The L-5 evolved when

someone from the military approached the

Stinson Division of Vultee Aircraft and said

"Build me an airplane that lets me land

short. And make the plane so I can really

see out of the cockpit. And the aircraft has

to be as functional as a jeep. And oh yeah,

while you're doing this, to make sure the

concept really works, make it ugly!"

(Actually, the military asked for a

modification of an existing airplane, but

Stinson said they could build a better one

from scratch, and they did.)

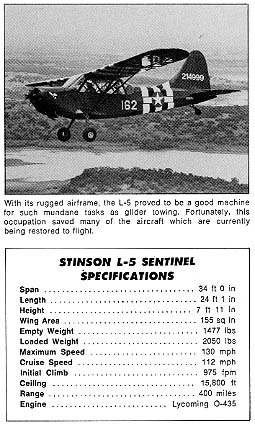

Ugly, obviously, is a

subjective term but, in the case of the

faithful old L-5 Sentinel, it has to be

applied only to aesthetics since, when trees

loom large in the windshield, the L-5 is

truly a beautiful airplane in which to be

aviating. A lot of adjectives can be used to

describe a Stinson L-5, but "petite" isn't

one of them. In fact there is nothing about

the airplane that even comes close to being

dainty. Where the L-5's peer group of Piper

and Taylorcraft putt-putts derived all of

their STOL performance (such as it was) from

65 horsepower and lightweight, the L-5 got

its reputation from pure brute force and

tank-like strength. Its broad snout covers a

six cylinder 0-435-1 Lycoming engine pumping

out 190 Clydesdales. That powerplant is

bolted to a fuselage tubing structure that

looks like it was laid out and executed by a

vocational agriculture trade school, using

tubing twice the size of that in any other

L-Bird, and it is all arc-welded together

with farm machinery techniques. Keeping all

that bulk off the ground are two gear legs

as big around as the average Green Bay

Packer's forearm, and each of these gear

legs is given a least a foot of vertical

travel to transmit big bumps to the inboard

shock struts.

It only takes a minimum

of investigating and common sense to know

the L-5 is the airplane to be flying when

you find you have to go through the trees

and not over them.

From a prospective

buyer's point of view, the wings and tail of

the L-5 are by far the most critical

components since they are made out of wood,

and were part of a wartime philosophy in

which machines such as the L-5 were

considered expendable. Nobody thought these

wooden structures would still be flying over

forty years after the fact, so they have to

be inspected closely.

THE WINGS USE A TYPE OF

STRUCTURE THAT IS almost unique to the L-5

in that they are fabric-covered rib and spar

affairs, but they have none of the usual

drag anti-drag wires. Instead, these forces

are taken out by plywood shear panels which

cover the entire bottom of the wings. This

imparts great strength and weight to the

wings, however, the drain holes at the back

of each rib bay absolutely must be clean or

a huge amount of water is trapped which

eventually can rot all the wood within

reach. The same keep-the-drain-holes-clean

philosophy applies to the tail. The entire

empennage is of plywood monocoque

construction with no brace wires so any

amount of rot or fungus could help your wife

collect on your insurance policy.

If there is one

under-designed portion of the airplane, it

is the brake system. True to late

1930s/1940s design concepts; the brakes are

the old fashion bladder type, ie: a

flattened rubber bagel snuggles inside the

brake drums with blocks around the outer

circumference. As you pump fluid (it must be

mineral oil) into the bladder, it expands

and forces the blocks against the brake drum

which is supposed to stop the airplane. This

is not always the case. When using freshly

rust-free, turned drums with the rest of the

system up to par, the brakes are adequate.

However, as soon as you go up in tire size

the brakes become increasingly marginal

until, when you go out bush-busting with the

10 x 6 tires, your expander tube brakes have

all they can do to hold in place during the

mag check. That is one reason you see so

many of the airplane now fitted with

Cleveland disc conversions.

