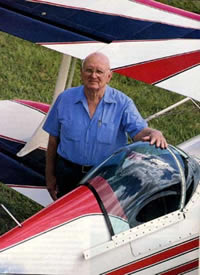

The Old Master Does it

Again

Help me find an analogy

here! How about, Van Gogh

decides to paint another

picture? Or maybe, Michael

Angelo whittles up one

more block of marble? How

about Bach (Johann, not

Richard) pens another

little ditty?

They

all apply in this case

because an old master is

an old master, whether the

medium is paint, marble or

music. Or aerobatic

airplanes. In that field

there is only one

recognized old master,

Curtis Pitts. And he has

done it again. In spades!

After a hiatus of over two

decades he has just given

us another master piece.

He calls it Super Stinker.

I

returned from Curtis's

place in Homestead,

Florida at 0100 hours this

morning and I can honestly

say I don't remember the

last time an airplane kept

me awake. At 0300 hours I

was laying in bed staring

at the ceiling, while my

mind's eye watched that

long nose whip around a

totally blurred horizon,

or hang effortlessly from

an invisible moon, while I

waited for it to get slow

enough to hammerhead.

I also

don't remember the last

time I wanted to own an

airplane as badly as I

wanted to own that one.

Actually, I do too

remember. It was after

flying the prototype S-2

Pitts.

Even in

a field like sport

aviation, where it seems a

new generation of pilots

pops up every three years

who know nothing of what

has gone before, there are

certain standards of

performance. In aerobatic

airplanes, that standard

is, and always has been,

the Pitts Special. Even

the newest, greenest

convert to sport aviation

knows that. Yes, in the

unlimited arena, the

leaders are now flying

hot-rod monoplanes, but

everywhere else, sportsman

to advanced, the little

Pitts Special still reigns

supreme.

The

actual leader in the

unlimited category is

money. A new unlimited

mount that will let you

butt heads with the top

dogs starts at $150,000

and quickly works its way

up to nearly $250,000.

Homebuilders need not

apply. Money is the

primary language spoken

here!

That's

one of the reason's Curtis

says he decided to dust

off his drafting board and

do it again. He wanted to

design an unlimited

category airplane the

average homebuilder could

screw together that, when

combined with lots of

talent and even more

practice, would let

him/her move within sight

of those at the very top.

At this juncture, before

everyone whips out their

check book and hunts up

Curtis's address, we

should mention that he

hasn't made up his mind

what he's going to do with

Super Stinker. As this was

being written, he stated

he would very much like to

get back into the airplane

building business and

offer plans, but was very

leery of the liability

problem. He wanted to

enjoy aviation, not wait

for the next subpoena, so

he wasn't certain he was

going to make plans

available for the airplane

or not. He said he'd make

up his mind after Sun 'n

Fun, so, by the time you

read this, we should have

an answer.

Super

Stinker is the last in a

long and distinguished

line of excitable,

three-dimensional skunks.

It started with the

original S-1 Pitts, the

best known of which was

Betty Skelton's 'Lil

Stinker. The S-1's birth

date was 1945. Then there

was the first certified

unlimited aerobatic

biplane, the S-2. The

prototype was named Big

Stinker and it went into

serial production as the

S-2A with a 200 hp

Lycoming and constant

speed prop in 1971. Now,

23 years later, Curtis,

with the help of some of

the same friends that

helped forge the Pitts

Special into the aerobatic

weapon it is, now has an

entirely new airplane

flying.

And you

can take it from us, Super

Stinker is some kind of

hoss.

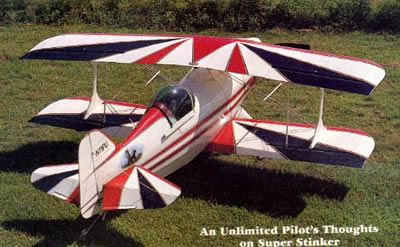

From

the outside it would be

easy to say Super Stinker,

officially known in

Pittsdom as the Model

11-260, is nothing but a

scaled up S-1S with a 260

hp Aztec engine bolted to

the front. Or is it a

scaled down S-2B with the

front pit removed?

