(Aviat-Modified Super

Stinker)

As I turned off the runway

on to a taxiway, my mind

hardly heard me as I

automatically spoke to

ground control. Most of my

brain was doing arithmetic

of an entirely unrelated

nature.

A voice

inside my head was saying,

"Okay, so I can probably

build up an IO-540 for

around $15,000. It doesn't

have to be a 300 hp

version. And all the

tubing won't cost $1,000.

The wing wood may go close

to $2,000. Cover costs

might..." By the time I

pulled up in front of the

fuel pits and Aviat's Lou

Meyer and VP of

Engineering and Special

Projects, Ed Saurenman met

me, I already had an

approximate total of what

it would cost to build one

of their unbelievable

S-1-11B/Super Stinkers

from scratch. This

airplane is the Super

Stinker on steroids, a

Super-Super Stinker, and I

wanted one badly.

It's no

secret I have a thing for

Pitts Specials. It's also

no secret that at

different times I have

professional ties to Aviat.

Yes, I have predisposed

opinions, but I dare

anyone to step out of that

airplane and not have

similar thoughts to mine:

This is one very serious

airplane. Kirby Chambliss

summed it up after flying

it when he reportedly

said, it flew as if it was

a monoplane with an extra

wing. Coming from a

confirmed monoplane pilot

and National Champion,

that's saying a lot.

But,

let's not get too far into

the aerobatic accolades

before recognizing several

other aspects of the

airplane that may well be

more important than the

fact that it is of

unlimited competition

calibre. First of all, the

airplane is the only

unlimited type airplane we

know of that can be

scratch-built from a set

of plans. What this means

to the homebuilder is that

costs can be kept to an

absolute minimum while the

final result is of world

class quality. By

utilizing Aviat-built

components, the project

can be moved a long a lot

faster, but that's not

necessary for the

budget-minded builder.

Also, the builder doesn't

have to be an acro-nut. He

can just want a simple,

great flying airplane that

he can say he built

himself.

In the

cost control department we

find big variables like

the engine itself. The

version I flew and which

lit my gotta-have-it wick

was powered by a high end,

Monte Barrett custom

IO-540 with 10.5:1

compression and a bunch of

other custom do-dads that

pumped it up to more than

305 hp on the dyno. And it

felt like it. Talk about a

stump-puller! But with an

airplane this light (1090

pounds empty), you don't

need that much engine. In

fact, when I flew the

Super Stinker in 1994,

when it first came out, it

was powered with an stock

0-540 reportedly putting

out around 230-240 hp and

it was still a killer

machine.

In some ways, building up

a six-cylinder Lycoming

these days, is no more

expensive than building a

four-cylinder. Ask anyone

who's building an RV-6 how

hard it is to come up with

a low-cost rebuildable

core for a four-cylinder

Lycoming versus the cost

for a low-end six

cylinder. Cores for the

low-compression 235 hp

0-540 go for a comparative

song with the 250 hp

version only slightly

more. Don't want to burn

so much fuel? Bring the

go-fast lever back a notch

or two.

A lot

of costs can be cut right

at the power-plant.

The

prop is another area where

costs can be cut. The

factory's S-1-11B had the

top dog of aerobatic

propellers bolted up

front, the Hartzell

composite aerobatic

series. This is a very

expensive propeller. Very

expensive! The prototype

Super Stinker, however,

had a garden variety,

two-blade, aluminium

Hartzell on board and,

other than the stresses it

puts on the crank in

aerobatics, is still a

good choice. Between the

two would be the

three-blade composites

from either MT or Hoffman

(available from Steen

Aerolab).

By

doing a little shopping,

this airplane could be

scratch-built for less

than $30-35,000 in Sunday

hell-raising form. The

airframe alone shouldn't

top $10,000 leaving the

final cost question being

one of engine and prop.

Using the

professionally-built

components from Aviat

raises the price but cuts

the building time by an

estimated 60-70%. Almost

every builder would have

to purchase the heavy,

spring aluminum gear from

Aviat as it is beyond the

backyard builder's shop

capabilities

But,

not everyone wants an

unlimited aerobatic

airplane. What about those

of us who don't care about

aerobatic competition? I'm

going to make a flat

statement here: This

airplane is so much fun to

take off and land that if

you do nothing more than

dropping the hammer on

takeoff to get your

adrenaline pumping, the

project would be worth the

effort.

On my

first takeoff out of

Scottsdale, I can honestly

say I wasn't prepared for

the effect of smoothly

moving the noise lever to

the stop. As the Monte

Barrett Lycoming began

pumping out the ponies, I

had the illusion I was

desperately hanging onto

the controls just to keep

from being left behind. I

had to concentrate to keep

the throttle forward so

inertia wouldn't bring my

hand back unintentionally.

