The first lines for the new airplane,

the Model 7 Champion, were laid on vellum early in 1944

and the airplane flew in May of that year. Chief test

pilot Louis Wehrung did the honours. The official

designation of the airplane was 7AC (Model 7, first

variation, Champion) and it used the A-65 Continental.

In laying out the configuration of

the Champ, designer Ray Hermes took square aim at his

primary competition, the J-3 Cub, which by that time,

was nearly a decade old. He made a list of every one of

the Cub's shortcomings and designed them out of his new

airplane. The final lines of the Champ are the net

result of Anti-Cub design goals.

Forward visibility had always been a

Cub weak point and Hermes solved that in two ways.

First, he put the pilot in the front seat and, second,

he raised the seating position and dropped the nose so

the pilot could see straight ahead while on the ground.

This is why a Champ appears so high in the cabin, when

compared to the Cub. The Cub may have finer, sleeker

lines, but the Champ pilot can not only see where he's

going but sits up in real comfort (relatively speaking).

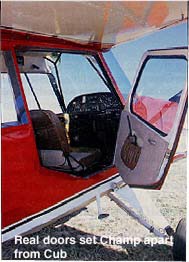

Cubs also came in for criticism in

the drafty arrangement of the door. While the split door

may be perfect for viewing sunsets today, when the Cub

was working for a living, instructors and students alike

cursed the leaky doors. The Champion used a hinged,

single-piece door not unlike an automobile.

A little over 8,100 Champs were

produced, most of which were the 65 hp 7ACs which ended

production in April of 1948 to be replaced by the 85 hp

7BCM (it was fuel injected and had a larger dorsal fin,

as well) which was ordered by the military as the L-16A.

The military then went to 90 hp (fuel injected) and the

nearest civilian counterpart was the 7CCM. The most

common civilian version to come out of all of this was a

combination of the A and B model L-16, the 85 hp 7DC

which had the larger dorsal and an additional fuel tank

in the right wing. Only 166 7DC's were built before the

final Champ was introduced, the 90 hp 7EC. The final

Champ rolled off the Aeronca line in January of 1951. It

was Champ 7EC, SN96, N4749E. Anyone know where it is

today?

A good design has a way of surviving

and the 7EC is one of those. In 1954, Champion Aircraft

of Osceola, Wisconsin, put the 7EC back into production

where it continued to be up-graded, eventually becoming

the 7ECA Citabria in the early 1960's.

Mechanical Description

Champs use the triangular

aft-fuselage Gene Roche originally designed for his

little C-2 in the late 1920s. Because most Champs

have probably spent more time tied down outside than in

hangars, the plywood formers which fair the fuselage

into a square shape have to be considered suspect. Bad

fuselage wood isn't a major safety concern but it takes

time and money to replace it.

Other than being triangular in cross

section, there is little about a Champ's fuselage

structure that presents unique inspection concerns. All

steel tube fuselages share the same corrosion concerns,

especially in the rear of the fuselage and in the strut

carry-through tube under the floor.

The trim system is something else

that the designer worked at to make more efficient than

that on a Cub. When twisting the Cub trim crank, the

stabilizer is being screwed up and down while the

overhead knob in a Champ, which moves fore and aft in a

slot, runs a trim tab on the elevator. The arrangement

is quicker and easier, although, since it is located

over the front pilot's left shoulder in the ceiling,

it's a stretch to reach from the back seat.

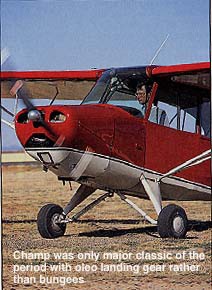

To absorb landing shocks, the Champ

uses an oleo-spring arrangement in the front leg of the

landing gear "V" frame rather than bungees. In speaking

with Buzz Wagner of the International Aeronca

Association, he said the landing gear is the area in

which they see the most problems, mostly because people

don't maintain them or don't understand the system. The

system is designed to use exactly eight and a half

ounces of fluid. Let it get a half an ounce down and the

gear will be damaged. According to Wagner, the majority

of Champs in operation need the landing gear rebuilt to

one degree or another and the difference in ground

handling, when all the worn parts are replaced, is

significant.

