The Kimballs, Jim the

elder and Kevin the son,

are interesting folks.

Working out of their

private grass strip in

Zellwood, Florida, they

have carved something of a

special niche for

themselves within the

world of antique aviation.

Now, with the Pitts Model

12, known by some as the

Macho Stinker, they are in

the process of whittling

an equally impressive, and

typically unique, niche in

the world of homebuilding.

As the

purveyors of kits and

components for Curtis

Pitts' most recent biplane

design, the hairy chested,

round-motored Model 12,

they have applied their

deep knowledge of round

motored biplanes to their

version of a sorta-antique

for the homebuilder. Of

course, being a Pitts,

it's an antique with

spunk.

Before

Curtis was even close to

finishing the Macho

Stinker back in 1996,

Kevin and Jim were

standing on his doorstep

looking over his shoulder.

They were looking for

something new to add to

their repertoire and the

Model 12 tickled their

fancy. They came away with

a set of plans and started

building at the same time

as Curtis and his Biplane

Mafia.

The

Kimballs were not

strangers to biplanes. In

fact, in the years since

Jim bailed out of the

electronics wholesale

business in an effort to

save both his health and

his sanity, biplanes have

been central to their

lives. Running an

electronics company with

200 employees and an

eccentric owner had taken

it's toll and Jim simply

walked out the door and

decided it was time to do

something else with his

life. However, to keep

himself busy while he was

picking a direction, he

purchased a basement full

of parts which were

propertied to be a

Staggerwing, when

assembled, and began

working on what is widely

regarded to be one of the

most labor intensive

airplanes in the world to

restore. The result was

that he didn't have to

pick a direction for his

life. The direction came

looking for him in the

form of antique airplanes.

He was good at what he did

and he loved it.

Having finished and sold

the Staggerwing, he

purchased a Stearman and

began restoring it with

the goal of selling it for

a profit. That was the

last airplane he had to

purchase. From that point

on people were banging on

his door seeking his

skills to be applied to

their aircraft. That

single Stearman was the

first of 25 Stearman, 6

Staggergwings and

everything in-between. In

total, since they moved to

Zellwood in 1982, they

have restored over 80

antique airplanes, Cub to

Staggerwing and all of

those which have been

entered in judging have

won awards. The SM8

Stinson they built to be

an award winner cleaned up

at Sun n Fun the only year

SnF had a trophy for

overall winner.

Kevin,

who is 32 years old with

two tykes of his own, was

a tyke himself when he

started helping his dad.

"We have pictures of me

rib stitching when I was

eight years old." By the

time he graduated high

school and was ready to go

off to the University of

Central Florida to study

engineering, he had built,

rebuilt or designed

practically every part on

an airplane. This put him

in a different category

than the rest of his

mechanical engineering

class. "It was really

frustrating because the

professors would

constantly be designing

things that couldn't be

built. To them a bolt was

a bolt, there were no

different types or sizes,

or they'd come up with an

assembly on paper in which

aluminum was welded to

steel. They just didn't

get it."

One of

the reasons the Kimballs

decided to take on the

Model 12 project was

creativity and pure

practicality. "We were

tired of building things

that had to look and be

built like something else.

Our first serious

homebuilding activity was

building the Model Z Gee

Bee, but even there we had

to conform to older

practices in many areas

just as with the antiques.

In some of the antiques

we'd have to bolt a seat

to a 1/4" plywood floor,

really stupid, but that's

the way it had originally

been done, so..."

As the

Model 12 at Curtis' was

coming along, the Kimballs

began negotiating to buy

the rights to the design

to incorporate it into

their business. What they

didn't know, and Curtis

had forgotten, was that

there was a clause in the

contract under which which

he had sold the earlier

Model 11 Super Stinker

rights that gave that

purchaser first right of

refusal on all further

Pitts designs. They

exercised their option and

the Kimballs found

themselves looking for

another way into the

homebuilt biplane market.

However, when they then

negotiated to become the

parts supplier in support

of the individual who was

selling the plans, they

found themselves scratch

building Model 12 parts

anyway.

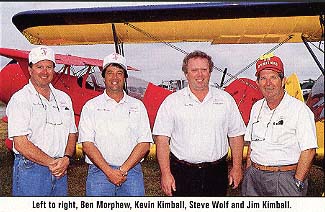

As soon as the original

Model 12 was flying, Ben

Morphew, a long time

homebuilder and G-junkie

from Dallas, journeyed

down to Homestead to fly

it. On his way back home

he called the Kimballs to

get them started on

building a Model 12

airframe for him. He,

however, had some changes

he wanted made. Morphew's

input, coupled with

several items which

surfaced once the

prototype was flying (e.g.

the original motor mount

had to be 11 inches longer

than calculated for CG

purposes), set in motion a

subtle redesign (with

Curtis' blessing every

step of the way) that

resulted in the Model 12

which the Kimballs offer

in kit and pre-finished

component form. It should

be noted that there are

actually two versions of

the airplane now: The

original, as shown on the

plans and the Kimball

version for which plans

are not available.

