Every pilot has several images

stored up, which he or she

projects on their mind's eye

from time to time as a way of

remembering a wonderful moment.

The one I replay the most is the

image and feeling of dropping

the hammer on my first Bearcat

takeoff. The acceleration was so

sudden and all-encompassing it

felt as if it was launching me

through some sort of space

continuum and I'd emerge on the

other side a different person.

In fact, I did emerge a

different person. It changed my

way of looking at airplanes

forever.

Every takeoff

since that first Bearcat

experience has been a

comparison, another step in the

search for the same

exhilaration. Until this week,

only one airplane has come even

close, the Grumman F3F/G-32A.

And then I

flew Jim Younkin's Mullicoupe

last week. Now there's another

image to rotate through my

mental theatre with those of the

Bearcat and the F3F. The

Mullicoupe definitely left it's

mark.

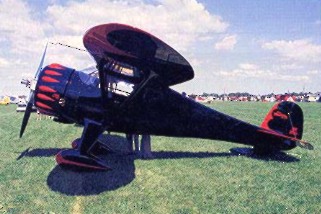

Any who were

at Oshkosh undoubtedly came away

with stories of the two hulking

red and black airplanes that

were "...sorta Monocoupes and

sorta Howards." A spectator

didn't have to know what the

airplanes were to know they had

just seen magnificent examples

of the airplane builder's art.

If they hung around long enough

to pick up the specifics, they'd

realize those were Bud Dake's

and Jim Younkin's Mullicoupes,

just two more in a long, long

line of nearly unbelievable

flying machines to bear

Younkin's unique touch.

It's probably

redundant to once again explain,

or try to explain, Jim Younkin

who operates Historic Aviation

in Springdale, Arkansas, as he's

regularly mentioned in these

pages. However, it is very

necessary to point out that he

is far more than simply a

builder, or a designer or a

creative thinker, even though in

each of those categories, he may

well stand at, or near, the head

of the class. Younkin's

combination of talents may well

make him unique in our field.

There are a number of others who

can free form aluminium nearly

as well. There are others who

are adept at designing and

engineering. There are numerous

shops out there that build and

restore airplanes as well. There

are very few, however, who, like

Jim, combine it all.

Quite often,

when an individual has the above

kinds of characteristics, he is

likely to be selfish with what

he knows. Just the opposite is

true with Younkin. Walk in his

shop with a question and he's

likely to drop what he's doing,

step over to the trip hammer or

English wheel and show you how

it's done. He's almost zealous

in his urge to get knowledge and

understanding about what he's

doing out to other people. His

much-modified Piper Pacer is a

classic case in point: It's hard

to imagine how many other Pacer

owners have borrowed ideas from

Jim's airplane, most with his

help. It's probably the most

copied airplane of its type

ever, although he often doesn't

receive credit for some of the

mods.

Jim is

blessed with the intellect and

the skills that are required to

take any idea and make it a

reality. For that reason, when

he starts musing about a

particular restoration project

or new design, it's a good idea

to sit up and take notice. Jim

Younkin's day dreams almost

always become reality. That's

exactly how the Mullicoupes came

to be.

Actually,

Younkin blames Bud Dake, he of

the familiar menacing black

Clipwing Monocoupe and central

figure in the on-going Creve

Couere aerodrama, for the

Mullicoupes coming to be.

Younkin had

taken Mr. Mulligan, his 600 hp

recreation of the golden age

racer, to the antique fly-in at

Blakesburg for the first time

("...I didn't really plan on

landing, as it was way too

short, but there the runway was,

so..."). Towering over so many

of the other antiques, it was

the center of attention. The

year was 1982. He and Bud Dake

were sitting in the shade

admiring the airplane's lines

that afternoon when, according

to Younkin, Dake said something

to the effect of, "...you know

what we really need is a 450 hp,

two seat version of Mulligan

just for personal

transportation..." Younkin

agreed.

As Younkin

remembers it, they talked about

it for a couple of days at the

fly-in, deciding such an

airplane should borrow heavily

on the lines of the Monocoupe.

