The J-3's first

evolutionary step was the J-4 Cub Coupe.

Same airplane, different seating. The two

occupants sat side by side, rather than in

tandem.

The second step

up the passenger-carrying ladder was the J-5

Cruiser. This was Piper's first move into

multi-passenger aircraft. The J-5 was also

the first indication Piper was looking past

the training market at bigger goals.

Let's not kid

ourselves: The J-5 IS a J-3. It's a Cub with

fat hips where the rear seat was widened

out.

An important

change in the fuselage and general layout

was moving the pilot up front and moving the

front seat away from the pedals. Any who

have flown a J-3 in the front remember that

folded-like-a-pocket-knife seating position

and the chest-high control stick. The Piper

engineering crew made an effort to civilize

the front seat by giving it more leg room.

In addition, when widening the back seat and

tapering the fuselage to the firewall, they

couldn't help but give the front seat lots

of shoulder room. In fact, the front seat

clearance may be the widest of any aircraft

of its type, before or since.

The original

J-5A came out in January of 1940 being

pulled along by a 75 hp Continental. A year

later it was replaced by the J-5B which used

the 75 hp Lycoming 0-145, an engine which

has never had a reputation for lots of

power.

In 1942 Piper

made a major jump forward when it announced

the J-5C which was powered by the 100 hp

0-235 Lycoming. Yes, this is the same 0-235

Lycoming (with very minor changes) still

being used in C-152s and, yes, that makes

the basic engine 55 years old! The only

difference is that in the J-5C the engine

was carrying three people not two, as in the

C-152. Sorry, just a little editorializing.

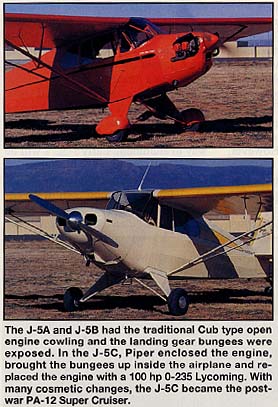

The Charlie

model included some major structural

changes. Among other things the windshield

was now one piece and the wood spars gave

away to aluminium. Early J-5C's will be

found with wood spars because they didn't

complete the change-over until using up all

the wood then in inventory. The landing gear

was redesigned to bring the bungees up

inside the airplane and the engine was

completely cowled for the first time.

The cowling and

landing gear mods amounted to a huge drag

reduction which, when coupled with the

equally dramatic increase in power made the

airplane live up to its name. At 95-100 mph

it truly was a Cruiser. Plus it offered

amenities like a starter and nav lights. An

18 gallon wing tank was standard in all

Cruisers, but another seven or 18 gallons

could be put in the other wing. With the

J-5C Cub Cruiser, Piper had stepped into the

serious cross country market. Unfortunately,

the war shut down Piper's civilian aircraft

production after cranking-out only 35 J-5Cs.

The new design

didn't go to waste, however. The Navy liked

what they saw in the airplane and, with

several of their own mods, including a

top-opening rear fuselage for a litter,

ordered the aircraft as the HE-1. Something

over 100 were produced.

After the war,

the J-5C was re-certified to 1,750 pounds

gross weight (Normal Category) and the 1020

mild steel in the fuselage tubing replaced

with chrome-moly. The new airplane was the

PA-12 Super Cruiser. It was produced for two

years, 1946-'47 and over 3,700 were built.

Approximately 1,400 J-5s were built.

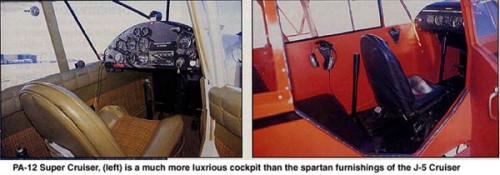

It appears the

Piper marketing department had as much to do

with the design of the PA-12 as engineering

did. In most respects, it's structure was

identical to the J-5C but marketing's

contribution was in taking a noticeable step

away from the stark interior of the

traditional Cub to much more luxurious

appointments. The 1946 market place was

fiercely competitive and they needed to

change their image to survive. Accordingly,

many of the Cub's old control layouts, some

of which were the result of its trainer

role, were changed. For instance the carb

heat was now on the panel, as was the

mixture for the 0-235. The panel itself was

arranged to make room for a radio ($65

installed!). The interior was tastefully

appointed and an effort made to bring it up

to automotive standards of style and

comfort.