However, Kevin and Jim

make components for both

versions and, where

possible, make their parts

so they'll fit on the

original design.

Morphew, being a long time

aerobatic pilot who, among

other things, owned the

original Super Stinker

before selling it to

Aviat, wanted an airplane

that more closely fit his

personal definition of

what a sport biplane

should be. Where Curtis

had designed the airplane

to be "...an old man's

airplane", as he put it,

something which was much

tamer than Pitts usually

are, Ben wanted to put

some of the well known

Pitts hot-sauce back into

the design. Among the

changes he wanted were

shorter wings and longer

ailerons for more roll

rate. He also wanted the

canopy modified, something

which the Kimballs already

had underway.

Changes

from the original include

clipping a foot from each

wing and maintaining the

same number of ribs so

they were moved closer

together. The I-struts

were relocated to balance

inboard/outboard bending

moments. The ailerons were

extended clear to the tips

and run in one bay closer

to the fuselage. This

produced a 22 foot span

(an S-2 Pitts is 20 feet

and a Skybolt 24). At the

same time, they took most

of the dihedral out of the

lower wings leaving only

about half a degree and

that was mostly to avoid

the "droopy" look zero

dihedral wings tend to

have. As they proceeded

with the redesign, Curtis

urged them to design metal

ailerons as they'd be

lighter and easier to mass

produce than the wooden

ones on the original

airplane. The kits include

these metal ailerons

although the plans show

wooden ones.

To get

the C.G. problem worked

out and shorten the motor

mount, the Kimballs did

some redesign of the

fuselage which included

relocating the

pilot/passenger, in

relation to the wings. The

net result was that the

engine came back and the

tail came forward making

the airplane 10" inches

shorter. Kevin

re-calculated the tail

volumes and increased the

size of the rudder to give

the same amount of

authority the original

had.

The

canopy on the original

airplane was actually an

afterthought as the Macho

Stinker was supposed to be

an open cockpit airplane

until it was within

several months of flying.

At that point the sheet

metal was already

finished, so the canopy

wound up sitting on top of

the sheet metal combing

and used a locking and

sliding mechanism even

Curtis wasn't satisfied

with. Also, with the sheet

metal combing up so high,

the cockpit had a definite

gopher hole feel and

visibility suffered. On

the Kimball version, the

sheet metal combing is

eliminated and the canopy

comes clear down to the

longerons, ala Christen

Eagle. It is bonded to a

4130 frame and includes a

separate windshield for a

couple of reasons. "We

wanted the windshield so

in case you ever lost a

canopy, the windshield

would still be there

deflecting wind. Also,

without the windshield,

the canopy only has to

come back four inches to

clear the wing before

opening."

The

canopy also has an

intermediate locking

position so the airplane

can be taxied with it

partially open. Taxing a

bubble cockpit airplane of

any kind on a warm, sunny

day (the kind we all like

to fly on) with a canopy

that can't be opened is

too much torture for most

people.

By the time the Kimballs

began working with the

Vendenyev M-14P radial

engine from Russia, most

of its quirks had been

encountered by the

aviation movement, but not

all of them had been

worked out. The

difficulties with the

engine centre on three

things: first, the fact

the rocker boxes aren't

drained puts a lot of oil

into the bottom cylinders

which promotes hydraulic

locks on starting. You

have to be really careful

you clear the induction

tubes and cylinders.

Second, the starting

system is pneumatic which

requires a constant supply

of high pressure air.

Third, the engine fittings

are either metric or just

flat weird so hooking it

up to SAE or AN fittings

required a lot of

conversion gymnastics for

those putting the engine

in a non-Russian airframe.

A number of homebuilders

have faced and conquered

these problems and

Kimballs tossed their

accumulated knowledge into

the pot and brought all

the fixes together under

one roof. Now, anyone

seeking to hang one of

these engines on a

homebuilt (they've

actually put one on a UPF

WACO), only has to make

one phone call to solve

all their problems.

