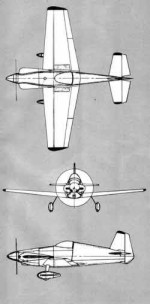

Midget Mustang

by Budd Davisson, courtesy of

www.airbum.com

Reflections on a

Two-Time Grand Champion

I was feeling anxious as

I looked out at those

chrome-like wings and

down that mirror

straight cowling. I

wasn't worried much

about being able to fly

the airplane, but the

awful responsibility of

actually flying an

airplane that's too

pretty to face the

vagaries of flight at

strange hands was

getting to me. This

craft was the Grand

Champion Homebuilt at

Oshkosh for two years

running. Its lines and

metal work were only

supposed to appear in

artists' renderings.

Lloyd "Jim" Butler's

retractable gear,

folding wing Midget

Mustang was something

else ... something that

nearly defied

description. At that

point, sitting there in

front of that

machine-turned panel

with the tiny stick in

my hand and the

Plexiglas bubble doing

its best to enclose my

boggled mind, I wasn't

absolutely certain I had

the guts to fly this

machine. But, let's be

realistic, I wasn't

about to turn down the

chance either.

My hand moved forward

clenching the throttle

and the 100-hp

Continental responded

with more pep than it

ever had in a C-150. My

visibility over the nose

was restricted, and I

had to stretch my neck

to get the the canopy

combing down out of my

peripheral vision for a

clear view of the edges

of the rapidly moving

runway. 1 didn't even

try to lift the tail. I

let it come up when it

was ready and then held

a tail low position; my

feet applying slight

pressure on the right

rudder to keep from

turning left. Then came

the fear and

apprehension in

remembering to reach up

and throw the magic

switch that made the

wheels disappear behind

those clam-tight doors

in the belly.

As the gear cycled up, a

finely machined round

spool on the floor ahead

of the stick rapidly

rotated 360 degrees, and

I reached down to force

the lever on its top

behind a pin, thereby

locking the gear

securely up. I was up

and I was gone.

Responsibility be

damned, I already loved

the airplane.

Jim Butler has got to be

one of the most trusting

people in the entire

world. I was number

seven to fly his

airplane; an airplane

that represents six

years of his life. He

had built an

award-winner before, in

the mid-'60s, and it too

had been a Midget

Mustang; that 1948 sport

plane design turned

non-competitive formula

one design and back to

sport plane. That one

had been built according

to the plans, more or

less, but the second one

was entirely different

and took advantage of

his skills as a sheet

metal worker and

machinist in the form of

lightened structure,

retractable gear and

folding wings.

A walk-around on his

airplane is a lesson in

old time metal working.

The cowl cheeks, for

instance, were hammered

free-form out of sheets

of aluminium, an art

that has just about

disappeared outside the

walls of artisan

sanctuaries such as the

Ferrari plant. Every

panel is butt-jointed

and the edges match like

adjacent grain lines in

clean spruce. Each rivet

is countersunk and

seated with such care

that a fingernail,

should you have the

nerve to run one across

the skin, wouldn't catch

on a single edge. And,

of course, it's all

hanging out there in

front of God and

everybody because rather

than hiding anything

behind a coat of paint,

he polished it bright; a

move only the most

confident of craftsmen

could make.

Turning out of the

pattern, I suddenly felt

intense heat on the side

of my head and I jerked

around half expecting to

see flame swirling down

one side of the

fuselage. Instead, my

eyes were stabbed by the

white-hot reflection of

the sun on a wing panel.

One of the problems, I

found in flying with a

large mirror on either

side of you, is that you

can expect to get fried

if you hold certain

headings for any length

of time.

The altimeter was

winding up tight. At

something over 1200 fpm,

I was upstairs in no

time. I began, not with

a turn or a stall, but

with a four-point

aileron exercise, then

another, with twice the

number of pauses. The

break-out forces of the

controls were next to

nothing, but the stick

movement ratios were

such that a little stick

movement gave a little

roll rate. But when you

wanted to see the world

go by in an absolute

blur all you had to do

was try, just try, to

get full aileron. Those

finely shaped little

wing panels streak

around faster than you

can move your hand.

