As I was strapping into

the airplane on

Scottsdale, Arizona's

ramp, I felt secure, if

nothing else because,

although the airplane had

only about 85 hours on it,

they had been at the hands

of over 75 different

pilots and almost all of

them had been hard

aerobatics. If it was

going to break, it would

have already broken.

Besides, the airplane had

just come out of Lewis

Shaw's shop being

completely inspected and

freshened up.

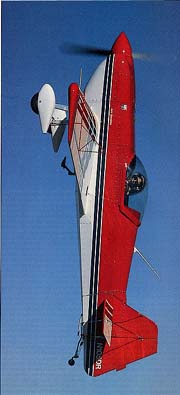

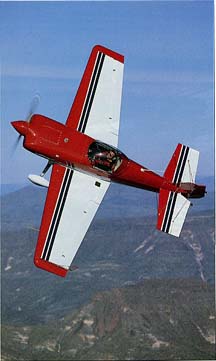

Everyone's first

impression of the airplane

is the same, "Boy, is that

thing small." It looked

miniscule out there on

that big Scottsdale ramp

and with only 19.5 foot of

wing (tips included) and

75.5 square feet of wing

area, it was small. A

single-hole Pitts thas

only a 17 foot span, but

98 square feet of wing

area, for comparison.

The

wing looks short because

it is so fat and it feels

like a gymnasium floor, it

is so solid, when stepping

up on it to board. Sliding

down in to the cockpit,

the wing tips seem to get

closer, but this is

feeling that disappears

almost as soon as the

engine cranks.

Chris

Gardner was sheparding the

airplane around for Lewis

and Dan, and he was a good

choice. Besides being a

mechanic, he personally

built the 0-320 Lycoming

that had been lifted right

out of a C-172. The engine

was essentially stock

except for an Airflow

Performance injection

system and slightly higher

compression pistons which

Chris feels makes it good

for about 160 hp. The prop

is a 74" diameter, 60"

pitch, metal Sensenich.

The

first impression on

boarding is that this

thing is really wide and

not just when compared to

a Pitts. I'm an FAA-standard

pilot in every dimension

and the longerons were at

least 2-3 inches outboard

of my shoulders, when

wearing only a light

jacket. At 24 inches, it

is one of the widest

monoplane cockpits around.

The

huge spar ran under my

knees and the seat angle

approached the so-called

semi-supine configuration.

This means your feet are

really out in front of you

and higher than on most

aircraft. This supposedly

makes it easier to

tolerate "G" forces.

Looking

around, I couldn't see a

thing on the ramp if it

was smaller than a JetStar,

so we cranked the seat

back forward to give me as

much height as I could get

inside the glass. The

prototype uses a canopy

which Dan Rihn says,

"...we just happened to

have laying around and

don't know what it is

for..." and is several

inches lower than that

which is in the drawings

or which will be available

for the airplane. That is

important because, as I

flew it, the airplane is

too blind for a monoplane.

Because of it's width and

low seating position, the

airplane is much blinder

than a Pitts during ramp

operations. It makes a

wide runway seem narrow

and two more inches of

sitting height should fix

that.

I have

a bad back (doesn't every

body?),. so I wadded up a

spare jacket and put it

behind my back as a lumbar

support. More on that,

later.

Locking

the canopy down (Dan says

a sliding version is

designed and in the

plans), I toggled the

primer and hit the start

button, immediately being

rewarded with a throaty

roar from the region down

by my feet. One of Shaw's

contributions is an

unusual offset control

stick arrangement he first

had on his Swiss Akrostar.

It looks weird, but, as I

wrapped my hand around it

to taxi, I was surprised

how natural it felt. The

throttle, however would

have benefited from being

relocated forward an inch

or so.

The

tailwheel ratios are dead

nuts on. The Aviation

Products 4" tailwheel is

small enough, cracks in

the pavement are felt,

but, otherwise it is

delightful in the way it

lets the pilot control the

airplane. Most airplanes

fall in a range, when it

comes to tailwheel

steering, with none of

them being bad. However,

when a good one comes

along like this, it points

out how much further the

rest have to go.