Jim says that's when the name "Mullicoupe"

came into being.

When Younkin

came home he started doodling.

Jim Younkin, however, doesn't

doodle like the rest of us. His

doodles have numbers and

dimensions attached. So, in

another year or two a totally

accurate scale model of the

airplane took shape in Younkin's

shop. He had the concept. He had

the dimensions, so he did the

next natural thing and started

cutting metal.

At that point

he was building a single

airplane for himself, but it

wasn't long before Bud Dake and

Red Lerille, another Monocoupe

fanatic, had jumped on board.

So, when Jim built a component

for his airplane, he'd build one

for theirs as well.

For a number

of years the Mullicoupe was a

"fill-in" project as Younkin's

shop was completely immersed in

a Staggerwing Beech assembly

line. At one time he had four

Staggerwings lined up, each

receiving massive amounts of

restoration, modifications and

aluminium work.

Finally,

several years ago, the

Staggerwings were finished to

the point they were ready to be

delivered to the owners, and the

Mullicoupe project really got

serious.

As quickly as

Younkin would finish a

component, it would be shipped

to Dake and Lerille and the race

was on to see who would fly

first. Dake won.

On the first

flight, they discovered the

airplanes needed much larger

vertical fins. The tiny surface

which was desired to maintain

the Monocoupe look just wasn't

large enough. Younkin produced

larger surfaces for his and

Lerille's airplanes, but Dake,

true to his nature, was

beginning to like an airplane

that had little or no airborne

directional stability so he

hasn't modified his.

The final

airplanes are a little daunting

both in presence and in

specifications. From a distance,

it would be easy to mistake them

for D-145 Monocoupes. As the

distance is closed, however,

they grow in size until it's

realized they are very serious

airplanes. The lines start with

the flawless bumped aluminum

cowls wrapped tightly around a

fuel injected P & W R-985. The

lines flow back with more

Monocoupe than Mulligan in them

until they wasp-waist their way

down to the tiny tails. The

wings are very much Mulligan in

both line and execution.#

The 29'3"

wings look short for the

dense-looking fuselage and in

fact are short: The wing loading

goes from 24 to 27 pounds/square

foot, depending on how much of

the 150 gallon gas tanks are

filled. Even with the 22 gph

fuel burn of the Pratt and

Whitney, that gives a solid (and

impressive) 7 hours of range at

a high altitude cruise speed of

225 mph.

I was more

than just a little apprehensive

as I backed up to the door to

hoist myself up into the cockpit

(the door jam is nearly chest

high). The airplane has a

pugnacious presence about it

that just sitting on the ground

says "fly me if you can." Bobby

Younkin, Jim's son and the well

known airshow pilot of both a

Twin Beech and Samson, scrambled

into the other seat to help make

the introductions.

Once inside

the airplane, the extreme deck

angle, 15°, was clearly evident.

The cockpit slanted downhill

much steeper than any airplane

I'd ever flown. This was going

to be a challenge.

When the

engine cranked, it caught on

only the second or third blade

laying down the wonderfully

classic opening movement of

Symphony de Round Motore.

The airplane

doesn't have a steerable

tailwheel, so most ground

handling is done with brakes. I

had only a short, five foot wide

stripe of the side of the

taxiway visible at an extreme

down angle, so I was at first a

little overly cautious. I found

quickly, however, that the nose

tapered fast enough that by

leaning against the side of the

cockpit, I could actually see a

fair distance ahead and only a

slight S-turn was necessary to

clear the taxiway ahead.

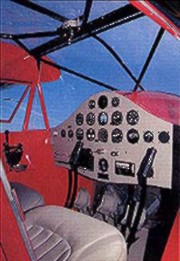

The cockpit

has an open cheery feel to it

because of the sky light but the

feeling is also helped by the

antiquey, vaguely triangular

instrument panel. If the panel

hadn't been scooped out at the

sides and had a round top like

most instrument panels, the

visibility to the quartering

sides would have been abysmal.