Actually, it is none of

the above. It is an

entirely new airplane and

it takes only a casual

perusal of the airframe to

see that. Starting with a

clean sheet of paper,

Curtis did a complete

finite-element analysis

aimed at letting the

airplane safely survive

the unlimited aerobatic

category, where "G" limits

are routinely ignored. His

goals were strength and

light weight coupled with

several new innovations

aimed at making the

biplane competitive in a

monoplane world. This

included a new symmetrical

aileron design, hinged

well back, to give the

roll performance all the

new akro birds feature.

In

terms of size it is closer

to the single-hole

airplanes than the two

seaters. The upper span is

18 ft, which makes the

span less than a foot

longer than the S-1S/T

series, but two feet

shorter than the two-holers.

The fuselage length is

where the difference is

most noticeable. It is

nearly two feet longer

than the little airplanes

and just a foot shorter

than the big ones.

The

long, long nose puts the

IO-540 well ahead of the

firewall, so there is

plenty of room behind it

for any of the accessory

variations seen with the

different models of that

engine. With the heavier

engine that far ahead, it

stands to reason the pilot

would have be well behind.

And he is. The resulting

fuselage lines completely

eliminate the stubby,

pot-bellied bumble bee

appearance so associated

with Pitts Specials. It's

a long, lanky dude and is

pretty darned sexy

looking.

There

is another subtle

difference that is most

noticeable, when your feet

work their way down under

the panel, as your butt

heads for the seat: You

don't feel as if you're

disappearing into an open

manhole because the

fuselage isn't nearly as

deep as earlier airplanes.

In fact, the cockpit is

several inches wider and

longer, which makes for a

decidedly non-Pitts

feeling to the flight

deck. It is larger, very

airy and cheerful feeling

and fits exactly,

precisely the way it

should.

To a

Pitts aficionado, its

unnecessary to point out

the decidedly non-Pitts

wingtip and tail shapes.

The wingtips are shaped

the way they are to allow

the ailerons to run as far

out as possible for

maximum effectiveness. The

tail surfaces are angular,

rather than being the

gracefully rounded shapes

associated with Pitts

Specials. This is because,

as Curtis put it, he

didn't want to make the

folks now building the

certified Pitts Specials

mad.

Come on

Curtis, it needs a Pitts

tail! Go for it! We'll

protect you.

The

spring gear, is another

departure for a Pitts

biplane, although the

first S-2S models had it,

but couldn't get certified

because they wouldn't pass

the drop tests. Most of

the serious competitors

now flying Pitts have

converted their airplanes

to spring gear for the

lower drag. Curtis did the

same on this one, for the

same reason.

Most of

Super Stinker's gestation

period was conducted in

secret. Few knew the Pitts

skunkworks (now there is

an apropos term) was about

to give birth to another

Stinker. Curtis, as

everyone who knows him

would agree, is very much

a do it first and talk

about it later type of

person. He doesn't believe

in hype. So there weren't

any signal flares sent up

letting the rest of sport

aviation know what he was

up to. Actually, Super

Stinker would have been

here earlier but Hurricane

Andrew blew most of Pitt's

shop facilities into

Georgia and pretty well

scrambled his life for a

while. First things first.

The old tin hangars on the

tiny grass runway which

had been home to several

generations of Pitts

Specials, practically

disappeared in the

hurricane. However, with

the help of a lot of

friends, they were

replaced with much more

substantial concrete

structures. The concrete

wasn't even dry and piles

of soaked plans and

memorabilia still littered

the remaining office

space, when progress of

Super Stinker began anew.

Now

it's finished and flying.

And what is most

astounding to me,

personally, is that I was

given the opportunity to

fly it. It was one of the

most flattering, and, as

it turned out, most

exciting opportunities of

my life.

Curtis

has a hard act to

follow...himself. He not

only has designed an

airplane that is supposed

to do akro combat against

foreign airplanes using

the best in space-age

technology, but he has to

follow in his own

footsteps. His new

airplane is undoubtedly

going to be judged against

everything he has ever

done and it had to be more

than just a good aerobatic

airplane. It had to be the

next logical step upward

in the Pitts Special

legacy. Having a pilot

say, "...it's good,

but..." wouldn't cut it.

In unlimited competition,

there is no room for

"buts." It either is or

isn't right.