On

Scottsdale's 50 foot

taxiways, I had to really

exaggerate my "S" turns to

see ahead. Even in a

Pitts, a gentle turn opens

up a sight window straight

down the taxiway. Not so

the One Design. Dan is

aware of this. Since the

airplane is going to a

wide variety of pilots on

different types of

airports, the assumption

has to be it will see its

share of narrow runways

and green pilots, so the

vis has to be fixed.

Cleared, I rolled out on

what I estimated to be the

runway centreline and

gently brought the power

up. 'Sure felt like a 180

pulling out there! As we

rocketed down the runway,

I eased the tailwheel off

the ground and kept

increasing backpressure on

the stick to hold a

slightly nose high

attitude. I never did let

the tail get high enough I

could see over the nose.

At some point, the

airplane skipped once and

a little more pressure put

it off the ground and

climbing.

It was

instantly obvious there

was no reason to drop the

nose and let the airspeed

build. The challenge was

keeping the speed down and

that meant increasing the

deck angle by a bunch. A

big bunch! Chris had said

100 knots was a

comfortable climb speed

but I hadn't paid any

attention to the airspeed

at all until I had it

established in a climb

that seemed to look and

feel good. It was

indicating 115 knots! I

pulled up to 100 knots and

found myself pointing up

at a ridiculous angle. At

the end of the runway I

had an easy 1,000 feet and

by the time I was ready to

change frequency, I was

going through 4,000 feet.

I had

been told the airplane had

a tremendously high roll

rate, so I was very

conscious not to tweak the

ailerons and I kept

looking for the "balanced

on the head of a pin"

feel, but never found it.

On climb-out I could feel

a lightish pitch input,

but the ailerons felt

fairly natural, especially

if I rested my hand on my

knee and finger-tipped the

stick below the stick

grip.

A

Decathalon or Citabria

pilot might be well

advised to take a ride in

something like a two-hole

Pitts or Extra 300, just

to get themselves

introduced to the world of

light, quick controls. As

it happens, the One Design

presents absolutely no

problems in those areas,

as long as the pilot is

prepared for light

controls and can control

his movements. If he is

ham handed and prone to

panic, he could possibly

get a PIO going on his

first flight. If he does,

the fix is obvious...let

go, the airplane will

damp-out and take care of

itself.

I

wanted to get a stop watch

on the climb rates, but I

was already so high, I

dropped the nose and

twisted around in a diving

spiral, to get rid of a

couple thousand feet. In

the spiral, I could see I

would have to watch the

prop since it was fine

enough the rpm built fast,

when nose down. The speed,

on the other hand, was

easy to keep in check.

I found

at 100 knots, the airplane

climbed at about 1,400

fpm, and reducing the

speed to 90 knots put it

right at 2,000 fpm. I

didn't go any slower

because the angle gets so

steep it is dangerously

blind.

Level,

I slowly pushed the

throttle to the stop and

watched as the speed and

rpm built up. It was still

accelerating through 160

knots and and the tach was

pegged at 3100 rpm and I

was unwilling to push

someone else's engine any

faster. Obviously, it

could stand to have a

couple inches of pitch put

in it, although the

serious akro types are

happy as clams putting

3,200-3,300 rpm and up on

their engines.

The

initial part of the flight

had been done under great

duress because it had all

been right side up. I

fixed that at the end of

the speed run by pulling

hard upward, watching as

the nose whipped into the

vertical, as indicated by

the wingtip attitude

indicators. At this point,

I had yet to do anything

with the ailerons other

than normal flight

manoeuvres, so, I wasn't

ready for the world to

disappear, when I hammered

in what I thought was full

left aileron. With

absolutely no hesitation

whatsoever, the wings

ripped, absolutely ripped,

around the horizon

screwing up any form of

planning I had in mind.