It

makes almost no difference what your

experience is in aviation or what you are

currently flying, you can be guaranteed of

getting a real charge out of saddling up an

L-5. It is a fun airplane in every possible

sense. In the first place when climbing

aboard, you actually do "climb aboard." You

scramble up the gear leg and the strut,

grabbing a hold of fistfuls of steel tubing

to hoist your butt up into the formed

plywood seat (non-critical materials,

remember?). Once on board you are sitting

really high in what has to be one of the

most starkly finished cockpits you'll ever

encounter. "Military Crude" is probably the

best way to describe the furnishings.

Everything in front and behind you is a maze

of tubing, giving the impression of being

stuck in a chromate green jungle gym. One of

the reasons for noticing the tubing is

because, from the waist up, the airplane is

entirely plexiglass-so the cockpit is

constantly bathed in sunlight and tubing

shadows.

It

makes almost no difference what your

experience is in aviation or what you are

currently flying, you can be guaranteed of

getting a real charge out of saddling up an

L-5. It is a fun airplane in every possible

sense. In the first place when climbing

aboard, you actually do "climb aboard." You

scramble up the gear leg and the strut,

grabbing a hold of fistfuls of steel tubing

to hoist your butt up into the formed

plywood seat (non-critical materials,

remember?). Once on board you are sitting

really high in what has to be one of the

most starkly finished cockpits you'll ever

encounter. "Military Crude" is probably the

best way to describe the furnishings.

Everything in front and behind you is a maze

of tubing, giving the impression of being

stuck in a chromate green jungle gym. One of

the reasons for noticing the tubing is

because, from the waist up, the airplane is

entirely plexiglass-so the cockpit is

constantly bathed in sunlight and tubing

shadows.

Under your left elbow, a

flap handle that would do justice to a

wheelbarrow juts forward-challenging the

pilot to give it a hefty heave, engaging one

of the notches in the vertical gate in which

it rides. The stick is even bigger than the

flap handle and boot-size rudder pedals are

on the far end of aluminium clad wooden

trays. If the airplane is correctly

restored, an archaic-looking carbon pile

regulator should be occupying all the space

between your feet while your head would be

framed by variations of old black boxes that

held tube and crystal radio sets.

In the late models-the E

and G ambulance version - a crank hangs out

of the overhead directly in front of the

pilot's forehead which, when turned, will

droop the ailerons 15 degrees to make them

into "flaperons" for full span additional

lift in high pucker factor situations. The

ambulance models also have one of the more

hysterical military placards you'll run

across. It states, "Intentional spinning

with litter patients is prohibited." Makes

you wonder what ambulance pilots had been

doing to fight boredom when returning with a

casualty, doesn't it?

O-435 Lycomings are not

known for a mellow exhaust tone. They have a

very distinct tractor sound that fits very

well with the airplane's funky ambiance. You

don't notice the noise on first flight,

because you're preoccupied watching the way

all the glass panels are dancing in unison

to the engine rpm. Most of the rattling and

clattering is a function of propeller

balance. If the airplane has been parked for

any length of time with the prop in the

vertical position, one blade will pick up

water and treat you to a vibrating massage

every time you crank it up. We once ferried

an L-5 that had sat dormant for a few years

and the prop was so far out of balance, the

old B-16 compass on top the instrument

looked like it was full of root beer foam.

When taxiing out, the

high seating position, the jungle gym effect

and all the goings on occasioned by the

Lycoming melt together to give the feeling

you're truly flying a Warbird since there is

absolutely nothing even vague civilian about

this machine. At this point, the L-5 rates

right up there with the Mustangs and Texans

in terms of impact but you are getting a

much bigger bang for the buck-if only

because the bucks are much smaller!