The

Kimballs interconnect all

of the rocker arms and

drain the induction tubes

into a common drain. Then

they have a gear pump that

in 30 seconds after shut

down scavenges the sump

completely drying it out

and pumping that oil into

the oil tank. The oil tank

has a shutoff valve that

stops oil from gravity

feeding into the sump

which eliminates the

problem of oil pooling on

the back of the bottom

pistons and seeping past

what they say are weak oil

rings to flood the lower

cylinders. To eliminate

the fear of cranking the

engine with the oil turned

off, the shut-off valve

has a micro-switch that

disables the starting

circuit until the valve is

turned on and oil starts

into the sump. The

Kimballs have been using a

similar system on

antiques, especially those

with Wright engines, for

years.

The air

start system depends on a

smallish bottle

pressurized to 800-900 PSI

which works through a

distributor to pump air

into cylinders in

sequence. The Kimballs

have a complete starting

system kit mounted on a

single firewall panel that

the builder just takes out

of the box, bolts to the

firewall and hooks up. The

scavenger hunt to find the

right parts has been

eliminated. One thing the

Kimballs don't use, which

Curtis did, is a shut off

on the air tank. That's

the only way to guarantee

it won't bleed down and

they say a shut off valve

is probably in their

future.

As for

the hardware to mate the

engine to "normal" hoses,

electrics, etc., they've

worked with a number of

folks and come up with a

complete fitting kit that

makes it hook up like it

was a Lycoming.

When

the airplane made its

public debut at Sun 'n Fun

the super slick cowling on

the Kimballs airplane drew

more than its share of

comments. "The problem

with making the cowl is

that the firewall is a

really weird shape, so the

cowling can't be round and

fit. We did a CAD-CAM

model of the cowling,

blending it from a

Twin-Beech sort of ellipse

to the firewall in the

computer. Then we

generated individual cross

sections at each station

and a friend with a CNC

cutter cut the cross

sections out of foam. We

stacked them up like a

wedding cake and sanded

them to shape. That went

to our fibreglass guy who

made a mould for us. The

final weight of the

cowling is 24 pounds but

we'll do it in carbon

fibre, if someone wants

it. That saves about 13

pounds but it runs about

$120 per pound saved."

The

fire wall on both versions

of the Model 12 are the

same so they make the

cowlings long enough that

they'll fit the originals

while those building the

newer version have to

whack a section off the

back of the fibreglass

unit. Kevin says they are

planning on putting a foot

square door on each side

of the cowling to make

maintenance easier.

The

massive landing gear

sports a unique

streamlining technique: A

custom extruded rubber

fairing bonds to the rear

of the gear leg and the

brake lines run through

holes in the extrusion.

The

kit, in its complete form,

has all the welded

components finished and

powder coated. There is no

welding to be done. The

ailerons are assembled and

finished and instrument

panels are ready to be

punched for instruments.

The turtle deck is

completely pre-formed. The

wings come as a wood kit

with the spars finished

and drilled but the ribs

have to be assembled. The

Kimballs have designed a

cute rib assembly jig. The

kit includes seven rib

jigs that are 3/4"

particle board with the

outline of the rib routed

deeply into the board.

Holes are drilled in the

bottom of the channel for

each leg of the rib truss.

When the jig is used, it

is blocked up off the work

bench by 1 by 2 scrap.

Short pieces of wooden

dowels (supplied) are

inserted in the holes in

the rib channels and the

rib is then assembled.

When the gussets (supplied

precut as is all the

corner blocking) are in

place, the jig is simply

tapped down against the

work bench and the dowels

force the ribs out of the

jig.

Many of

the parts, wood and metal

are laser cut with the raw

edges of the metal that

won't be welded dressed

back to eliminate any

hardening from the

laser-cutting process.

Even the plywood nose ribs

are laser cut. The leading

edges, by the way, are

plywood and formed for the

Kimballs by Steve Wolf.

As of

this writing, they had

delivered nine kits since

the first of the year and

had orders for 21. This

doesn't include numerous

parts kits they've

produced for those who are

scratch building from

plans, which is another of

the airplane's strong

points. An individual

doesn't need to pony up

all the money for the kit

because they can scratch

build it a piece at a

time. 'Have enough money

for some steel tubing?

Start building the

elevators. The money can

go in at the rate an

individual wants. The

engines, incidentally, are

still reasonably plentiful

and the prices have

plateaued for the last

couple of years at $16,000

for a brand new one.

With

all the formal stuff

behind us, it's time to

talk the important stuff:

How does it fly?