As it was, I had a clear view at

an angle of about 40° (a guess)

off the nose.

As I glanced

around the cockpit I again

remembered Younkin's description

of the fuel system. The tank

selector is between the seats,

along with the push-pull

tailwheel lock. What is not

visible is the float and vent

system in the header tank.

R-985's with fuel injection,

rather than the usual carburetor,

take a frighteningly long time

to restart once you've run a

tank dry. Sometimes the silence

lasts as long as 20 seconds.

Younkin's fix for that is a low

fuel warning light in the header

tank that lets you know you've

only got a few gallons left

before the pilot light goes out.

At the same time, the float

activates a servo which opens a

direct vent into the header tank

so, when you switch tanks, it

will fill faster. If, for some

reason, the servo doesn't

activate, there's a tiny spigot

over the co-pilot's head that

manually opens the vent for

faster filling.

As we rolled

out and centred ourselves on the

runway, I could see it was going

to be a real challenge to

actually get the airplane into

three point position on landing.

At that point, I didn't know

exactly how much of a challenge

it would be.

I also didn't

know how exhilarating the

takeoff would be. At our weight,

the power loading was down

around 5.2 pounds per horsepower

which is about on a par with the

lighter aerobatic specials. But

that number doesn't take into

account the effect of having

nearly 1000 cubic inches feeding

that big prop.

I fixated on

the furthest point where the

edge of the runway hit the nose

and started easing the power in.

The airplane responded by

instantly leaping forward. When

I saw the airplane wasn't going

to go darting off one way or the

other, I finished putting the

rest of the power in and hung

on. I was just in the process of

picking up the tail when the

airplane got light on its feet

and I was slow to react to the

message. The result was we

didn't separate cleanly and I

let a slight crosswind push us a

little.

Gheez! I was

thinking. Gimme a break. I

hadn't caught up with the

airplane yet and it was ready to

takeoff long before I was.

I glanced at

the airspeed as we left the

ground and was amazed! We were

rocketing through 110 mph and I

had just barely gotten full

power in.

I brought the

power back to climb settings

immediately and held what I knew

was a fairly shallow climb

angle. This seemed a smart thing

to do around an airport. It was

obvious the Mullicoupe would

sustain any nose angle I wanted,

but I'd be blind as a bat in a

bucket. With everything all

squared up, I again checked the

airspeed. We were indicating 160

mph on a very hot, humid day but

the VSI was showing 1800 fpm!

How's that for a cruise climb,

sports fans?

Through out the entire takeoff

and climb out, the world didn't

exist out the other side of the

airplane. The width of the

cockpit and the bulk of the nose

conspired to shut that part of

the world out of my view. As the

nose came down, the view

improved dramatically, but the

very top of the cowling was

still slightly over the horizon

and it was hard to see out the

other side. That, however, is

just the way old airplane are

and, as far as the Mullicoupe

crew is concerned, what they

have built is a new, old

airplane.

The concept

from the very beginning was that

they would take up where Benny

Howard had left off with the

Mulligan and do it they way they

would have done it in those

days. As we rumbled across

Arkansas at 5,000 feet and

205-210 mph TAS, it looked to me

as if Benny would be proud to

have his name associated with

the Mullicoupe.

Jim told me

Bud Dake had conducted

exhaustive tests at 11,000 and

determined the airplane's best

cruise speed was indeed 225 mph

at 22 gph. This is only 5 mph

slower than the Mulligan after

which it was patterned. Younkin

also said the airplane really

needs a 12:1 blower drive rather

than the stock 10:1 which would

make it much more efficient at

higher altitudes.

The controls

are much better than any

Monocoupe I've ever flown.

Actually, they are better than

any Howard's (with the possible

exception of Mr. Mulligan).

There is no way to describe them

other than they are "normal."

The break-out force around

neutral is just about right and

the aileron pressure goes up

slightly with displacement

(positive gradient). The

response is better than a modern

Cessna and on a par with a new

Beechcraft.

