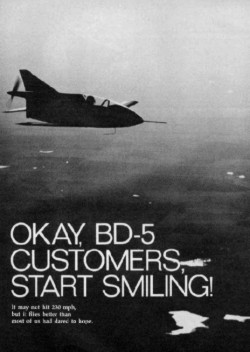

the BD-5 Actually Flies

by Budd Davisson, courtesy of

www.airbum.com

Okay all

you skeptics out there (and I was one

of the strongest), let it be known

here and not that, not only does the

BD-5 fly, but about 90 per cent of us

owe Jim Bede a gigantic apology. He

has managed to build a tiny little

wing stability platform that shows

more thought ingenuity and out and out

genius than anything general aviation

has seen for years.

It still has some bugs to iron out in

the engine department but, other wise,

the BD-5 , as we flew it, represents

the first quantum leap forward in

light aircraft design since WWII. As I

was hoisting my fanny up out of the

little cockpit after flying it, all I

could think of was, "Jim Bede, I'm

sorry for all those rotten things I

said about you and your airplane."

He's made a believer out of me.

You have to be a yak-herder in the

Himalaya boonies not to know the saga

of the BD-5 by heart. Every magazine

with a circulation of more than 15 has

run at least one story about the BD-5

and it's rotund, hyperactive

designer-builder-promoter, Jim Bede,

and therein may lie one of the

original seeds of the great Bede

controversy, as it now rages. Too much

was said too early in the game,

promises were made, performance

figures quoted and money taken. So,

when things didn't go like clockwork,

the BD buying public got a little bit

ticked off. (Witness the lynch mobs

lurking in dark corners at Oshkosh,

lying in wait for him.)

There is no doubt that many early Bede

claims were optimistic. No they were

more than optimistic, they were

outlandish (270 mph was promised t one

point).

I sat in the bleachers with the rest

of the aviation community and watched

the whole Bede experience develop. I

booed and hissed right along with the

others. I can clearly remember

receiving a three-view of the very

early Micro and my first impression

was that Jim Bede was absolutely and

irrevocably out of his tree. The

entire thing just wasn't possible. All

of us sidewalk engineers gawked at the

early V-tailed fibreglass prototype

and nodded knowingly. It was generally

agreed that, if it did fly, it would

have the inherent stability of a bongo

board and the handling characteristics

of a Whiffle ball.

After a while the old "it will never

fly" crowd changed their tune to "it

may fly but only a NASA test pilot can

handle it," You see, had to find

something else to gripe about because

that chainsaw with wings was flitting

around at far too many airshows for us

to maintain credibility in the face of

fact. It did fly and appeared to fly

well.

Naturally, there is only one way to

find out if "Joe average pilot" can

fly it and that is to snuggle down

into it and go aviating, so we asked,

"Can we fly your airplane?" The answer

was, "of course." First Bede had to

check a few things out. Next month

maybe. When it was next month, the

answer was in a few weeks, then it

went back up to months. This went on

for over two years. It looked like a

classic holding action against a press

that might leak the news that the BD-5

was nothing more than a cylindrical

coffin with retractable handles.

At Oshkosh the word came down: we

could come down to Newton and fly his

airplane at our convenience. At our

convenience, really? We didn't begin

getting excited until we called him

and he said, "Sure, how about

tomorrow?"

The second I stepped off the plane at

Wichita, I knew it was trouble. It was

blowing about 35 knots in the middle

of the night. They were probably

chaining the cattle to the ground. The

next morning Les Bervin, BD test

pilot, confirmed our suspicions and

allowed as how it wasn't the best day

to be flying the BD-5 for the first

time, but it was okay to fly the BD-5T

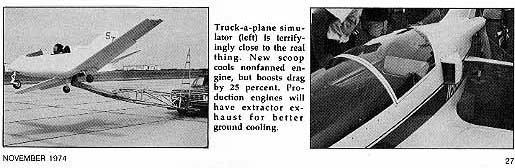

trainer. There two-ton Tinker-Toy

trainer is almost as ingenious as the

BD-5 itself. Using a systems of

springs and booms, they have hung a

clapped-out BD-5 (early victim of a

journey through a ditch) on the front

bumper of a Dodge pick-up truck. The

springs counterbalance the weight of

the boom almost exactly, so any lift

generated by those ridiculous little

wing panels will life it off the

ground and let you shoot

touch-and-goes and make gentle turns

to your heart's content.

Looking at the truck, the airframe and

the rail-straight windsock, I

suggested we draw straws. I lost. The

other two guys locked themselves in

the truck cab, leaving me to be the

first to find out what a Dodge-powered

BD-5 was like. Rich strapped me into

the trainer and explained rotations

speeds and offered a few helpful hints

as he was putting the headset down

over my twitching ears.