Since I

had entered out of level

flight with no extra speed

in the bank, I had planned

on doing only a half

vertical roll and

hammerheading out, but to

this day, I don't have the

slightest idea how far I

went around, but it was

more than once. When I saw

what was happening, I held

it in for a second, then

centred the ailerons

instantly. The airplane

stopped so quickly, again,

I wasn't ready for it.

At that

point, I felt suitably

humbled and pulled over

the top, doing a half roll

on a downline, while

building speed.

On the

way out to the practice

area I had played with the

controls and found the

airplane to have

absolutely no discernable

adverse yaw, so rudders

were redundant in aileron

rolls. With that in mind,

I let the speed build to

160 knots and brought the

nose up high intending to

do two full-deflection

aileron rolls. Stick to

the side, I was amazed at

how fast it went around.

It was significantly

faster than even a Pitts

snaps. Dan says it has

been timed at 420 degrees

a second, where an S-1S is

about 180 degrees. Wow!

I did

the same thing again, this

time leaving the ailerons

in for four rolls and,

when I snapped the stick

back into centre, causing

the airplane to stop just

as quickly, my brain did

at least two more circuits

before it stopped. Serious

roll rate! What makes the

ailerons even neater is

that besides being fast,

there is no inertia at

all. When the ailerons are

poked, the wings

immediately respond, and

when the ailerons are

released there is

absolutely no tendency for

the wings to keep on

moving. Point rolls are so

precise and easy its hard

to keep your eyeballs in

their gimbals!

After

doing some investigation

of the controls, I

realized the airplane is

really unusual in that

unless the pilot asks for

a high roll rate, he'll

never know it is there.

The stick ratios,

break-out forces and

travel are such that a

pilot could fly the

airplane for years in a

normal fashion and never

have an inkling the

airplane has such

phenomenal roll available.

This is

not true of the elevator

forces. The stick gradient

for the elevator force in

positive flight is flat

enough that it gives the

impression of falling off

slightly. As "G" is

applied, it feels as if it

gets progressively easier

to add the next "G".

Again, this is no problem

except for the

"non-sensitive" (read: ham

handed) pilot. The first

few times a Decathlon

pilot loops the One

Design, there is a high

probability he will make

himself a lot shorter

unless he lightens up on

the stick.

Later

on, in doing outside work,

I found the outside

elevator forces to be out

of balance with those

inside. In other words, it

was much easier to pull

than it was to push. Dan

says this has been a

common comment and has a

fix in mind.

The

first time I rolled upside

down I was first surprised

at how much forward stick

it took, but wasn't

surprised at how

effortless the airplane

flew with the wheels

pointed up. With the stick

pressures as they were, it

was easy to drop the nose

a little and get a few

extra numbers, which

naturally led into a

healthy push, up and

around. I was watching the

airspeed, as the nose went

up and trying to connect

that to what I was feeling

in my hand. I initially

pushed 3.5 negative, since

I knew a Pitts would

easily motor over the top

with that load, but I was

pushing so hard to get it,

I didn't want the speed to

fall off and me not feel

the "G" availability go

away. Doing outside loops,

most airplanes telegraph

how much G they have

available through the

stick by building and

lightening pressures. The

One Design didn't lose

nearly the speed I had

expected and motored over

the top with something

like 80 knots showing,

when I only started at 145

knots.

I then

went ahead and pushed,

again aware of the extra

pressure. I just treated

it like a Pitts, getting

as much pitch rotation as

felt good at the top and

played the "G" load to

give 150 knots at the

bottom. It went around

like it was a mechanical

toy, with only minor

inputs from me. I have no

idea whether it was

actually round, but it

sure felt good.

I

noticed the airplane

didn't accelerate as

quickly as I had expected,

when going down on the

outside loop, so I pulled

nose high and slowed it

down, planning on doing a

split "S", so I could hold

a vertical downline and

watch the drag rise. At 60

knots, I resorted to habit

and banged a lot of

aileron in, since most

airplanes need it at that

speed. Again, the One

Design tweaked my nose and

went around so fast, I

almost missed inverted.