Rudder is

extremely powerful and it took a

while to get my feet toned down

so I wasn't slamming the ball

around. Younkin has a locking

bar for the rudder which locks

it straight ahead for cruise

which adds it's area to the fin

thereby making the airplane more

directionally stable in cruise.

I brought the

power back and started setting

up for a clean stall. I was

doing fine until we got down to

around 110 (we'd been indicating

around 195 mph). Then the

airplane didn't want to slow

down any more and I was out of

trim. I keep pulling, the VSI

kept going down, and eventually

we started shedding excess

speed, but it was a struggle.

Finally, down in the low 80 mph

range, the stick came against

the stop where I held it to see

what would happen. The airplane

mushed ahead and nothing

happened.

Then I

started playing with the flaps.

The flaps are another Younkin

original and are beautiful the

way they work. They are true

Fowlers, but he's been able to

keep the entire track within the

wings surface. They track back 5

1/2" before they go down more

than a few degrees. He considers

half flap to be about 10° or so.

That amount of movement takes up

about 80% of the track length.

The final percentage of travel

cranks them down 30° quite

quickly.

The flap

controls are two switches. One

is a traditional three position

momentary switch that can be

used to select any flap

position. It can be paired with

a second switch marked "1/2" and

"full." With that switch in the

"1/2" position, slapping the

power switch all the way down

gives only half flaps. Then,

when you're ready, you can just

push the position switch down to

"full" and that's what you get.

They hadn't

finalized their flap speeds when

we flew the airplane but they

were using 110 mph for half

flaps and 100 mph for full.

Getting slow enough to get full

flaps was the biggest challenge

of the flight. Half flaps gives

almost no drag and the airplane

doesn't want to slow down. Also,

we were nearly out of trim at

that point so stick pressures

were building. As soon as the

rest of the flaps went out,

however, all was right with the

world and the airplane was

perfectly willing to sit at 100

mph with very little help from

me.

I had

expected the full-flap stalls to

be much more pronounced, but

even tugging the stick into my

lap and holding it there

produced little more than a

bobbing mush in the low 70's

mph. As the airfoil is the tried

and true 23012, I'd expected a

sharper break. We didn't

investigate accelerated stalls

which I suspect may have been

sharper.

I let Bobby

shoot the first landing, which

was a tail-low wheely. I made

the second approach with no

intent of actually landing. I

just wanted to get the feel of

the airplane in approach, so I

flew it into ground effect and

added just enough power to keep

us skipping along the ground

after a brief touchdown while I

tried to develop some

references. Throughout approach,

the runway was clearly in view

but it disappeared the second

the nose was brought up. If a

person isn't used to flying

blind airplanes, this airplane

is going to be something of a

shock. However, the side of the

runway is clearly visible

because of the way the

windshield wraps so far down the

side of the fuselage.

On my next

approach, I resolved to try for

a three-point. I wrestled it

down to 100 mph, got the flaps

out and made a curving intercept

with centerline. Runway

disappears behind the nose as I

begin pulling and then pulling

some more. Then I felt the mains

touch long, long before I was

ready for them, so I nailed it

on in a wheel landing. It

probably looked okay from the

outside, but it wasn't what I

wanted.

With it's

running on the mains, only a

little more of the runway is

visible, but it is so well

behaved it doesn't make any

difference. The tail came down

and the airplane still tracked

straight. No sweat. Power up

more firmly this time. I was

beginning to get comfortable and

was enjoying the takeoffs. What

a blast!

Okay, I was

telling myself. Next time

around, I'm getting the

three-point position and nailing

it on. Curving approach, good

speed, good position. I spot the

side of the runway and start

trying to hold it off. Ground

effect wasn't helping me much so

I was working hard at rotating

fast.

I wasn't fast

enough. As I was pulling and we

were in what I thought was a

three-point attitude, we

ricocheted off the mains, this

time leading into a healthy

skip. It was one of those,"...do

I or don't I add power?",

marginal situations. I opted not

to add power. That was a

mistake. As the airplane started

back down, I increased the back

pressure only to find the stick

was already against the stop.

