Another reason the airplanes

aren't seen often is that we are

only now coming to the end of

the traditional three year

gestation period that begins

when the first kits of a new

design are delivered. Last year

there were no Rebels at Oshkosh.

This year there were seven.

Murphy expects as many as 100

may fly this year, so Oshkosh

could easily see the Rebel crowd

bursting at the seams next year.

Structurally,

the airplane is interesting for

a couple of reasons. In the

first place, it is a

professionally designed and

engineered unit. Second, it is

all aluminium and third, Murphy

has incorporated state of the

art CNC technology to make the

kits super easy to assemble.

Darryl Murphy

teamed up with ex-deHavilland

head of engineering Dick

Hiskocks when he decided to

build his idea of a bush bird.

Hiskocks was part of the

original design team on the

Beaver and a lot of that design

philosophy shows in the Rebel.

For one thing the fat 4415 wing

utilizes three spars and a bunch

of stringers for stiffness. On

top of that the fuel is kept in

wet sections of the wing and is

easily expandable from the basic

25 gallons to a whopping,

bladder busting 50 gallons for

those serious about staying up

there a while.

The fuselage

is a rounded box most notable

for its width, 44 inches across

the shoulders, which puts it in

C-182 category and 7 inches

wider than a C-152. It is the

width of the cockpit combined

with the small size of the

airplane that gives it a

deceivingly boxy look. It is

visually wide for its length.

The anti-canning creases seen on

the sides of the fuselage

replace the stiffeners of the

original design and save nearly

four pounds while eliminating a

bunch of parts and rivets.

And speaking

of rivets, that is one of many

areas where Murphy has worked

hard to reduce building time.

The airplane is specifically

designed around the Avdell Avex

blind rivet. Although appearing

to be of the common pop rivet

(actually a brand name) design,

the Avdels are universally

accepted in Europe and are

considered aircraft quality.

Although the mandrel is not

mechanically locked in place

like a Cherry or Huck MLS, their

aluminium shell is designed to

retain the mandrel as long as

practical. Because the aircraft

design takes into account their

lower strength (167 pounds in

shear versus 357 pounds for an

AN 4 in similar skin) there are

lots of rivets to be pulled,

nearly 20,000.

The real

beauty of the pulled rivet in

this application is that it

works with the Murphy's

pre-punched components to

eliminate the need for

traditional jigging. Other than

a 16 foot table that has to be

perfectly flat to act as a

datum, nothing needs to be

constructed other than the

airplane itself. Lots of

aluminium designs demand a

sizable time investment in jig

construction to ensure a

straight airplane. The Rebel,

however, depends on the flat

table and the accuracy of

factory-punched pilot holes to

jig the assemblies.

As the kit is

delivered, the skins have all

holes punched via CNC machines.

There is no bending of any

components to be done and

matching tooling holes are

located in individual pieces to

aid in positioning the skins.

The builder draws centrelines on

internal components such as

ribs, the centrelines are

positioned in the pre-punched

holes of the skins, and matching

holes drilled to size.

When

this type of tooling is combined

with the blind rivet, it is easy

to see why so many Rebels are

under construction and why so

many are about to be finished.

The skill levels usually

associated with jig construction

and traditional riveting are no

longer necessary. The learning

curve for this type of

construction would be almost

non-existent.

When

this type of tooling is combined

with the blind rivet, it is easy

to see why so many Rebels are

under construction and why so

many are about to be finished.

The skill levels usually

associated with jig construction

and traditional riveting are no

longer necessary. The learning

curve for this type of

construction would be almost

non-existent.

A builder

could, if desired, use bucked AN

rivets in place of the Avdels,

although the airplane would have

many more rivets than necessary

in that case. Also, there exists

the probability that AN 3

rivets, rather than -4s, could

be used in place of the 1/8"

Avdels because of the strength

is there and the weight would be

less. This is subject to final

engineering verification and

would undoubtedly increase

building time substantially

because the Avdels are so quick

to install.

Originally,

the Rebel had a "V" type bungee

gear but on the later kits they

ahve gone to an aluminum Wittman

type gear. This combined with

the sleeker cowl for the 160

engine upped the speed of the

airplane to a solid 125 mph in

cruise. More important,

according to factory test pilot

Rob Dyck (Jack, this is correct

spelling), it greatly improved

the airplane's ease of landing

and it rides rough fields much

more smoothly.

The airplane

is shipped in three basic kits,

the empennage ($xxx), the wing

($xxx) and the fuselage ($xxx).

If bought all at one time,. the

cost (fall 1994) would be $xxx.