Takeoff is simply a

matter of poking the tractor in the rear and

waiting. Even though the L-5 has plenty of

ponies up front, it's dragging along a

pretty good-size carcass so the plane isn't

going to leap forward. The Lycoming

generates so much wind that you can hoist

the tail in the air almost instantaneously

and, if any flaps are down, you'll be off

the ground almost before you're ready. If a

no flap takeoff is elected, with the tail

hoisted up past level you'll find she'll run

on the mains until ready for a lunch break.

Put her in a slightly tail down position and

she'll growl down the center line until a

suitable speed is found and you're up and

flying. During the takeoff a minimum amount

of attention is required with your feet

unless there is a crosswind, at which point

that tiny rudder will be used to try to make

up for all that side area.

Don't expect the L-5 to

go clawing upstairs like an autogyro. Yes,

technically it is a STOL airplane, but you

have to apply a little common sense. Just

for the heck of it, why don't you give a

little bit of margin and not try to make

this forty-year-old go hopping high hurdles

right off the bat. Incidentally, one

variation of the climb-over-the-trees

routine is possible but not recommended with

the L-5. You can gently cross control,

forcing the plane to climb in a corkscrew

fashion, making believe you're climbing out

of a milk bottle.

If you didn't notice the

lack of control friction on the ground, you

certainly will in the air because the

Stinson L-5 has one of the very best sets of

controls of any airplane from that period.

In typical Stinson fashion, every single

bolt in the control system runs through a

bearing. Even the control stick has a

bearing stuffed into it which reduces system

friction to absolutely zero, totally out of

keeping with airplane's appearance. You'd

expect something a little heavy, a little

crude, a little scratchy, but that is

definitely not the case.

Years ago we took

delivery of a rather bedraggled G-model

after buying it from the Civil Air Patrol on

a sealed bid ($1777.77!). The CAP was

getting rid of the L-5 because they were

having handling difficulties on the pavement

with the big tires. I took the bird around

the patch to make sure everything worked and

was surprised at the controls. On down wind,

the controls felt so good I pulled the nose

up and did two aileron rolls. The colonel in

charge turned to my partner and said, "I've

always wanted to do that but never had the

guts." He should have done it.

In level flight the L-5

is a joy and then some. With the windows

folded down and the breeze whipping around

inside the airplane, you have an incredible

view of everything. Regardless of what

anybody says, there is something to be said

for sitting on top of the world in an

L-Bird. It is a feeling that doesn't exist

in every airplane. Even though the L-5 is

incredibly spartan in creature comforts, a

careful selection of cushions will make the

airplane as comfortable as any you've flown.

Be advised that a good intercom is essential

if you expect to talk to the passenger

because the noise level is very definitely

pre-OSHA and very World War Two authentic.

As a cross-country

machine, the L-5 is several giant notches

above other L-Birds for travelling (with the

possible exception of the L-19). Depending

on how well the airplane is rigged and

you're willingness to lie, the machine will

give you an honest 100-115 miles an hour.

The downside is you'll be burning in the

neighbourhood of 12 gallons an hour, give or

take a little.

The L-5 is fun no matter

what, but especially fun when you come into

land. This can depend on your definition of

"fun." Any airspeed number on final is

perfectly workable . . . if you are off the

ground and flying, you have enough speed in

the L-5. The manual does recommend flaps for

short field approaches. In reality, the L-5

isn't that fussy, but the slower you

approach, the higher the rate of sink and

more throttle will be needed to keep from

flopping on to the ground like a ton of

surplus tank treads. The wing slots give

plenty of aileron at all times so don't

worry about that aspect of slow air speed.

When the flaps and flaperons are out, a near

vertical final approach path can be assumed.

One of the nicest things about the aircraft

is that it can build up an incredible rate

of descent, and the pilot can wait until the

very last second to nail the throttle which

will break the rate of descent almost

instantly-allowing a less than

spine-crushing arrival. As soon as hitting

the ground, stand on the brakes almost as

hard as you like and turn the airplane

around to find only a few hundred feet of

runway have been used. Then you can send

your underwear to the laundry. This ability

to build up a very controllable high rate of

descent makes the airplane much more suited

to getting into short fields than even a

Super Cub, which just refuses to sink at a

high rate.