But, we're getting ahead

of ourselves.

There have been a lot of

changes in the airplane

since Aviat bought the

rights for the airplane.

Since we flew the airplane

in Homestead, Florida

right after Curtis Pitts

finished it (see Sport

Aviation, May, 1994) the

design has gone through

several ownership changes

before landing at Aviat.

During the in-between

stages, Ed Saurenman, who

then was a partner in

Certification Specialists

in Wichita, put his

CAD-CAM expertise to work

and produced a complete

set of very thorough

drawings for the Super

Stinker. Those are the

plans Aviat is now

selling.

When

Stuart Horn took over

Aviat in January of 1996,

one of his goals was to

return the name Pitts

Special to the glory it

had enjoyed in years past.

His first step was to

purchase the rights to the

Super Stinker. His second

step was to spend a lot of

time with competition

oriented people, both

inside and outside of his

company, to revise the

lines of the airplane to

make them more easily

judged in international

competition. These changes

were primarily cosmetic

and straighten out the

lines of the airplane by

flattening the belly and

squaring off the lower

rudder surfaces. At the

same time they went to a

rakish, flat-wrap

windshield and laid the

seat back 20°. The end

result is a long, really

snarky looking airplane

that, if you put your hand

up to visually block the

top wing while looking at

its side view, it could

easily be a monoplane. The

plans they offer have

Super Stinker outlines

while the finished

components have S-1-11B

cosmetics. Aerodynamically

and structurally, they are

the same airplane.

The

second I stepped down into

the airplane to fly it,

the laid back seat was an

obvious change. In fact, I

could have used another

cushion under me for

visibility but it was

close enough. Lou pulled

the prop through a few

times and we cranked it.

The high compression was

obvious even at idle.

The

Haigh, locking tailwheel

of the Super Stinker has

been replaced by a tiny

steerable unit on a Doug

Dodge tapered rod spring

which makes ground

handling much more

convenient although I knew

I'd have to pay more

attention on landing.

The

inverted "J" control

stick, with its reverse

curve and dangling stick

grip proved to be a

fatigue problem from the

start. Lou said it was

left over from early test

programs and was on its

the way out. Configured

the way it is, even on

taxi there's no way to

slide your hand down the

stick and rest your arm on

a knee. It sounds like a

minor point but I was

surprised how tired my arm

and hand were after I

returned from the flight.

Rolled out onto centreline

with the throttle coming

up, I was treated to the

most amazing acceleration

I've ever felt in an

airplane. Actually, it may

have been the most

acceleration I've felt in

anything which includes

some fairly serious drag

cars. I would have

grinned, but was a little

nervous because it was

obvious the airplane was

getting ahead of me. The

tail blew itself off the

ground as soon as I

relaxed back pressure and

the airplane was off the

ground and screaming

upward before I had time

to think about it. This

was one takeoff where I

was definitely behind the

curve.

Later I

did the math: At that

weight and power, the

power loading was under

4.5 pounds/horsepower. No

wonder it was a rocket

ship!

I

glanced at the airspeed

almost as soon as we left

the runway and the needle

was racing through 100

mph. I guessed the best

rate to somewhere around

90 mph, but the deck angle

was already ridiculous so

I settled on 110 mph as a

climb. There was no VSI,

but I had nearly 3,000

feet between me and the

ground by the time we hit

the other end of the 7,000

ft runway. Aviat claims

4,000 fpm and later timed

climbs showed the rate of

climb may actually be

higher than that. Now I

was definitely grinning!

This

was truly astounding

performance. More

important, other than

feeling I was behind the

airplane, the skill

required during takeoff

had actually been minimal.

The airplane had tracked

straight ahead and my

primary duty had been to

simply grit my teeth and

hang on.

As soon

as it was off the ground,

the quick ailerons made

themselves known.

Break-out pressures around

neutral are low and,

because I couldn't rest my

arm on a leg, turbulence

made the weight of my hand

on the funny shaped stick

a factor. The wings jinked

a few degrees left and

right before I got the

message: be gentle. I'm

glad they're changing the

stick.

The

S-1-11B includes what has

become known as "Super

Stinker Wing Technology."