When

Steve Wolf and I got ready

to saddle up (Steve is

campaigning the airplane

for the airshow season) we

had a serious discussion

about which seat I should

sit in because he was

worried about the air

supply for starting. I

didn't really care which

seat I was in, having

flown it from the rear in

the past, so I scrambled

up front making any

starting problems Steve's

fault. I didn't realize at

the time what I was

getting myself in for as

the front seat is so wide

and low it is really, as

in REALLY, blind. Oh,

well. Between that and a

gusty, 90 degree crosswind

it would be a test for

both me and the machine.

The

start went exactly as

planned (I could've done

that...maybe) in that the

pneumatics kicked the

engine into life in just a

few blades. Ben had told

me if it doesn't start on

the first several

revolutions, stop because

something else is wrong.

As soon as the engine was

running, the engine-driven

pump started replacing the

air it had used starting.

I'm

glad I had set in the back

seat of the new airplane

because the visibility

back there is greatly

improved from the

original. In fact, it is

no worse than most other

taildraggers. Although the

length and width of the

nose gives the impression

it's blinder, it's not. Up

front, however, with the

huge instrument panel (the

cockpit is nearly two

people wide) and low

windshield with wide

framing, I had to S-turn

more deeply than usual to

make sure we didn't taxi

over a hangar or something

of similar size.

Fortunately, the Aviation

Products steerable

tailwheel made ground

handling a breeze...even

in the breeze.

Takeoff

can only be described in

two words...a blast! What

an absolute kick in the

shorts! It's not often I'm

caught unawares by an

airplane on takeoff, but

this one did. I brought

the power up smoothly

working to keep the tiny

wedge of runway I could

see right where it was on

the windshield frame. When

the throttle was about

2/3rds of the way in, the

prop went into governor

range and the surge felt

like I'd just slapped it

into afterburner. I was

congratulating myself on

doing such a great job and

had just started to pick

the tail up when the

airplane lost patience and

leaped/clawed/bounded into

the air. I was behind the

airplane in no uncertain

terms. Wow! I doubt if the

process had taken more

than 4-5 seconds. In less

time than I could think

about it, the airplane was

rocketing through 300 feet

and, between the hard

crosswind and

wrong-turning prop, I was

clear over the right side

of the runway.

I just

let it find a groove to

climb in and I guessed we

were going up about 2,500

fpm. Then I looked at the

airspeed. We were doing

130 mph! We blasted

through pattern altitude

less than halfway up the

runway and doubled pattern

altitude even as I turned

out to find a legal piece

of airspace in which to

play.

Unfortunately, we had an

unpredictable low cloud

condition so, as we

climbed on top, Steve and

I both kept a nervous eye

on where we thought the

airport was. Getting lost

in the local area is

always embarrassing.

On

takeoff we were showing

about 33-34 inches of

manifold pressure (it's

mildly super charged,

remember) which should

have given us the full 360

horses. And it felt like

it. Bringing the power

back to what Steve said

would give us a normal

cruise at about 13-14

gallons an hour left the

airspeed hanging at about

175 mph and it was truing

much higher than that.

I

wracked the wings back and

forth feeling out the

pressures and adverse yaw

and found you could tell

the difference in the

wings from the original.

It reacted to aileron

input much more quickly

and the roll rate was

noticeably higher. Since

Curtis had designed the

airplane to be more

gentlemanly than most of

his designs, when he

hinged the ailerons, he

didn't go as far aft on

the hinge point as his

other symmetrical "Super

Stinker" technology wings

because he didn't want the

ailerons that light. For

that reason, hustling

along at Bonanza speeds,

the aileron pressures are

higher than I wish they

were, a thought echoed by

Ben Morphew and a few

others. Kevin has said he

doesn't want to put spades

on it, but Curtis

reportedly told him he

might as well give in and

make the spades so he is

the one making the money

out of them rather than

someone else.

Incidentally, saying the

ailerons need to be

lighter is a relative

statement: Compared to

most "normal" airplanes

they are light enough, but

then, this isn't a normal

airplane is it? We're

talking rock and roll

here. Not foxtrots.

First

an aileron roll. Then a

positive-G 4-point. Then a

slow roll. Then a regular

four point. Then lay it on

its back and let it groove

into a hard left turn.

Yeehah! Steve told me to

loop it from level flight,

so I pulled with my right

hand and pushed with my

left and a curious feeling

coursed through the

airframe and into my body:

It was as if I was being

pulled uphill by a tractor

which had so much torque

and brute force it didn't

care that it was going up

hill carrying a heavy

load. It just kept on

chugging and I could feel

it pulling us up and over

and hardly giving up any

speed in the process. It

was as if I could feel the

lift vector that was

defying gravity shift

slowly from the wings to

the prop blades and back

to the wings again.