The airplane

is approved for four engines and

the gross weight is changed

changed to match the engine. The

66 hp Rotax 582 is stickered at

1057 pounds (Canadian ultralight),

the Rotax 912 at 1450 lbs, the

0-235 Lycoming at 1650 pounds

and the 0-320 at XXXX pounds.

According to those at the

factory who have been keeping

track of customer's airplanes, a

912 airplane should empty at

about 600 and the 115 hp

Lycoming birds in the 825-875

pound range. The 160 hp version

they had at Oshkosh emptied at

950.

We poked

around in a builder's manual

and, although its hard to say

how good a manual is until you

actually try to use it, it

looked to be not only complete

but detailed in a very

commonsense sort of way. For

instance, in the tools required

to build each component they

listed a felt marker. One entire

step was spent waiting for the

epoxy chromate primer (supplied)

to dry because, if left tacky,

it would later catch and trap

drill filings. Nice touch!

Incidentally,

the way the parts are prepared

and the way the manual reads

instils confidence. This is not

always the case. Reading some

manuals leaves you overwhelmed.

My feeling after reading this

one was, "...even I could build

this airplane..."

Whether their

estimates of 500-600 hours to

build the basic airframe is

correct or not is hard to

verify, but given the methods

used in construction, the time

estimates may just be right.

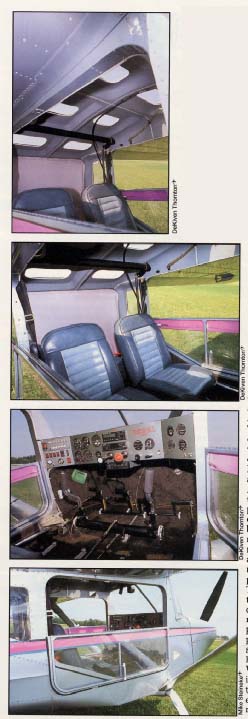

I knew

absolutely none of the above,

when I scrambled into the

cockpit at the end of Runway 36

at Oshkosh. All I knew as I

scrambled into the right seat

was this was one of the very few

homebuilt aircraft I had boarded

that had seats adjusted via

Cessna type rails rather than

the stack-a-cushion system.

The door

latch, like so many parts of the

airplane was simple and to the

point: a spring loaded dog stuck

out the back edge and was

retracted by pulling on the

cable running through the middle

of the door. Very positive. Very

simple. Very light.

Settling back

in the seat and trying to orient

myself I noticed I felt I was a

long way back in the cockpit.

Rob Dyck explained from the left

seat that was the result of the

160 hp installation. They moved

the firewall back three inches

and the pilots almost twice that

amount. The result is the front

door pillars appear further

forward than normal and the

overhead cuts off some upward

vision. Even Rob said they

needed to open up the skylights

further. The headliner is a

pre-moulded piece that looked to

have plenty of room to install

bigger skylights which would do

wonders in opening up the

feeling of the cockpit and

increasing upward visibility.

Personally, I'd open up the

entire panel behind the main

carry-through back to the

stringer over the pilot's head.

If it needed more structure to

do that, it would be a

worthwhile investment.

What the

cockpit lacked in light, it more

than made up for in room. It was

much, much wider than it looked

from the outside. Further, as I

glanced around inside, I noticed

the third seat in back and asked

Rob about it. They designed the

airplane to handle 200 pounds in

the back seat and the real

fuselage has a floor so it can

be used as a camper. Rob said he

stretched out back there and

slept all the way back from a

fly-in while the other two kept

their eyes open.

It wasn't

until the airplane was running

that I noticed I had no brakes

on my side. Normally, not a big

deal, but as soon as I started

the turn onto the taxiway I

could tell the tailwheel springs

were too soft to get any

immediate response out of the

tailwheel. At a couple of points

i had to ask for some brake just

to make it around the corner.

Running the

MAC electric trim indicator into

the green, I kept an eye on the

flagperson standing at the edge

of the runway and immediately

powered up onto the centerline

at her request.

On the

runway, It was clear the

airplane had good visibility

over the nose. I couldn't see

straight ahead without

stretching just a little, but

the edges were clearly visible,

although the door pillar was

slightly in the way.

Cleared to

go, the throttle was gently

pushed forward, but from the way

the airplane reacted, you'd have

thought I hammered the throttle.

For what looked to be a normal

high wing airplane, this thing

rapidly assumed the personality

of a boxy bullet. As the

throttle found the panel I eased

the tail up and gently played

with the rudders. They were

effective, but the airplane

didn't really need much from me

to stay straight. More or less

straight anyway.