All of

that was going through my

mind, as I stepped over

the side and slid down

into that relatively wide,

comfy seat. I wanted

desperately for Curtis to

hit another homerun. But,

I wouldn't lie to myself.

And I wouldn't lie to him.

The chips were going to

fall where they may.

As I

was strapping in, I had

absolutely no feeling that

I was strapping in to a

Pitts. Not even a new one.

The way the seat sits

almost flat on the floor

and the way the sheet

metal stopped well down on

my shoulders created a

cockpit feeling that had

practically nothing in

common with any Pitts

going before it. The

instrument panel wasn't in

my face and my legs were

actually stretched a

little further forward

than I wanted. Although

the cockpit fit me like a

glove, I in no way felt

shoehorned into it or

crowded. I can't imagine

any pilot being too big to

fit. Since the rudder

pedals are adjustable, I

also can't imagine a pilot

being too little. Curtis

has learned a lot about

cockpit design in the past

few years and it shows.

The

closest comparison to any

other Pitts, in the way

the cockpit feels might be

the single place S-2S.

But, Super Stinker has

better visibility.

The

nose that looks long from

the outside, stretches on

forever from the inside.

It, however, isn't a

factor of any kind. Sure,

you can't see squat

straight ahead, but

visibility out to the

sides is much better than

something like an S-2A. In

actuality, it is much

better than most of the

unlimited birds, including

the Extra and Sukhois. It

is also better than the

One Design because it is

so narrow, in comparison.

With the nose out there

like a magic wand, the

pilot would have to be

blind not to know what the

airplane was doing. Or

about to do.

The cockpit is

rudimentary, although the

centre stack of radios was

an interesting addition.

Not a lot of biplanes are

so equipped and

practically no Pitts are.

However, with the panel

the size it is, nothing

was crowded.

Before

I jumped on a smoker and

headed for Homestead,

Curtis had primed me over

the phone with all sort of

little forewarnings;

"...rolls faster than

anything I've ever

designed...You won't like

the ailerons, they are so

light....not an airplane

for a casual pilot..."

Then, after I got there, I

heard some of the same

things from his partners

in building the airplane,

Pat Ledford, Bill

Lancaster and Don Lovern.

Pat, in case you don't

recognize the name is the

guy who worked hardest on

Curtis to put out plans

for the single place in

1959-60. He built the

first plans-built single

place with Curtis doing

the drawings while Pat was

building the airplane. The

same group is still

cranking out airplanes

together.

By the

time the mag switch was

twisted and the engine

started to crank,

adrenaline was pooling in

my cowboy boots. I may not

have been spooked, but I

was certainly "attentive."

It's

not hard to tell, when

you've fire up a six,

rather than a four

cylinder Lycoming. The

bark is still there, but

the smoothness is hard to

miss. It was also hard to

miss the fact I was going

to have problems with the

brakes.

I

should have adjusted the

pedals in closer, because,

when I went for the brakes

my boots just slid up the

pedal rather than mashing

it down. Normally, this

wouldn't have been a big

deal, but the airplane had

a locking Haigh tailwheel

on it, so, when I was in

close quarters and the

tailwheel was unlocked,

brakes were all I had to

steer the airplane.

I

rolled about 100 feet,

felt like I was out of

control of the situation

and braked to a jerky

halt, summoning Pat over

as I did. Sliding the

canopy back, I handed him

my boots and socks and

trundled merrily on my way

barefooted, with my toes

wrapped over the brake

pedals.

Everyone has their own

feelings about it, but,

I'd put a regular

steerable tailwheel on the

airplane. On the other

hand, the Haigh certainly

takes a lot of sweat out

of landing. The tailwheel

lock was hooked to the

stick like a late model

T-6 or P-51: If the stick

was anywhere except full

forward, the tailwheel was

locked straight ahead. It

was a neat arrangement.

With better shoes, I later

found most of my steering

problems went away.

As I

rolled onto the centerline

and sucked the stick into

my lap, I couldn't help

but grin a little.

Actually, I was grinning a

lot. The Lycoming was

barking away up front and

the edges of the 75' wide

runway were clearly

visible. The nose blocked

everything ahead and the

prop disk looked like it

went most of the way out

to the inter-plane struts.

This was going to be fun!