There is no speed at which

the airplane doesn't have

lots and lots of roll

left!

Letting

the nose point straight at

the ground power-off, I

watched the speed build

and found it very similar

to a biplane, which both

surprised and delighted

me. At about 160-170 knots

it begins to get draggy

and doesn't want to run

away from the pilot. Since

so many of the pilots

building this airplane

won't be experienced in

high performance

monoplanes, that's

probably a good feature,

although it might limit

the energy available to

the guy wanting to work

into higher aerobatic

classes. I know some folks

have flown the unlimited

known in the airplane with

no problems, so the drag

rise must not present a

serious problem.

Almost

everyone who flies the

airplane comments on a

super pronounced

root-stall buffet, when

pulling "G". It's hard not

to comment, since, when

the airflow separates at

the root it really gets

your attention. The

airplane doesn't react by

doing something stupid. In

fact, it normally doesn't

do anything, but it feels

as if there is a

mechanical shaker beating

on the airplane in the

vicinity of your feet. I

got it in some vertical

pulls and in some screwed

up snap rolls, but

otherwise didn't feel it

to be a problem. Dan says

he was trying to get by

without any fairings in

that area, but obviously

will have to add them.

In

normal stalls, the

airplane comes down to

about 50 knots, shudders a

bit and starts mushing. In

accelerated stalls in

turns, it does the same

thing, but rather than

rolling to the outside,

like most airplanes would,

it simply holds the bank

and mushes.

The

airplanes has so little

dihedral effect in any

situation that you can sit

in level flight and walk

the nose back and forth

with the rudders and not

have either wingtip leave

level flight. Later, when

I was coming back to the

airport and wanted to pull

my jacket-lumbar support

under my butt for more

height, it proved a real

challenge because I

couldn't bring up a down

wing with just my feet.

Interesting!

We were

working within a fairly

tight time constraint and

I only had 45 minutes to

play with the airplane,

not nearly enough to delve

into many secrets of its

soul. For instance, I

found my snapping

techniques and the One

Design's were not

necessarily the same. I

had a tendency to bury the

stick too much, when all

it took was a tweak back

followed by unloading the

stick. Given a few more

minutes, it was obvious

the airplane would snap

clean and stop even

cleaner.

The

same thing was true of the

spins. I did inside three

turn spins right and left

and noticed it was fairly

asymmetric, with them

being noticeably

different, one being more

on-axis than the other. It

was the inverted spins I

wanted to work with.

Someone had told me to do

a flat spin, which I

normally won't do in a

strange airplane without

more assurances. But, they

said I wouldn't believe

it. I hadn't planned on

doing an inverted spin,

but I was in the process

of screwing up a

hammerhead, so I went

ahead and pushed, keeping

the left rudder in and

about quarter power. The

airplane snapped into the

spin so cleanly and

stabilized so quickly

there was practically no

transitional spin at all.

Then I played with the

power, watching the nose

go up and down.

When I

killed the power to

recover and initiated

rudder and stick

movements, the airplane

stopped spinning so

quickly, I found myself in

an inverted, glide before

I got the controls fully

reversed and had to

neutralize everything. I

hate to make blanket

statements, but the

airplane appears as if it

will recover cleanly all

by itself hands-off.

The

airplane does everything I

know how to do so easily

and cleanly, it could have

been an Extra 300S. It

obviously doesn't have the

speed or the vertical, but

for the audience it is

aimed at, they'll be hard

pressed to see the

difference and it's a

darned sight cheaper.

When I

came in to land I lucked

out and was cleared to

land from five miles out,

so I motored right in and

set up for a power-off

approach. I shut things

down opposite the end of

the runway and yanked the

trim full up, since it ran

out of trim at 80 knots

and I wanted about 75

knots. As it was, it takes

a little time to get it to

slow down below about 110

knots.