Even though your head

sticks out of the

fuselage in a tiny

pimple of a canopy, the

visibility and comfort

are amazing. I'm certain

Butler's RG Mustang

shares this with all

others of the more

conventional Midget

Mustangs. The nose drops

down in level flight to

give a shimmering view

of polished panels and

the effect is one of

flying in a very nose

down attitude. The floor

is nearly flat, so your

feet stick out in front

of you MG fashion with

an armrest console on

either side. The gear

switch is in the left

vertical console and the

flap handle (three

notches to forty

degrees) is under your

left arm.

Nose down, I got 180 mph

indicated and gently

sucked the nose up into

a loop. Up, up vertical

and then, as the nose

approached the inverted

position, the airplane

let me know I'd been

heavy handed by

unceremoniously doing a

half-snap into a right

side up position ... I

had stalled it. I looked

around to see if anybody

had seen my foul-up (I

could always claim it

was an intentional

Immelmann), and tried

again. The second try

was just as

embarrassing.

Eventually, I found it

took hardly any stick

pressure to loop. Just

pull the nose up and let

it find its own way over

the top. It knows how

much G it wants on the

top and it will do it

all by itself, with no

help or hindrance from

the guy at the controls.

Enough. It was time to

work, so I got the carb

heat and slowed down for

a stall. First of all,

slowing down isn't easy.

It's like trying to get

a rifle slug to shed

speed. Holding a nose

high attitude, I watched

the needle wind its way

slowly towards the

bottom. Finally, at

about 60 mph IAS, with

almost no buffet at all,

the wing said it had had

enough and quit flying

all at once. It was very

much as you'd expect

from this type of

airplane, a wing

dropping, sharp-edged

stall, with a very quick

recovery. I have a

hunch, if you were to

cross control very much

during a stall, it would

probably snap into a

spin with little or no

wavering.

I bent and twisted,

pushed and pulled until

I started to feel guilty

and began to think about

giving the man his

airplane back. But,

wait, I can't just

blithely hum along in

this thing without

finding out for sure how

fast it is. I'd been

looking at indicated

airspeeds of 160 mph

plus all the time that I

was in it, but we all

know what liars airspeed

indicators are. So, up

into a 45-degree bank,

power off, pulling hard,

I screwed my way down to

1000 feet AGL to go

looking for some easily

identifiable check

points. Four times I ran

two-way distances, and

four times I came up

with a speed of 160 mph

2400 rpm. I have to

admit I was a little

disappointed, although

that still works out to

about 27 miles per

gallon. Bob Bushby the

biggest fan and promoter

of the Midget Mustang

says the usual 100-hp

Mustang should cruise at

about 190 mph. Butler's

airplane doesn't seem to

have the proper

propeller pitch for best

cruising. Also, it's

carrying around about 70

pounds of extra weight

with the retractable

gear and other Butler

modifications. In the

Pazmany efficiency run,

Butler topped out at

just about 200 mph, but

he must have been

winding it a whole lot

tighter than I was.

Basically, it'll go

about as fast as you

want to go, depending on

how much fuel you want

to burn.

Then came landing time

and suddenly, I was

scared again. I mean,

you don't often hurt an

airplane unless you hit

the ground with it.

Downwind, I unlocked the

gear, hit the switch and

heaved a sigh of relief

when I saw the "down and

locked" light go on. One

worry behind me. With

two notches of flap (I

still hadn't touched the

trim since I first took

off), I set up 90 mph

and turned base trying

to gauge my height. I

looked high from the

very beginning so I

hadn't been carrying any

power at all since

downwind, but when it

came time to turn final,

it was obvious I was

still high. This all

came as a surprise

because I expected it to

come down much, much

faster. I didn't want to

embarass myself by

having to go around, so

I gingerly (I'd

forgotten to ask him

about them) began to

slip. Nothing unusual

happened, so I slid as

far into a slip as it

would go. It ran out of

rudder almost

immediately and I came

down final with one foot

on the floor and the

nose only slightly to

one side. Even flying

sideways it had a very,

very flat glide angle.