My first flight in the trainer was

sort of hop, jiggle, bounce, scrub. I

over-corrected, over-rotated and

over-wound just about everything. the

side stick initially seemed incredibly

sensitive, then, magically, about half

way down the runway things seemed to

smooth out. The second run had me

hopping off the ground like a frog on

a hot rock, but by concentrating on

the runway in front of me and

forgetting where my hand was resting,

I could even keep the wing down and

cancel out the crosswind, which by

this time was a solid 40 knots. The

third time around I rotated off almost

like a normal airplane. I was flying

big gentle S-turns all the way down

the runway while I called out my

height to Rich in the cab to see how

close I was. The fourth run was

unnecessary; I felt like I knew what I

was doing. The rest of the guys had

very nearly the same reaction.

What the BD-Dodge

combination showed me was, first of

all, takeoff happens very quickly and

it is easy to over-rotate. then it was

even easier to over-rotate the

rotation, which caused a little bit of

saw-toothed flight for a while. the

most important thing I learned was

that by focusing my eyes straight

ahead and flying it like one of those

fly-by-wire games in the bus depot, I

could eliminate most of my

over-controlling difficulties. It is

strictly a visual affair because there

is absolutely no fell or pressure in

the control stick. We each had a

chance to look through the flight

manual, but Les sat us all down and

went methodically down the list so

each of us knew what to do when.

Besides all the usual numbers, there

were a few things I found even more

important to remember. The first was,

if the engine quit, we couldn't

restart it. This particular bird had

the starter ring gear removed and they

had to fire it up with a pull-cord.

Also, the clutch and the drive system

is such that the prop freewheels when

the engine isn't running. Even though

the prop is turning, the engine isn't.

that didn't sound too bad, but then he

mentioned that if we touched zero G

for even a second, the float-type

carburettor they had temporarily

installed would choke the engine

deader than a mackerel. well, if

nothing else, I realized that kind of

information would make me tiptoe

around while doing aerobatics.

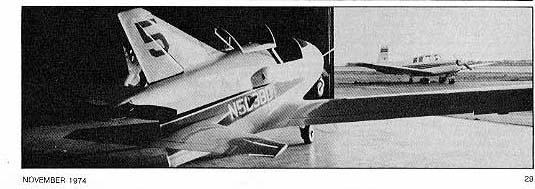

There aren't a whole lot of airplanes

around in which you can actually

retract the landing gear while sitting

on the ground for cockpit check, but

then, there aren't too many airplanes

six guys can pick up and put on

sawhorses either. That is where we sat

while familiarizing ourselves with the

cockpit. From the instant I

stiff-legged myself down into the

cavern underneath the panel I was

knocked out by the logic of the

cockpit. Everything is in the right

place, easy to use and figure out. The

fuel controls are ahead of the left

console and all the electrical stuff-mags,

master, etc.- on the right one. the

landing gear is a healthy looking

T-handle affair that would look more

at home in a jacked-up GTO. It juts up

between your legs about where the

control stick should be and the flap

handle is right next to it. The

control stick is shaped like a Baby

Ruth you had squeezed in your hand,

and sticks up out the right console.

Only the trim, which is right next to

the throttle, and the stick appear or

feel anything but perfectly placed.

Once up on the sawhorses, we amused

ourselves with the landing gear. It

takes a healthy tug to get it started

up, but more than the, you have to

keep it moving so the inertia of the

gear helps to get the handle over

center. If you don't keep your

shoulder behind it, it will stop

halfway and you'll never get it up.

When you pull and keep on pulling, you

are rewarded (or surprised) with a

healthy whack on the bottom of the

fuselage. There is absolutely no doubt

that the hear is up or down. When it

slams into position, the airplane

practically jumps off of the

sawhorses. It's like being inside of a

giant switchblade. Les had us do it

without moving the stick so we

wouldn't be jumping around in the air

when retracting the gear. it was good

practice, but it didn't work.

we figured the way to beat the wind

was to get up before it did, which

still didn't work. At 5:30 the next

morning, with my eyes clamped shut to

keep my precious bodily fluids from

leaking out, I staggered to the door

to see that it was still blowing up a

mini-storm outside. We thought we'd

had it, but Les stuck a finger into

the breeze and said, "Roll it out;

let's go flying." A few minutes later

I found myself fiddling with chokes,

mixtures and mags and hopping over

expansion joints in the taxiway as I

wended my way down to the runway. In

taxiing, the engine idled at nearly

3000 rpm; it sounded like a lawnmower

trying to run me down. I pressed the

transmit button on the top of the

throttle and said, "I'm ready to go."