There were two different oleo's

installed, the original straight oleo, and the "no

bounce" oleo which came out of the military's desire for

an airplane that could be dropped from ridiculous

heights without damage. The original oleo is less

complicated and easier to handle in a crosswind. Wagner,

among others, has new and rebuilt replacements for

either.

All Champs prior to the 1954

re-introduction of the 7EC used mechanical brakes. These

brakes, if properly adjusted, work just fine. There are

two distinct different types, the Van Sickle/Cleveland

type which is a traditional drum and shoe set up where a

rotating cam actuates them and the Goodyear which is a

form of mechanical disk brake. In neither one is there

no an adjustment to move the shoes or pads closer to the

drums to compensate for wear, as in a car. This is a

weakness in the design and adjusting the cable tighter

(most mechanics' initial urge) won't help. All that does

is rotate the cam closer to its limits. Wagner says, if

shoe brakes are no longer holding, replace the shoes. In

the calliper brakes, replace the pads, and if they still

don't hold, have the cam built back to its original

dimension by welding.

The post-1954 American Champion 7EC's

used hydraulic drum brakes which eliminates most of the

problems. Fortunately, none of the brake types are

expensive to rebuild.

The wings are a combination of wood

spars and formed-aluminium ribs. There is no rib

stitching, as with most fabric airplanes, as the fabric

is screwed or pop-riveted to the ribs. Generally

speaking, Champ wings give little or no trouble.

The wing struts are welded closed

which makes them less susceptible to rust than some

others. Rust, however, is still a definite concern and

they should be carefully inspected as per FAA guide

lines. The end fittings are welded bushings, not

adjustable forks, so there is no concern in that area.

Flight Characteristics

It takes about ten seconds in a

Champ's cockpit to decide that all of Chief Designer

Hermes' Anti-Cub design goals were met and then some.

Some argue the Champ cockpit is too modern. Too

civilized. Those are usually Cub pilots speaking.

Once on board, the immediate

impression will be of visibility and a cheerful

airiness. The wing and skylight is so high and the pilot

sits so far forward, there is none of the "Man trapped

in an airplane" feeling of so many of the Champ's

contemporaries. This is definitely the airplane for a

big person.

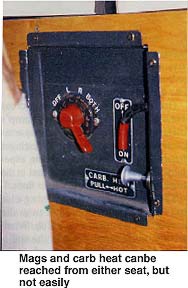

One of the cockpit's niceties is that

all of the major engine controls, i.e. carb heat, fuel

on/off, mags are in a panel by the pilot's left hip.

This makes them available from both seats, although the

front seat pilot has to squirm around a bit to get a

hand down there.

Incidentally, the later airplanes

have most of the fuel in the wings and do away with the

fuselage tank, while the original airplanes have a fuel

gage peeking out of the top of the boot cowl for the

fuselage tank.

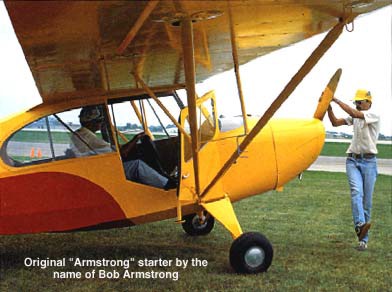

If it's a 7AC, you'll be doing the

"Brakes! Contact!" routine with an Armstrong starter. If

a 7EC, there's a "T' handled on the right half of the

instrument panel that eases the starting chores.

In most areas, there's a big handling

difference between the A and E models because of the

difference in weight. An original, lightly finished A

model with its 65 hp Continental weights about 710-725

pounds or about the same as a Cub. The 90 hp E models

sometimes weigh as much as 200 pounds more because of

electrical, interior, tanks, etc.