The tail was

barely off the ground when the

airplane launched and I ran into

the aforementioned climb

problem. There was no doubt in

my mind I could easily have had

3,000 feet at the other end of

the runway, the way that thing

was going up hill. Rob said it

was about 1,200 fpm, but at

70-75 mph that gave a deck angle

that approached ridiculous.

Without thinking, I throttled

back, as I pushed the nose over,

because my gut told me anything

with that kind of takeoff and

climb performance was going to

put its nose down and start

really hauling and I didn't want

that much speed in the pattern.

My gut was

wrong. With a 15% airfoil, it

wasn't about to accelerate

through Mach. It hit a drag wall

and hung in there at about 125

mph while I stuck my face in the

windshield looking around the

wing root for all the traffic I

knew was out there.

Once over the

lake, I let the nose up and we

went upstairs in a hurry.

We levelled

out and I started playing. As I

did Rob reached up to the

overhead lever and put the flaps

into a 6 degree reflexed

position which he says tacks a

few knots onto cruise.

I rammed some

aileron into it without rudder

to see how much adverse yaw it

had and was surprised to find it

had very little. I had expected

those Hershy bar wings to

require lots of correcting

rudder but they didn't. The

rudder was plenty effective, but

very little was needed for

coordination.

The ailerons

themselves are Cessna-normal.

Nothing out of the ordinary with

Spam can roll rates. In other

words, it doesn't have a quicker

than normal feel that many

homebuilts exhibit. Later,

during stalls with the ailerons

drooped, the roll response fell

off because of the drooping,

which is one of the reasons they

limit it to 18 degrees. Other

than the change with flaperons

out, the controls on all axis

will feel very familiar to

anyone flying the airplane

because they are right in the

middle of the profile. They feel

a little like every airplane but

exactly like none

With enough

altitude under us, I brought the

power back and crept up (or is

it down?) on a stall. Somewhere

around 45 mph it started

buffeting and the rate of

descent went up a few hundred

fpm and the stick was against

the stop. The flaperons made

very little difference in the

nose attitude or speed bleed-off

but they did knock at least four

mph off the stall. When totally

stalled and clean the ailerons

and rudder worked nicely and

easily controlled the airplane.

With the flaperons out, the

control was noticeably softer.

Given time I would have liked to

mess with very slow speed turns

or turning stalls and see if

large aileron inputs in those

situations would stall the

inside wing. Rob says they've

looked at that but haven't found

it to be a problem. Still, it

would be fun to investigate it.

I poked and

prodded the airplane and found

the only thing I actually didn't

like about it was the visibility

and the general "dark" feeling

of the cockpit. A lot of older

airplanes (Pacer, Maul, Chief,

etc) are that way, but the Rebel

doesn't need to be. Larger

skylights would make a big

difference. Past that, there

isn't much that could be

changed.

We threaded

our way through traffic back to

Oshkosh and I did my best to get

the airplane slowed down to the

65 mph Rob wanted on final.

Unfortunately, we were forced

into flying a bastardized wide,

fast approach and I never really

had a chance to get it trimmed

up on speed.

That however

was no excuse for the lousy

landing I made.

I'm here to

tell you the spring gear on the

airplane really works well. Even

though I touched down harder

than necessary with a little

drift to the left, the airplane

didn't hop, jump or try to bite

either its own tail or mine.

After touchdown I did, however,

find I would have given anything

for a set of brakes or much

tighter tailwheel springs.

Between the two of us, Rob and I

put on quite a show. If I had

done a better job on short final

all the gyrations wouldn't have

been necessary, since even

though I gave it every

opportunity, it never did

anything particularly spooky.

Just embarrassing.

The ground

handling, had I done my part and

had the tailwheel been a little

more responsive, was actually

not much more difficult than a

Citabria. I think!. The

forgoing, the pilot and the

tailwheel springs, made it

appear more difficult than it

was.

During the

entire approach at no time did

the nose get in the way. It

wasn't until just before

touchdown (such as it was) I was

even aware the nose was out

there.

The Murphy

Rebel and its apparent success

says something really important

about sport aviation and the

markets it represents. At the

very least it says there is a

market out there for a really

usable airplane that has a

little character all its own. It

says there are a lot of people

who want airplanes that are

practical in the ways they

personally define that word.

They don't need 200 mph or

aerobatics or any of the other

flash and glitz that is so much

a part of some designs. They

aren't looking for Shelby

Cobras, they are looking for

four-door Chevies they can drive

and drive and drive. That's the

Murphy Rebel. Its an airplane

for the masses. Its an airplane

to be used, not simply owned.

Maybe that's

why its named the Rebel. It is

going against the current trend,

marching to its own

four-cylinder dummer and all

that.

The Rebel is

a usable airplane and that's

saying a lot.