My left

hand started inching

forward smoothly. I was

being conservative because

I had no idea what the

airplane was going to do

once 260 horses started

trying to drag its 1100

pound airframe forward.

But, the airplane

obviously didn't want to

be conservative. It was

impatient and wanted to

get with the program. And

so did I.

The

airplane hadn't rolled two

hundred feet and the

throttle wasn't half way

forward, when I felt like

I was home! This airplane

wasn't going to do

anything stupid! At least

not anything I didn't ask

it to do. So, I pushed the

throttle to the stop and

felt the nerve ends in my

butt light up as the

airplane slapped hard

against them.

Tail

up, I stared straight

ahead at the nose and the

bright blue sky beyond. I

was letting my peripheral

vision keep track of both

sides of the runway at one

time and signal my feet

what was needed. Other

than an occasional rudder

pressure to the right, the

airplane didn't ask for

anything, as I kept

pressuring the stick back

in an effort to hold the

slightly tail down

attitude I wanted.

In much

less time than it takes to

talk about it, the

airplane was off the

ground. I had nothing to

do with it. It just

launched itself, as the

Lycoming yanked me through

the proper mixture of

speed and angle of attack.

The acceleration had

unlocked the valves on my

adrenaline pumps and I was

in the process of getting

an adrenaline high. But,

nothing was scaring me.

Nothing was even bordering

on being out of the

ordinary, it all fit

together so well. It was

all so, so smooth.

As I

left the ground all of the

comments about the aileron

sensitivity were replaying

themselves in my mind, so

everything I had learned

in every takeoff I had

ever made crowded itself

into that portion of my

mind which controlled the

stick. But it was

unnecessary. The airplane

was a bullet, a totally

stable bullet that was

cleaving a jagged hole

through the slightly humid

Florida air and needed no

help from me.

Every

nerve I had was sensing

the control stick and the

changing pressures, ready

to yell at me to calm down

and use less pressure, or

less movement. But, this

too was over-kill. The

S-Stinker and I bashed

through a few bits of

turbulence, which gave me

a golden opportunity to

over control. But, it just

wasn't there. The airplane

immediately told me that

if I moved, it would move.

But, if I didn't do

anything, it wouldn't

either. We were totally

connected.

As the far end of the

3,000 foot runway flashed

under me, the nose at a

ridiculous angle, I

glanced at the airspeed.

140 mph and the altimeter

was winding up like a

clock! Best rate was

around 100 mph, but

pulling the nose as high

as I could, I never got

the needle below 110. And

we kept going up. And up.

I

wasn't even out of the

pattern and I was

seriously in love. This

wasn't just another

airplane and I could

already tell it. If I

didn't do a single roll or

loop, just what I had

already sampled on the

takeoff told me Curtis had

once again worked his

magic.

As I

levelled off at 4,000

feet, I made a couple of

quick turns and confirmed

it: Super Stinker had that

unique Pitts feel to it.

It is an intangible feel,

but one that is very

definitely identifiable.

Those who have flown both

Eagles and S-2As, always

comment on a subtle

difference between the two

seemingly identical

airplanes. The Pitts has a

softly "dense" feel to it,

a term coined by test

pilot Carl Pascarell to

describe the feel. It goes

past feeling solid, to

some sort of difficult to

define control feel that

makes the pilot think the

airplane is pushing

against something solid

every time it moves. It

doesn't make any

difference whether it is

in normal flying or hard

aerobatics, the airplane

does everything in an

authoritative way that

greatly reduces the

demands on the pilot to

keep his flying crisp.

Take

the way the airplane does

point rolls for instance:

In most ultra-hot

aerobatic airplanes the

first few times a pilot

tries point rolls, he'll

hit the points but there

will be a little bobble as

he works to figure out the

ailerons to hold the

point. Not so the Super

Stinker. My first point

rolls were on the backside

of a Cuban-8. I did a four

point on the first half

and they were so clean and

easy, I did a roll and a

half with 8 points on the

second half.