I flew

a Pitts-type circling

pattern, turning all the

way to the threshhold and

the airplane felt as if it

liked that kind of

approach, since it stayed

on speed and profile like

it had been there before.

As I rolled out in ground

effect and on centreline,

most of the runway

disappeared and I

concentrated on keeping my

head back so I could see

both sides in my

peripheral vision. I

didn't know for sure where

the ground was so I

gingerly flared and felt

at the same time.

I felt

the mains kiss off the

pavement and mentally

chastised myself for

setting up a bounce and

kept working to hold a

three point so the

airplane would come down

out of the bounce

straight. I worked for

what seemed like a long

time, then I realized I

wasn't coming down because

the airplane was rolling

on the pavement. I had

originally planned on a

touch and go, but called

the tower and said I'd

take that one. I'm no

fool.

The

foot work required during

takeoff and landing was

Citabria-simple, but the

lack of visibility made

the landings much, much

more difficult than

necessary, and that's

coming from a long-time

Pitts pilot.

One

thing everyone should keep

in mind about the One

Design: It isn't fair to

compare the airplane to

any other, if only because

it isn't designed to

compete with other

airplanes. If the One

Design class concept

works, its primary

competition will be

itself. So the question of

how it flies should be in

relation to the pilot

audience it is meant to

address, not in relation

to the hottest or newest

designs out there.

One of

the intriguing side notes

to the One Design is the

adaptability it offers to

other kinds of pilots and

homebuilders. Although it

was designed as a bargain

basement Sukhoi-killer,

what it also offers is a

tremendous amount of fun

and performance in an

airframe that is basic and

simple to build. This is

also one of the few

airplanes that can

actually be built right

from the plans utilizing

no pre-made components, if

so desired, which makes it

a real boon to the budget

minded. In all

probability, the material

costs alone of the

airframe are well under

$5,000, if no pre-made

components are used.

At this

time Aircraft Spruce is

ramping up to be the

exclusive supplier as well

as the plans seller for

the IAC. Although they may

be the exclusive plans

seller, as soon as the

plans get out in the hands

of builders, suppliers

will pop up who are ready

and able to crank out

tails or wings, landing

gears, etc.

I also

predict the airplane will

become the basis for all

sorts of hotrod

modifications, the 180 Lyc

being the first and some

sort of six cylinder bomb

won't be far behind. Dan

is already getting

pressure to do a

two-place, but that's such

a massive project, that's

not a modification, that's

a new airplane.

If, as

anticipated, a huge number

of builders get into this

project, the economies of

scale are going to result

in tooling being available

that will take the fear

out of some of the harder

processes, like drilling

the main wing spar bolt

holes. That process alone

has always terrified Laser

builders.

The One

Design is exciting, if

nothing else because it

offers serious monoplane

performance for sport

pilot and akronut alike.

Also, whether the One

Design class concept takes

off or not, the airplane

gives homebuilding a new

plansbuilt design that's

within the reach of many

possible competitors who

were previously

financially grounded. Now

they can get in there and

mix it up with the big

guys.

As I

look back at what I've

written, I think its

necessary to make one more

comment. We've all become

so accustomed to Sukhois

and Extras, Lasers and

Staudachers that we're

guilty of being a little

too blaze' about what

makes outstanding

performance. We're

measuring performance

against airplanes that are

available to a select few

and I've got to tell you,

the margin between the One

Design and the super

machines is so small that

only the established

unlimited top dogs are

going to be able to tell

the difference. So who

cares. That's not us

little guys.

The

first time a Citabria

pilot pulls vertical and

hammers the airplane into

a double vertical roll,

his mind is going to throw

off blue sparks as it

yells, "It can't possibly

get any better than this!"

And I'll tell you

something, in the real

world most of us live in,

it doesn't get any better.

Now if

Dan could just put another

wing on it for us old

guys.