My headphones answered, '"Good-bye."

Looking back at it, I'll have to admit

to not remembering much about that

take-off because it all happened so

quickly. The engine revved to about

5000 rpm immediately and the 52 hp

behind me started kicking me down the

runway at an astonishing rate. At 50

mph I started picking up the nosewheel,

which skipped a couple of times; as I

rocketed to 60-65 I was up and away.

The take-off was almost toy-like. I

bobbed around a bit, more from

surprise than from anything else. As

soon as I started watching what I was

doing and got out of ground turbulence

at 10 feet, it settled and felt almost

as solid as a Cessna 150 would have in

the same wind. At around 75-80 I

reached down for the landing gear,

completely forgetting the keep-on-pullin'

retraction technique. I gave it a

cursory jerk. As the handle came to a

halt in the midway position, I called

myself a few choice names and rammed

it forward to lock it down again.

While I was busy jamming the gear

handle, I forgot where my right hand

was and unconsciously tweaked the

stick. This caused the airplane to

jump around. When I gave the gear a

healthy pull it obediently leaped into

the wells. As the gear came up and I

let the flaps up slowly, the speed

wrapped up to 1-- mph pronto.

The best-rate-of-climb speed was 90

mph, but I was keeping it at around

100 for cooling. We climber 1200 feet

per minute with 52 hp blatting away

behind, the tack working its way up to

6500 rpm and the 182 camera plane

disappearing fast.

The most surprising thing about those

first few minutes of flight is that

everything seemed so normal. I didn't

even bother to look out at those

tooth-pick wings or marvel at the

incredible visibility. It just felt

that was the way airplanes should be

this was an airplane and it just flew

like one. I wanted it to feel strange

and exotic, but things fit together

too well.

Set your hand on the chair next to you

right now and make a list. Now wiggle

it left-to-right while keeping your

elbow stuck to the chair. If you don't

move the top of our fist more than

half an inch or so, you'll see what it

is like to fly a BD-5. there is no

noticeable resistance and practically

no movement of the stick. If you

twitch your hand an inch to the side,

you've just done a roll. Move it an

inch or so back and you loop. Now,

that sounds like it's sensitive, but

for some reason or another it doesn't

work out that way. It's got to be the

most natural way to shepherd an

airplane around I have ever seen.

Les had sworn that the stalls were

nothing to write books about and he

was right. In any configuration it

would shake, buffet, leap and groan as

you crept up to the stall, One wing

would unload as it would roll off in

one direction of the other. I'd keep

the stick completely back and porpoise

ahead, using aileron and rudder to

keep everything square with the world.

the instant-I mean the very

instant-the elevator was released, the

little beastie would be flying again.

Clean it was stalling at about 65, and

dirty at about 55.

I cursed the zero-G carburettor as I

sucked the nose up and tweaked my hand

left to watch the sky and ground swap

places. With just a little inverted

capability-just a couple of

seconds-you could drag the rolls out

into long, sensuous affairs over which

you'd have infinite control. I'll have

to wangle another flight when they put

the new carburettor on, I guess. you

can roll fast or your can roll slow,

four points or eight, left or right,

and barely move your hand. To the

right, rolls are just a little more

difficult, because your wrist works

more naturally inboard than it does

outboard. Full aileron deflection is

only about a 2-inch twist of your

wrist, but you almost never need it.

The roll rate is fast, about 150

degrees per second, which is just a

tad slower than a roundwing Pitts. I

can't begin to describe the total

precision of these controls. They

don't even come close to being

sensitive, but they put more control

in the palm of your hand than any

other airplane I know.

Now, almost nobody reading this is

going to believe my next statement,

yet it's absolutely true: the BD-5 is

one of the most stable little

airplanes flying. When I'd set it up

hands-off and then pulse the

stick-just bash it forward or back-the

nose would come up and then-bam-come

back to level and not move again.

There was almost no sign of

oscillations of any kind. The same if

true of yaw: punch and rudder, and the

nose snaps back as soon as you let go.

In roll it seems just a little more

neutral. The wings stay pretty much

where you put them. I tested all this

stability out by grooving around for a

while as I used both hands to adjust

my headset and boom mike, to eliminate

some communications problems (which

turned out to be my inability to read

"volume" one the radio face).

The BD-5's high thrust line means a

nose-down pitch with poser. (the nose

comes up when you back off the

throttle). Speed and power changes do

give a fair amount of trim change, but

I had been flying for a while before I

noticed that I had been unconsciously

moving the trim control with the thumb

of my throttle hand all along.