The

important thing here is

the point rolls were as

clean and on target as I

have ever done and I had

less than 10 minutes in

the airplane. Don't read

this as me being a great

pilot because I'm not. In

the same situation with

the One Design, Extras,

etc., I would have been

embarrassed to have anyone

see my point rolls. But in

the Super Stinker, I would

have been ready to have

them judged right then and

there, they felt that

good. The ailerons and the

way the airplane behaves

in rolling manoeuvres are

absolutely the best I've

ever seen. The touch of

The Master was showing

through again.

Just

about the first thing I

did was diddle around with

the roll rate. And boy

does it have a roll rate!

When I finally figured out

how much rudder it needed,

I was actually seeing

something approaching

visual gray-out just

because the horizon was

such a blur and it

happened so fast. Only a

week earlier I had been

doing the same thing in

the One Design, which

designer Dan Rihn says

they estimate at something

over 400 degrees a second.

If that's right, the Super

Stinker is doing at least

that.

As fast

as it rolls, however, that

same dense feeling works

into it. The roll rate

isn't noticeable until the

ailerons are hammered

fairly hard. The break-out

pressures are actually

quite a bit higher than

they initially feel like,

but the ailerons

themselves are quite

light. The net result is

that there is absolutely

none of the balanced on

the head of a pin feeling.

The airplane feels much

larger and more stable

than it has a right too.

There

is no toy-airplane feel as

there is with so many

airplanes this size.

And

then there are the snap

rolls. Another surprise. A

Pitts normally takes a

little technique to get it

started clean and even

more technique to stop it

clean. Not the Super

Stinker. Just a little

tweak on the stick, a

stomp on the rudder and

the world disappears for a

second or so. A gentle rap

of forward and opposite

and the airplane stops on

a dime with nine cents

change. By the third snap,

it telegraphed how it

wanted to be snapped and I

obliged. Another half hour

snapping and I'd let those

be judged.

One

thing I have always been

lousy at are vertical

rolls. Even in my own

airplane I'm not worth a

damned. So, I was a little

nervous as I sucked up

into vertical with The

'Stinker. I thought I'd

try a half roll first and

see how it went. Bam! It

was nearly flawless, as

near as I could tell. The

hammerhead after the roll

was super sloppy, but the

roll was good. Then a full

one. Again, the wingtip

tracked right around and

stopped where I wanted.

Amazing! The airplane was

just too good to be true.

At one

point, I was slow (an

unusual situation in this

airplane), so I closed the

throttle and stomped full

left rudder. It obliged me

with a spin to the left. I

watched it through three

turns waiting for the nose

to go the rest of the way

down, but it never did. It

looked to be much further

off the vertical than most

Pitts. But, when I stopped

it, I was off heading

because it stopped so

quickly and so cleanly.

Doing the same thing to

the right, I just waited

until my reference showed

up and stomped rudder and

nailed stick forward. It

stopped dead right on the

point. Amazing!

Everything I tried, the

airplane made me look

better than I really was.

Rolling 360s, outside

loops, snaps on the top,

etc., etc. Every single

thing I ask of it, it did

with practically no

technique from me and it

did it cleanly. During my

first snap on the top, for

instance, I popped it

while still a little nose

high like I would in most

airplanes and it completed

the snap before I reached

the top of the loop,

stopping right on heading

and wings level. What a

hoot!

I did have a bunch of

problems with the

airplane, but all of them

were pleasant problems.

For one thing, the nose is

well below the horizon in

level flight, which is a

new experience for a Pitts

pilot. Consequently, I was

constantly pulling the

nose too high and I'd

start at 3,000 feet and

find myself at 6,000 feet

without meaning too.

Secondly, the airplane is

fast, really fast. At 24

inches square it indicates

an accurate 181 mph (it

does the same on a

measured course) and will

touch 200 at full power!

Those are pretty wild

numbers for a biplane!

They are also much higher

than I'm used to seeing,

so I was constantly doing

manoeuvres well below the

proper speed. Finally, I

just stopped worrying

about it, since the

airplane didn't seem to

care how fast it was

going. I did loops as low

as 120 mph and vertical

rolled out of level flight

and flew away.

We'd

had a throttle linkage

problem before takeoff so

the friction lock wasn't

working and the throttle

would creep back, if I

didn't keep pressure on

it. But, that showed me

another side of the

airplane. I'd find I

hadn't watched the

throttle and it had crept

back to 18 inches, but I

was still indicating 160

mph at 4,000 feet!