It should be

pointed out, however, that the back seat of

either Cruiser isn't really two people wide.

It's more like 1 3/4 people wide since they

have to twist and let their shoulders

slightly over lap. With only one person in

the seat, the extra room is overkill.

Mechanical

Description

As originally

designed, the J-5 Cruiser is a Piper Cub in

every respect and so needs little mechanical

discription. The steel tube fuselage was

widened and that was the only discernable

difference. In fact, most major components,

wings, tail surfaces, landing gear vees, are

interchangeable.

One minor

control change is that the carb heat was

moved from its awkward location by the

pilot's right foot to make it more

convenient by his left hip. The aluminium

cup holding the carb heat and fuel cut off

is unique to the J-5, even though the Cub

has something similar.

The original

brakes were the traditional expander-tube

type which are terribly expensive to rebuild

today because of the cost of the expander

tubes and the individual brake blocks. Many

J-5s are seen with either the hydraulic drum

brakes of the PA-12 or Cleveland/McCauly

disk brakes.

The brake

pedals on both models are of the heel

variety, with those on the PA-12 moved

slightly out board to make them more readily

available. This also puts them slightly in

the way and easy to touch inadvertently on

the first few flights.

The J-5C and

PA-12 landing gears moved the bungees up

inside the airplane, so the bungee struts

and the structure at the front end of the

fuselage is noticeably different.

Other than the

usual fuselage rust concerns, the Cruiser

series also have the Piper strut AD's to be

complied with. The wing ribs are aluminum as

are the later spars.

Flight

Characteristics

Not wanting to

rely on memory, we travelled to Tailwheels

and More in Prescott, Arizona which use a

J-5A in their instruction programme and have

a pristine PA-12 on line for rent. There we

evaluated both airplanes with Allen Steffey,

owner/operator of Tailwheels, acting as

instructor pilot.

Steffy's J-5A

is redone in the colours it carried in 1941

when delivered to Muncie Aviation, where it

served in a CPT school. In speaking with

old-time Muncie instructors, Allen learned

they used the J-5's as night trainers with

motorcycle batteries providing the lighting

power.

The airplane

was wrecked at least three times before

being purchased by a doctor in Bisbee,

Arizona who re-engined it with a C-90. Each

year, the doctor used the airplane to

deliver medical supplies to Panama, which,

according to the logs, took 70 hrs each way!

In the late 1980's the doctor was having the

airplane re-built when he passed away.

Steffy bought the airplane as a nearly

completed project and incorporated it into

his school, which also uses Champs, C-140's

and a Stinson.

The airplane's

bad luck wasn't left behind when it moved up

to Prescott. After Allen took it to Oshkosh

'96, it wound up on its back when, it is

surmised, a passenger surprised a renter

pilot by inadvertently locking the brakes.

Steffey completely rebuilt the airplane,

correcting many of the non-original features

it had picked up over the years. He did not,

however, rebuild the expander tube brakes

because of the expense involved, and

retained the Clevelands.

In climbing

into the cockpit, I was first struck by it's

size, when compared to a Cub. Spacious would

be the best adjective to apply. The rudders

were still just a little closer than I'd

like, but we have to remember this

generation is taller than that for which the

airplane was designed. Even better than the

room, was the over-the-nose visibility.

Straight ahead visibility was only slightly

impaired.

"Mags hot!

Brakes!" One flip of the prop and we were on

our way. The heel brakes were a fair amount

inboard of the rudders which was of no

consequence because they were only needed

for tight manoeuvring during taxi. Also,

even though we had a 20-25 knot wind

battering us during taxi, the tendency to

weathervane was easily controlled with

rudder only. A J-5 is at least 100 pounds

heavier than a J-3 and its ability to ride

out the wind is one place it helps.

The wind was

varying between 30°-60° off our nose on

takeoff and I expected an "interesting"

flight. I wasn't disappointed but I was

surprised at how well the airplane handled

it. The takeoff run had to be partially on

one wheel to keep it straight but the

controls were absolutely up to the task.

Even though the airplane had 90 hp, we were

at 5,000 ft MSL (density altitude around

6,500 ft.), so the power was probably the

equivalent of the original 75 hp

Continental. This gave the wind plenty of

time to work us over during the takeoff

roll. At no time did it feel as if the wind

was about to get the upper hand so long as I

used a firm touch. At lower altitudes, with

that engine, takeoffs happen

instantaneously, with a 150 foot take-off

roll being typical.