I knew Bede had done complete spin

tests, and Les had told us to go ahead

and spin it. But I'll admit that I put

spins off until I worked up my nerve.

Finally, I got the power back, got the

stick back, and kicked rudder as it

stalled. Instantaneously it snapped

over on its back and twisted downward

into a near-vertical spin. the first

turn was more of a snap roll, the

second turn was very oscillatory, with

the nose coming up fairly high. They

the nose dropped to about 60 degrees

and stabilized in a very fast spin.

Sixty degrees, by the way, looks like

you're going straight down. Les had

said that the airplane had a distinct

stick-free spin mode, here the reduced

drag of neutralize controls caused the

speed to increase and the spin to wrap

up very tight. That's why it needs a

classic NACA spin recovery: bash the

stick well forward and nail opposite

rudder hard.

Naturally, I managed to botch up the

recovery. I moved the stick forward

too slowly at the end of three turns,

and it immediately cracked around in

two more lightning-fast turns before I

got the stick far enough forward. I

recovered in less than half a turn,

going absolutely straight down. I

instinctively loaded a slight positive

G on it to keep that carburettor

happy, and, in so doing, got a slight

secondary spin in the other direction.

But that topped almost immediately.

the second time I spun it, I did what

Les had told me to do, and it popped

out instantly. It's a very

predictable-spinning airplane, but you

have to move like you mean business to

stop it where you want it.

On the way back into the pattern, I

made a couple of speed runs at 5,000

feet AGL. (9,000 feet density altitude

for that day). I was showing an even

155 mph cruise, and that works out to

177. Later, Peter did the same thing

down lower, at 1,000 feet, and got a

solid 175 mph indicated, which works

out to 188.

I knew I couldn't stay up all day and

avoid the landing. I flew a wide

360-degree overhead pattern, coming

downwind at 100 mph and base at 90. It

had taken me forever to get into the

pattern, because power off, at 85 mph,

I was only showing about 380 fpm

descent. I was beginning to wonder

about getting down before lunch. Les

had said the gear worked like

spoilers, and when I dropped it, I saw

what he meant. With gear and flaps

down I had to use just a tad of power

to fight the wind as I turned final

for the taxiway we were using the

land. (It was smoother than the

runway.)

The pitch stability came in handy for

holding 85 right on the money as I

jockeyed the power just a little to

stay on glide path. I kept reminding

myself what the view over the nose in

the trainer had looked like as I came

closer to the ground. the wind tried

to boggle me around but a tweak here

and a tweak there kept everything

perfectly lined up. As the pavement

started to get closer, I gently (very

gently) started to flare. The second I

moved the nose, the airplane stopped

coming down. So, I relaxed a bit and

started feeling for the ground. Lower.

Lower. Lower. Suddenly I knew I was

only a foot or so off and I started a

game with the wind. I tried to hold it

up as the wind stared to bat me

around. Plunk, and the mains were on.

I tried to hold the nose hear up, but

the flaps were too much for it and it

dropped onto the pavement anyway. We

were on the ground at around 60 mph.

The roll out was easy to control with

the rudder and I didn't need to use

the brake at all until I was ready to

turn into the parking area.

Well, I think we've discovered what

kind of pilot it takes to fly the

BD-5. Any proficient 150-hour pilot

could learn to handle it, but only if

he had already developed certain

skills and mental attitudes. He'd

better be an accurate pilot. He can't

make vague, unmetered control

movements or be only fuzzily aware of

what he sees over the nose. The

airplane is capable of absolute

precision, and to make consistently

smooth landings and takeoffs, the

pilot must use that precision. Most

pilots are sloppy; they'll have to

de-slop themselves before the fly the

Five. the guy who takes great pride in

making nothing but squeakers right on

the centreline won't have any trouble

at all. This type of mental attitude

is totally independent of flight time,

and can be present or absent

regardless of how fat the logbook may

be.

Flying the trainer would be the best

bet for transitioning into the Bede.

There you get the super-low ground

attitude, seating position, and

control response all in one package.

Otherwise a glider-especially

something like a Blanik or a 1-34-will

give you a perfect learning situation

for the supine seat and ground-hugging

landing attitude. an older Yankee

would give you the basic control

responses-the brake-only directional

control, and similar stall

characteristics., (the BD-5's are far

better.)

Asked how I feel about it, I can only

say that now I wish I hadn't let my

scepticism keep me from putting down

my $400 deposit for a production

model. Oh, well . . . Bede probably

has something else up his sleeve, and

you can bet I'll put my money where my

doubts are this time.

|