When designing the wings,

Curtis incorporated his

patented method of using a

thicker airfoil section on

the bottom wing so the top

one would always stall

first. This is the way all

symettrical-wing Pitts are

designed. However, when

doing this for the Super

Stinker, he came up with a

unique aileron design that

gives light, quick

pressures and phenomenal

roll rates without

resorting to shovels which

would hang below the

ailerons. Basically what

he did is hinge the

symmetrical ailerons well

back on their chord to get

the pressure down and then

profiled the nose of the

aileron in such a way that

the sizeable

aileron-to-wing gap

decreases to zero as the

aileron is deflected. This

gives a slightly lower

roll rate near neutral but

seals the ailerons for max

effectiveness as full

deflection is neared. It's

like having on-demand

power steering.

Curtis

also used Super Stinker

technology on the new

wings he designed for

Aviat's newly certified

follow-on to the S-2B, the

S-2C, and the difference

really shows in that

airplane. The new wings

and Ed Saurenman-designed

tail give the S-2C

completely different, and

much better, handling than

the earlier airplane.

Out in

the practice area with the

-11B, the first thing I

did was play with the

ailerons, which is another

way of saying I played

with tumbling my own

gyros, it goes around so

fast. Aviat says the roll

rate is somewhere around

400°/sec, give or take a

little. From my

perspective, as the

horizon was ripping

around, all I can say is

that at max deflection it

is at the upper limits of

my own ability to see

what's happening. The

horizon seemed to be

coming around to level

just about the time I

thought I'd actually

gotten the aileron against

the stop.

The

airplane is dead neutral

on every axis, so you

don't leave it unattended

for long periods of time.

Duck your head to study a

chart for too long and

you'll find yourself

pointed somewhere else

when you bring your head

back up.

The airplane's aerobatic

capabilities are so far

beyond my own that it made

my feeble efforts

seem...well...effortless.

The inside-outside

pressures aren't perfectly

balanced, but are so close

that when doing rolling

360° turns, hitting the

points was no sweat and I

wasn't conscious of having

to fight pressures while

pushing the stick forward.

Outside loops, from either

top or bottom seemed to

happen almost

automatically because it

clawed its way up the

backside so easily. Its

vertical maneuvers seemed

especially easy. Doing

vertical rolls has never

been one of my strong

suites, but it seemed to

settle into an up line and

give me all day to get it

right before going for the

ailerons. I'm always

amazed when I get two

vertical rolls out of

anything, but here it was

child's play. Three was

just as easy and I was

going in at only a little

over 200 mph and could

easily fly away at the

top.

The

snaps took a little while

to figure out because it

has so much aileron. It

rolls so fast, its hard to

tell which is snap and

which is aileron in the

roll. I was going to try

some without aileron, but

got side tracked.

The most impressive part

of the airplane (other

than its willingness to

keep going up hill) was

the absolute lack of any

kind of rolling inertia.

It starts and stops rolls

instantly. Instantly!

Point rolls in any

direction, up, down or

anywhere in-between, are

so easy they should be

illegal.

I found

the semi-supine seating to

be interesting but I

didn't know how

interesting until I got

back on the ground. The

airplane has one of those

new fangled digital,

electronic "G" meters and

I couldn't tell how much

"G" I was actually pulling

because the meter was in

recording mode or

something. I was using

pulls and pushes that felt

more or less normal to me

and was absolutely no more

aggressive than usual

because I have a bad habit

of making myself sick. So,

I was just flying to my

usual limit. Later, when

Lou checked the "G" meter,

I had put 8 positive and

5.1 negative on it. That

really surprised me. At no

time did I feel as if I

was working the airplane

that hard because my body

wasn't feeling it.

Coming

back into the pattern, I

initially had to work to

get the speed down to an

acceptable pattern speed.

This meant pulling back to

about 14" of manifold

pressure which was still

about 130-140 mph. It

wasn't until the throttle

was practically closed

that speeds came down to

110-120 mph where I wanted

them.

On my

initial landing, even

though I was in as close

as I would be for a normal

Pitts, power-off landing,

it became immediately

apparent, power-off with

that big prop out there

wasn't going to work. The

second the power was

against the stop, the

airplane decelerated and

pushed me forward in the

seat and the ground

started up immediately.

With

just a touch of power, the

airplane rode through a

turning approach as though

it was on rails. I used

110 mph initially with 100

mph over the fence. As I

intersected centreline and

rolled wings level, I

slowly killed the power.

The airplane settled into

a three point position for

a few seconds then

dribbled onto the ground

with a firm series of

clunks and a slight scream

from the tiny tailwheel

bearing.

Out of

three or four tries, all

but one saw me kissing

gently off the mains and

getting a little

hippity-hop. Fortunately,

the spring gear is nice

and stiff so I had no

problem telling what the

airplane was trying to do.

The airplane was amazingly

well behaved, especially

considering I was working

with an 8 knot, quartering

tailwind which always

makes tailwheel airplanes

do quirky things on

landing. Naturally, as

soon as I quit, the tower

changed runways.