The mains touched and bounced,

then the tailwheel touched and

bounced. Then the mains came

down again, then the tailwheel.

I've got the stick nailed to my

belly and all I can do is sit

back and watch a spectacularly

ugly crow hop landing.

The good news

was that at no time did the

airplane want to do anything but

roll straight ahead, nor did it

unload and actually drop us

hard. The only bad result was

severe embarrassment for me. If

I'd just touched the power on

the first hop we'd have been

okay. After that, it was too

late.

By the time

I'd taxied back to the hangar,

I'd thought about the entire

process enough and was ready to

go at it again. This is an

airplane I'd really enjoy

getting good in. Not to mention

the adrenaline rush every time

the throttle went in.

The three

Mullicoupes now flying are

likely to be the only ones ever

to be flying. Although Younkin

has been approached by several

people wanting him to build

components for them, he hasn't

decided he really wants to do

that.

The

Mullicoupe is definitely not

everyone's airplane. But for

those drawn to nostalgia and who

love round motors and serious

performance, this could very

well be the answer to a dream.

Who knows? Maybe Jim will relent

and open the doors to others

wanting a taste of Howard's

legacy as interpreted by Jim

Younkin. If not, at least the

rest of us can admire them from

the sidelines.

A

Short Hop With Mr. Mulligan:

When Benny Howard designed and

built Mr. Mulligan in the late

1930's there would be no way he

could have imagined it being

replicated 60 years after the

fact. When Jim Younkin arrived

at Oshkosh with his near-perfect

replica it blew minds right and

left.

When Younkin,

Bud Dake and Red Lirille decided

to build the Mullicoupes it was

with the goal of building a

better Mr. Mulligan in smaller

scale. So, when Jim offered me

the chance to fly Mulligan, I

felt it was important to my

scientific research that I force

myself to take the time to

accept his invitation. Yeah,

right! I'd wanted to fly the

airplane since the first time I

saw it. Besides, it really was

important I sample what had set

the Mullicoupes in motion.

Both Dake and

Younkin have said they feel as

if they fell short of their goal

to better the Mulligan.

On the first

takeoff, the first thing I

noticed was how much better I

could see out of the Mulligan.

Better, however is a relative

term as most people would still

think it blind as a post hole.

Also, I had

no trouble saying up with the

airplane and getting it solidly

on its mains before it caught me

unawares. That may be because

I'd just stepped out of the

Mullicoupe or because the

airplane, with a wing loading in

the mid 30 pounds per square

foot range, so was solid.

In terms of

pure performance, the Mullicoupe

appears to have the edge in

climb but the Mulligan is much

faster at low altitudes. We were

indicating 205 mph (230 mph TAS)

where the Mullicoupe was showing

190-195 mph. Of course the

Mulligan was also burning 33

gallons as opposed to the

Mullicoupe's 22 gph.

Where I did

notice the difference was the

control feel. The Mulligan's

ailerons are much quicker and

smoother. In fact, they were

flat-out lovely. The rudder,

however, was one of the most

sensitive I've ever touched.

In cruise the

Mulligan was a solid as a brick

building, a feeling that

continued right down into

approach. With full flaps and

100 mph showing, the airplane

was dead simply to gently hold

off before putting it on the

mains. Once down, it was solidly

down with no tendency to hop or

porpoise. Some people have ask

whether it was like landing a

Howard DGA-15P, which it

resembles and the answer is an

unequivocal no. The Mulligan's

gear is much stiffer and the

airplane's easier to land. Any

similarity to a DGA-15 is

strictly cosmetic, as the

Mulligan's character is so much

more refined and precise.

After flying

the Mullicoupe, when you hear

Dake and Younkin express

negatives about the airplanes,

you have to think they're out of

their collective minds. After

you've flown Mr. Mulligan, you

begin to understand where

they're coming from.

The

Mullicoupe is a helluva

airplane. Mr. Mulligan is the

daddy of that airplane and it

shows.