And

speaking of props. They

are using the MT composite

three blade prop and

recommend either those or

the similar Whirlwind

rather than the original

two blade units for a

number of reasons. The

original Russian props are

time-limited and are

getting harder to find at

a decent price. Also by

actual pull tests (a

fishing scale between the

tail and a stout hangar),

the three-blade composites

are putting out 25% more

thrust. Right. As if the

airplane needs more

thrust. The Hoffman three

blade is also a good and

less expensive

alternative.

We kept

watching the cloud layer

playing with the ground

and decided it was a good

idea to go back and shoot

some landings. The bottom

edge of the cloud layer

was right at pattern

altitude, so, as I came

rocketing down hill, we

had a real feeling of

speed as we flashed down

through the openings at

200 mph plus. At first I

thought I was going to

have trouble slowing it

down, but bringing the

power back and letting the

prop flatten out

practically throws you

forward in your seat.

Also, there were other

airplanes in the pattern

and about the only way I

could keep track of them

was to make sure I knew

where one was and pull the

airplane hard into a space

behind him which I was

positive no one else

occupied. That slowed the

airplane down too. Low

visibility in a blind

airplane and a crowded

pattern really keeps your

head on a swivel.

I had

to make the first approach

behind some yo-yo who was

making a cross country out

of his or her approach. I

avoided centerline and

kept the runway in sight

by flying a steep angle to

final from the left which

let me see the runway and

the traffic at the same

time. I had no idea what

the glide angle would be

so I kept it intentionally

high intending to slip

down in the usual Pitts

landing. This is what I

did. Sorta, but between

unfamiliarity and the

crosswind pushing us

towards final, it wasn't

very pretty. I wanted to

hold 100 mph, but wasn't

working too hard at it as

I'd already seen that any

time I wanted to kill

speed, all I had to do was

pull the power and hold

the nose in a given

position. The prop took

care of the rest.

As the

ground came up at me, I

brought it around and

lined it up with the

runway and did something I

tell my students never to

do: I was staring at only

one side of the runway.

Usually I like to look at

both sides to judge drift

and alignment. This time,

however, it took too long

to glance form side to

side, so I just snuggled

up against what I could

see of the left side of

the runway and held that.

I was a

little fast and the gusts

were doing their best to

push us off the runway,

but the little airplane

wouldn't let them. As with

all Pitts designs, it's a

terrific crosswind

airplane.

I

thought I had the three

point attitude nailed ,

but I kissed off the

ground with the mains

giving us a nice little

bounce. No big deal, just

keep it straight and don't

let it drift. Proing! It

was back down again and it

stuck this time. My feet

kept waiting for something

to happen, as it rolled

out, but other than the

occasional tap, it didn't

need anything.

I knew

a Cherokee had taken off

just in front of us and I

debated whether to make it

a touch and go, knowing

I'd catch up with him in a

heart beat. but, I

couldn't miss the

opportunity to do another

one. Power coming up, prop

surging, we leap off and I

make a slight right turn

as soon as the gear clears

looking for the Cherokee.

I kept climbing and

turning and finally

located him about 100 feet

off the right side of the

runway where he'd let the

wind push him. I just kept

the nose and power up,

whizzing up to pattern

altitude and turning over

him while he struggled

through two hundred feet.

On this

approach the wind was

really working us but I

was determined to do

better. I didn't. I kissed

it off the mains again and

hung there for a second

until it came back down.

Same deal as last time as

the airplane didn't do

anything stupid. The

conditions couldn't have

been too much worse and I

was doing much less than a

sterling job but the

airplane still behaved

like a gentleman. A very

macho gentleman.

Is this

a hard airplane to fly?

It's no cub, but other

than the lower than normal

visibility and higher than

normal climb rate, it's

much easier than any other

Pitts to fly. In fact, I

think I'd put it right in

with the Skybolt in terms

of being a terrific

airplane that can be flown

by most people. And then

there's the other question

about the prop turning the

"wrong" way. Yes, I

noticed it, but only if I

thought about it. The rest

of the time you just use

which ever foot is needed

to do what ever it is

you're trying to do.

How do

I feel about the airplane

in general? Perhaps my

wife and soul mate Marlene

summed it up best when we

were standing by the ramp

waiting for the two Model

12's to arrive at Winter

Haven. As they taxied up

and the Vendenyev's were

making that characteristic

Bearcat rumble, she looked

across the top of the car

at me with big round eyes,

grinned and said, "Now,

that's where the word

'bitchin'' came from."