin and most

structural parts are

glass-foam-glass

sandwiches which are laid

up in female moulds. This

means that the parts

supplied are similar to

those of a plastic model

airplane kit in which

major pieces of structure

are bonded together to

form completed components.

The wing of the Glasair

series, for instance,

comes with the spar

already pre-moulded into

the bottom skin, just

waiting for the rest of

the ribs and the top skin.

This type of structure

progresses incredibly

fast. But it also means

major (as in really big)

investments in hard

tooling at the factory

which, in turn, translates

to increased kit cost to

the buyer. In the case of

the G-III, that means

$3350 (or

approximately ten percent)

up front.

Glasair

uses the vinylester epoxy

system, as opposed to the

polyester system favoured

by Lancair. There is a

raging battle going on

between the users of the

various systems concerning

the effects of skin

temperature on the

material, especially at

the joints where the

builder-applied epoxy

isn't oven-cured. Rutan is

on the side of the

vinylester,

always-paint-it-white

crowd.

Somehow, as

we were blasting past that

Breezy, at Oshkosh, none

of the background

information about the

airplane was on my mind.

All I could think about

was, er, was - actually, I

wasn't thinking about

anything at all was just

sitting there, soaking in

the entire experience. We

wanted to get into some

clean airspace so we could

fool around, but first we

had to thread our way

through the mess of

airplanes which were

inbound to the airport. So

we kept it low and slow

(180 mph!) until we were

ten miles out, at which

time I squeezed on 25

square and pointed it

up, watching the VSI work

its way around to a solid

3100 fpm and I was still

at 170 mph! This Glasair

III has got to be the

performingest civilian

machine ever built. In

actual fact, in most

departments, it could run

away and hide from all of

the Warbirds, with the

exception of the Bearcat,

which is the only US

fighter capable of

out-climbing it.

The most

magical thing about all of

this performance is that

it's so easy to manage.

While the control

pressures are reasonably

light, the response is

instantaneous, and seems

perfectly proportional.

Want a little roll? Use a

little stick. Want a lot

of roll? Use a lot, etc.

And I wanted as much roll

as I could get. So, no

sooner had I put the nose

on the horizon at 6500

feet, then I yanked it up

into a series of aileron

rolls, and then slow

rolls. Then whatever

fractions of them I wanted

to make; four points,

eight points, the G-III

did them as if it had been

digitally controlled by

computer. The only problem

I had with those

manoeuvres was keeping the

airplane from gaining

altitude.

The most

mind-blowing point in the

flight (actually, there

were quite a few) was when

I flopped the G-III over

on its back and

cross-checked the

altimeter with the nose so

as to know where the level

inverted flight was. I was

pulling about 23 inches,

which translated to about

65 percent. While

hanging upside down, I

glanced at the airspeed

and couldn't believe where

the needle was pointing:

it was happily nailed to

the narrow space between

235 and 240 mph, at

6500 feet and little

more than 23 inches.

Later I put the

appropriate temperatures

and other stuff into the

little calculator and it

came out to 263 mph true.

Stoddard-Hamilton

literature says 269 mph

with those power settings,

so it is probably

absolutely correct since I

was only approximating the

manifold pressure.

As I

dropped the nose inverted,

then rolled out, the speed

went past 250 indicated.

Increasing the "G" to

about four in the pull, I

glanced out at both wings

and did a really poor

imitation of a vertical

roll. I was off in every

direction, but the

airplane kept going uphill

anyway. I pulled over the

top, handed the controls

over to Bob Herendeen in

the other seat, and he

sucked it up into a

vertical with a noticeably

crisp halt before

hammerheading out. Nice,

really, nice!

Bringing

the power back to idle, I

pulled the nose up and

waited until it slowed,

which happened much more

quickly than I had

expected because I'd

forgotten what a

marvellous speed brake a

gigantic propeller makes.

I held it there until the

speed worked its way down

to 80 mph and then a

buffet set in before it

broke gently at about 77

mph indicated. However,

the break was nothing

unusual and the instant

the elevator was released,

or the power applied, the

airplane was flying again.

In a dirty configuration,

only the break became

sharper.

During the

few times we weren't going

either up or down, or

around and around, I found

I could let the G-III take

care of itself without

worrying that it would do

anything out of the

ordinary. Its stability in

roll is quite a bit closer

to neutral than on any of

the other axis. In both

pitch and yaw, the

airplane heads back

towards straight and level

immediately, almost no

matter what you do with

it. In pitch, it would

take two cycles to go

level and in yaw, only one

cycle was needed.

We headed a

few miles south of

Oshkosh, into Fond du Lac,

to shoot some landings,

and I should probably

mention that the flight

wasn't without a few

nervous thoughts on my

part. I always have a

terrible time slowing down

high-performance airplanes

without hanging some "G"

on them. However, with the

G-III, all it took was

bringing the power back;

that fat prop took

care of the rest. The

airplane decelerates at

least as easily as a

Bonanza, and much easier

than a Mooney.

On

downwind, we got the gear

and half flaps, and I made

a wild guess as to how far

out I should go before

turning base. I kept it a

little tighter than usual,

figuring that the III

would settle quickly, but

I was wrong, and I came

very close to being too

high. Fortunately, this is

one of those airplanes

which has so much drag,

when everything is hanging

out, that I could drop the

nose and shed 100 feet

without gaining much

speed. We used about 105

mph on downwind, and bled

that off to 95 mph

on short final.

I hadn't

noticed that I was sitting

a little low in the

airplane until it came

time to break the glide,

and I realized that I was

looking through the very

bottom of the windscreen

where it's slightly

distorted. So, on my first

landing with the G-III, I

was a bit higher than I

should have been. Still,

the airplane mushed

through the last couple

feet in ground effect, and

gave me quite an

acceptable landing. The

next time around, though,

I had a much better idea

of where I was, and the

airplane landed as easily

as any Bonanza.

All in all,

I was amazed at the wide

envelope of the Glasair

III and the fact that it

required practically no

talent to fly it

adequately. I'm no

hot-shot, high-performance

pilot, but the airplane

seemed very comfortable to

fly from the very

beginning. I'd say that

almost anybody who can

handle a Mooney or Bonanza

(which is just about

everybody) would find the

G-III an easy airplane

into which to transition.

The only thing which might

surprise a pilot who flies

this Glasair for the first

time is the way it blasts

down the runway on take

off absolutely amazing. It

is, however, a highly wing

loaded airplane and asks

that you remember that at

all times, when you're in

the pattern. It's

essential that you fly the

right numbers on final, as

it is probably very

unforgiving of getting it

low and slow. VERY

unforgiving.

The G-III is one of the

very finest of the Hot

Homebuilt breed. It's an

incredible combination of

raw, brute performance and

mild, well-developed

manners. This airplane has

set a standard for

utility, performance and

out-and-out fun which will

be hard for any other

design to match.

|