Every

first flight is nothing

more than a prelude to the

first landing, so my mouth

is always a cotton patch

until the first touch

down. As I came into the

pattern I was a little

fast, about 150 mph, so on

downwind I closed the

throttle completely for a

second. As that big old

81" Hartzell flattened

out, I could feel myself

being thrown into the

straps. The speed was gone

immediately and I made a

metal note to remember

during landing how much

drag the prop adds.

I set

up a downwind with the

runway on the wing tip and

closed the power oppose

the numbers. My intention

was to fly a standard,

power-off 180 degree Pitts

approach, with a belly

check at the 90 degree

point. The guys had told

me to use 90 on short

final and that's what I

had showing. It took less

than a second to realize

the airplane was coming

down a lot faster than

most Pitts and, as the

ground rushed up at me

while curving onto the

centreline, I began to

doubt that it would

flatten out in ground

effect. So, I squeezed on

just a little power and

flew it into the flair.

Just a

little power in this

instance is about twice

what is needed, so I

gradually closed the

throttle and felt for the

ground. Following standard

Pitts practice, I had my

head back as far as

possible, my peripheral

vision working the edges

of the runway. Clunk! The

stiff spring gear and

tailwheel hit at the same

time and I kept my toes

ready to grab brakes and

rudder. My toes were

disappointed, since the

airplane streaked straight

ahead, asking nothing of

me to keep it straight.

How much of that was the

airplane and how much was

the Haigh tailwheel I

don't know, but it sure

was straight.

A

little voice inside my

head shouted, Yee-Haw! The

first landing was over and

the nerve bundles could

relax. This thing was a

pussy cat on the runway!

So, I straightened my left

hand out again and

launched back up into the

pattern, this time clawing

upwards at 110 mph right

from rotation. As I

blasted past the wind

sock, I noticed what I

felt was a creditable

first landing had been

made in a nearly 90

degree, 5-10 knot cross

wind and I had barely

noticed it.

I later

found I could land, climb

back up to 1,000 feet on

downwind and land again

and never get past the

mid-point of a 3,000 foot

runway. Not even on climb

out. What an absolute

blast!

I also

found I could fly power

off approaches okay, but

had to carry an extra 5-10

mph across the fence to

ensure the airplane

flattening out and

floating on ground effect.

And then it floated too

much. At anything under 90

mph power-off, it was

sinking so fast, I don't

think ground effect would

slow its rate of descent

enough to prevent a hard

landing. In most

approaches just enough

power to keep the prop

from flattening out would

probably be wise. And

then, when the power is

killed, the pilot had

better be ready to land

because the prop will kill

any speed he has left.

I'd

have to say that my two

short flights in Super

Stinker were the most

enjoyable and most

informative flights I've

made in the last fifteen

years. They were enjoyable

because the airplane could

do no wrong. Whether I was

aerobating it or landing,

stalling or cruising, it

was just about as nearly

perfect as I thought an

airplane could be. Granted

it may not be the right

mount for a GlassAir

personality which rated

utility above all, but I

could certainly see adding

another ten gallon tank to

Super Stinker and using

her for cross country

work. When we were talking

about what improvements

the airplane needed, about

the only think I could

think to tell Curtis was,

"It needs a different

shaped tail, one that

looks like a Pitts!"

But,

don't think this is a

Citabria pilot's airplane.

It's not. While I think it

is a much easier airplane

to fly than most of the

new aerobatic airplanes,

it still does everything

quite quickly. Including

falling out of the air on

final. An over-grossed

S-2B on a 105 degree day

would be a fair

comparison. It would take

some transition training,

if a pilot had no high

wing loading experience.

The

flights were informative

because they showed that

in any art-form a master's

touch and style is easily

identifiable. It's not

hard, for instance, to

tell a Van Gogh by the

colours and brush stokes.

It's even easier to tell a

Pitts by the feel of the

controls, the balance and

the way it commands the

air. That's what makes the

difference between a

master and a technician.

The master infuses the

work with something

special, something that

gives it texture and color

beyond the norm. And

that's Super Stinker. This

is a very, very special

airplane and it's not by

coincidence that it's

first name is Pitts.

If

plans become available,

the line forms behind me.