The

first touch and go was

really a hoot and will

stick in my mind for a

long time. I was working

on ironing out the hippity

hop and, without thinking,

briskly moved the throttle

to the stop for the go

part of a touch and go.

Instantly the airplane

slapped me on the back

side and was in the air.

Instantly! I knew a 152

was somewhere ahead of me,

also in a touch and go, so

I slid to the right where

I could see him. I was

trying to keep the nose up

so I wouldn't catch him,

but I'd forgotten the

throttle was still against

the stop and all of Monte

Barrett's pumped up ponies

were still roaring at full

bore. I caught sight of

the 152 quickly growing

bigger to the left of my

nose and I was already

well above him. I

hurriedly asked the tower

for an early crosswind and

ripped into a tight turn

across behind the 152 as

soon as they rogered. I

glanced at the altimeter

as I came behind the

Cessna: Pattern altitude

is 1,000 feet and I was

already at 1,500 feet

barely half way down the

runway. Rock and Roll!!

At the

Aviat Fly-in at the

factory in Afton, Wyoming

in October of last year

(this year it's the second

weekend in September),

several pilots evaluated

the 11B and all were

impressed. That however

was at 6,000 MSL altitude.

They ought to try it down

here. At 1,500 ft MSL it

is an amazing airplane.

Even

though most of the talk

about the airplane centres

on its aerobatic

capabilities, I keep

coming back to its

possibilities for the

average sport pilot.

Especially those on a

budget. It would cost

little more to build this

airplane than any other

single place biplane and

less than almost any

composite kit. Although a

two-blade Hartzell prop

would raise the costs over

other projects with fixed

pitch props, that would be

partially offset by the

lower cost of the

six-cylinder core.

For

those builders in a hurry,

the components offered by

Aviat Aircraft are all in

finished form. The

fuselage is finish-welded,

epoxy coated and ready for

installing systems. The

same is true of all other

welded components. The

wings are assembled and

ready for cover. Aviat

Aircraft, however, wants

to make it clear, they are

only making these specific

components, not kits.

As

homebuilt airplanes go,

the S-1-11B/Super Stinker

is low-demand in the

building department and,

once the thrill factor is

overcome, only slightly

more demanding than a

Citabria to takeoff and

land. However, it would be

absolutely imperative for

those who have no time in

something with a lot of

power and light controls

to get some dual

instruction in a two-place

Pitts before attempting a

first flight. All the

Champ or Cub time in the

world isn't going to help.

The

S-1-11B is a comfortable

airplane and cruises at

anything you want

depending on the amount of

fuel you want to burn.

It's hard to get it much

below 150-160 mph in

cruise at any logical

power setting and Lou

Meyer says he flight plans

190 mph (165 knots) at

21-22" which is down

around 55% power. It holds

35 gallons, so, with a

"normal" 250 hp, O-540

burning 13 gph, or less,

at normal, not reduced,

power settings, you've got

a solid 2.7 hours of fuel.

Aviat

Aircraft is still offering

plans for the old Pitts

standard, the S-1S, which

is a huge amount of

airplane for those wanting

performance on four

cylinders. However, for

those wanting the absolute

ultimate in homebuilt

amazement, the S-1-11B is

going to be hard to beat.

Of course, it's a Pitts.

So what else did you

expect?

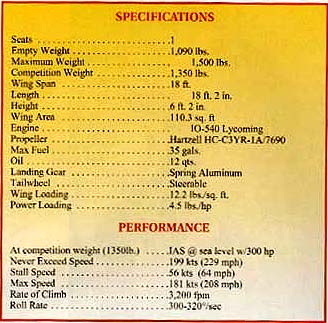

SPECIFICATIONS

Seats 1

Empty Weight 1090 lbs

Maximum Weight 1500

Competition Weight

1350

Wing Span 18 ft

Length 18 ft. 2 inch.

Height 6 ft. 2 inch.

Wing Area 110.3 Sq. Ft

Engine IO-540 Lycoming

Propeller Hartzell

HC-C3YR-1A/7690

Max Fuel 35 Gal

Oil 12 qt.

Landing Gear Spring

Aluminium

Tailwheel Steerable

Wing Loading 12.2

lbs/sq. ft.

Power Loading 4.5

lbs/hp

Performance

At competition weight

(1350lb.)IAS @ sea

level w/300 hp

Never Exceed Speed 199

kts (229 mph)

Stall Speed 56 kts (64

mph)

Max Speed 181 kts (208

mph)

Rate of Climb 4,000

fpm

Roll Rate 400°/sec