In more normal approaches

to a paved runway, it is worthwhile to pay

attention to the directional control. The

L-5 is not a difficult airplane to land, but

it doesn't have much going for it if you

lose control. The rudder is small and has a

difficult time overcoming all that vertical

fin area while the stock brakes on big

wheels will not straighten out a

well-developed ground loop. The tail wheel

assembly also needs some looking after to

make sure the unit is doing its share of

steering duties. If you go to sleep at the

switch, allowing the airplane to get away,

the best you can do is just take off at an

angle. If this happens, it's your own fault

since the airplane is doing everything so

slowly.

As a point of

information: The giant 10 x 6 tires look

great on L-5s and allow landings on anything

up to and including railroad tracks but, as

mentioned earlier, they do reduce braking

efficiency which is a minor problem compared

to what they do to landing gear geometry.

When the landing gear extends on takeoff,

the bottom edge of the 10 x 6 tire actually

swings in and is inside the pivot points of

the gear legs. If you make a grease job

touch down, it is quite possible for one

gear leg to go out and the other one pull

in. This creates spectacular ground handling

problems. When flying with the big tires it

is generally better to make a somewhat

sudden arrival, either a wheel landing or a

fairly firm three-point to make sure both

legs spread. As another point of

information, the 10 x 6 tires are reportedly

DC-3 tail wheel tires and they are darned

expensive.

L-birds in general have

become much more popular, a fact easily seen

at Oshkosh '86 where everything from L-2s to

L-19s seemed to be coming out of the

woodwork. Many pilots have discovered the

fun of military aviation isn't limited to

the big iron and big bucks. And they have

discovered the personality lurking behind

the curious looks of the lowly L-5. More and

more of the hulking Stinsons are being taken

out of their glider and tug roles to be

restored, refurbished, and refinished until

they are far superior to the planes which

hopped around the battle-fields of World War

Two. Accompanying its popularity, naturally

is the tremendous escalation in value. Today

it is not unusual to see L-5s in the $20 to

$30,000 bracket when only five years ago

they were a $4000 machine at the very

outside.

As Warbird projects go

there is probably no better value than the

L-5 . . . especially if you're willing to do

much of the work yourself. The supply of

spares is rapidly dwindling but it still

exceeds the demand in most areas. The

airplane requires the builder to check the

wood carefully but that is easily balanced

by the fact the 0-435 Lycoming is a nearly

useless engine since it was used in very few

airplanes, making the engine inexpensive to

buy. There is an STC for a constant speed

propeller but some of the STC parts, ie:

cooling eyebrows, are extremely hard to

find.

Of the various models of

L-5s available, the E and G ambulance

variants seem to be most numerous. It should

be pointed out that the back seats were

second-ary considerations since the

airplanes were primarily designed to carry

litter patients. The earlier models-the As,

Bs and Cs-were designed specifically to

allow observers to paste their noses against

the side window and report troop movements,

etc. Therefore it would seem logical that

those back seats would be much more

accommodating to the average size body.

That's up for verification since most of our

flight time is in G-models. With a G-model

you can forget about the cramped rear seat

and just lay down in the litter position.

Who knows. Put a reading lamp back there or

a portable TV and your wife might even like

it!

If you cut to the bottom

line what you have in the Stinson L-5 is an

incredibly fun-flying airplane that restores

like a really big Cub but has twice the fun

and twice the size for practically no

increase in purchase price. If you really

want to appreciate the airplane as a warbird

put its operating budget up against that of

a T-6 or a P-51 or B-25, or . . . you get

the idea. Go out and put your hands on an

L-5 and you'll find it to be one of the most

overlooked and underrated airplanes you'll

ever have a chance to strap on.