It's a clean machine!

I remembered the ground

attitude on takeoff as

being extremely flat so

I floated down to about

five feet and added just

a little power to hold

the attitude I wanted.

As I squeezed the power

off, it settled down and

took care of the landing

all by itself. Because

of the direct linkage to

the tail wheel (no

springs) there's no

delay at all to rudder

pedal inputs. I wasn't

actually stepping on a

pedal as much as 1 was

pressuring them one way

or the other in an

attempt to stay on the

white line while rolling

out. And does it ever

roll! It's so clean that

it just doesn't want to

stop running, even on

the ground, and I know

for a fact I had no more

than 65 mph on

touchdown.

I feel as if I've

started at the top and

now have to work my way

down. I had never even

sat in a Midget Mustang

before and now the only

one I've banged around

in is the champ. I have

no idea how

representative it is of

the breed, but I can't

believe it handles a

heck of a lot

differently. Butler, who

has lots of time in both

types of the little

birds, says the

difference is mostly in

the way his builds up

and maintains speed,

which would be expected

with the retractable

gear.

The original Midget

Mustang, as designed by

Dave Long for racing,

was, and is, a nearly

perfect sport airplane.

Its all-metal

construction has been

thoroughly engineered

and tested throughout

the years. Currently the

plans are available from

Bob Bushby of Busby

Aircraft, Inc., Minooka,

Illinois. As an educated

guess, there have

probably been between 50

and 75 of them built

using everything from

the original 85-hp

Continental it was

designed for up to a few

super-exotic jobs with

better than 200 hp. All

of them cruise in the

160-190 mph range. The

nice thing about Midget

Mustangs is that there

are about a trillion of

them being built and you

can usually find

somebody who's got one

partly finished you can

look at. As metal

airplane's go, it's

neither easy nor hard to

build (no airplane is

easy) and aluminium

hasn't inflated any more

than steel tubing and

fabric ... they're all

out of sight now.

There have been at least

two other RG Mustangs

built besides Butler's

that I know of, but they

were all done by guys

like Butler ...

near-pros. If I were

building one, I'd

probably opt for the old

fashioned leaf spring

gear, simply because I

wouldn't want to get

mixed up in designing a

gear and the wing

modifications needed to

house it. One thing is

certain though, it sure

is a pretty airplane

with the wheels tucked

up.

It's almost axiomatic

that when the EAA or

anybody else declares

anything the champion,

there are going to be a

lot of folks bent out of

shape and full of sour

grapes. But, when Jim

Butler's airplane was

picked, there was nary a

gripe heard across the

land. There is no way

pictures can do it

justice, so someday stop

by Norwalk, Ohio, and

ask to see the "shiny

little airplane" and

somebody will point you

at Jim Butler. Then,

you'll see why nobody

disputed it being the

'73, '74 Grand National

Champion Homebuilt.

You'll also see why I

was a bit afraid to fly

it.

specifications

Stock MM-1 Midget

Mustang (not retract)

|

Performance |

C-90 |

125 Lyc |

|

Top Speed |

210 mph |

225 mph |

|

Cruise Speed

|

200 mph |

215 |

|

Stall Speed |

57 mph |

60 mph |

|

Rate of Climb |

1600 fpm |

2200 fpm |

|

Takeoff |

500 ft |

400 ft |

|

50 ft obstacle |

850 ft |

700 ft |

|

WEIGHTS |

|

|

|

Empty Weigh |

540 Ibs |

580 Ibs |

|

Gross Weight |

850 Ibs |

900 Ibs |

|

Wing Loading |

12.5 Ibs/sq ft |

13.2 Ibs/sq ft |

|

Power Loading |

10.0 Ibs/hp |

7.2 Ibs/hp |

|

Fuel Capacity |

15 gal |

15 gal |

|

DIMENSIONS |

|

|

|

Wingspan

|

18 ft 6 in |

|

|

Length

|

16 ft 5 in |

|

|

Height |

4 ft 6 in |

|

|

Wing Area |

68 sq ft |

|

|