There's some difference of opinion as

to how to start a take-off in a Champ, stick forward or

stick back. A lot of the flight schools that used later

7ECs with the No-Bounce gears routinely started the

takeoff roll with the stick full forward. Presumably,

this was done to get the tail up as soon as possible to

keep the oleos from extending. If the pilot waits too

long to pick the tail up, the weight will come off the

oleos while in a three-point position allowing them to

extend. When they're extended, they have little to no

resistance so they'll compress easily. When one

compresses, even though the airplane is headed straight,

the illusion is that the airplane is turning and pilots

often poke in rudder that's not needed causing a swerve

where there was none. Bear in mind, however, that all of

this is happening in slow motion as the airplane will

fly-off somewhere in the neighbourhood of 45 mph.

Theoretically, the bigger engine

Champs will climb better than the lowly 7AC, but not by

much. The books say an AC is supposed to give 500 rpm

and the EC 800 rpm. In real life, the difference isn't

that great. Because of its lighter weight, the 7AC

floats off the ground compared to the 7EC which feels

more like it's on rails. Only the very lightest 7AC,

however, has the feather-like feeling of a Cub when it

separates.

Most of the Cub's resemblance to a

feather is probably because the Cub has just enough more

wing area that its wing loading at gross is a little

lower, 6.8 lb/sq. ft to 7.1 lb/sq. ft. The books say a

7EC weighs 890 pounds empty (1450 pounds gross, more

than a C-140) compared to a 7AC at 710 pounds (1220

pounds gross, about the same as a Cub).

Note that the 7EC, despite its much

bigger engine has about the same useful load as the 7AC.

Once up to cruising speed, the 7AC

(65 hp) can generally be depended on to be 5-8 mph

faster than the similarly powered Cub, or a good solid

85-90 mph. The 7ECs seem to run about 90-95 mph.

Ask any who fly a Champ and they'll

all say its a "...rudder airplane...". That's because

its adverse yaw is so pronounced, you either coordinate

with rudder or slip and slide around on the seat. It's

much more noticeable than in a Cub. This makes it a

superb trainer.

When you start trying to compare

things like roll rate and aileron pressures between

airplanes like Cubs and Champs, you're dealing more with

perceptions than actual differences. For one thing, the

Cub control stick juts up higher, especially in the

front seat, and has an innately "bigger" feel to it. The

mechanical advantage means the stick moves further than

a Champ's in the same situation, but the response is

probably close to being the same. The pressures, also,

are close, but it is very difficult to say. The

perception is that Cub controls are heavier, when they

really aren't.

There is, however, a difference to

the overall "feel" of the controls. Somehow, a Cub feels

a little more precise and a touch quicker. We're

splitting some very slow-speed hairs at this point, but

that seems to be the general opinion.

Compared to a C-152, the roll

performance will seem leisurely at best. The pressures

are slightly lighter than a Citabria and the roll rate

about the same.

The Champ stalls normally, with just

a tiny bit of edge to it. Release the stick and it's

flying again. Kick a rudder hard and it rotates into a

surprisingly comfortable spin that stops as soon as you

release back pressure and punch a rudder. Just letting

go will bring it out almost as quickly as doing

something deliberate.

Depending on the model, a Champ is

happy to approach at just about any speed, but keeping

it under 60 cuts down the float. Three-point landings

happen almost automatically once you get used to a nose

that's not in the way. The sight picture isn't that much

different than landing a C-152 on its mains and holding

the nose off. Actually, you can probably see more out of

the Champ.

In a no-wind situation, the airplane

will track perfectly straight. Given a good cross wind,

the pilot will have to work a little harder but the

airplane will handle it as long as the pilot keeps the

wing down and the nose straight.

Wheel landings are also automatic and

probably easier than in any other type of taildragger.

Just don't force it on. Let it find the ground, pin it

in place and the landing is over.

The controversy between those who

love the Cub and those who swear by the Champ will never

be resolved. The important thing to remember is they are

both terrific airplanes and the Champ wouldn't have

survived as long as it has if it hadn't had the Cub as a

role model.